The talented Mr. Ripley’s light and shadow or reincarnation of Dostoyevsky’s character

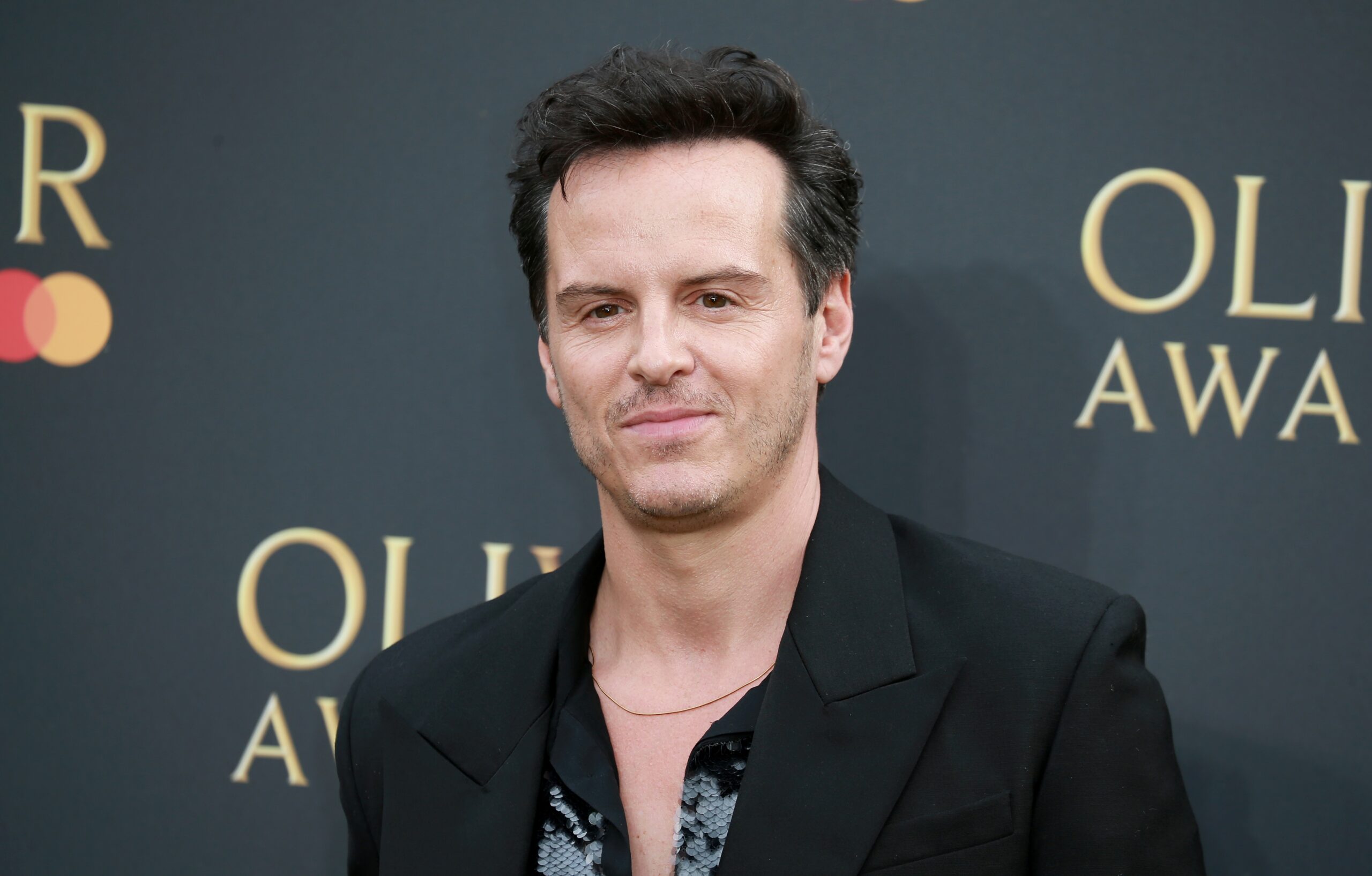

The long-awaited new adaptation of “The Talented Mr. Ripley” with Andrew Scott was released on Netflix. It’s been 25 years since the previous film, 25 years and a whole lifetime.

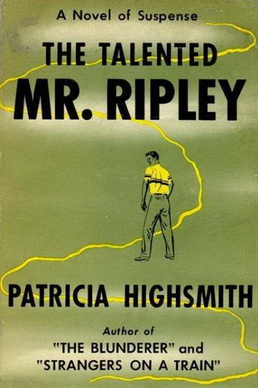

The very first adaptation of the novel was the French “Plein Soleil” with Alain Delon and Maurice Ronet released as “Purple Noon” in the US in 1960. René Clément, director of the film, was accused of “excessive use of actor magnetism and deviation from the novel” (Le Monde newspaper). Patricia Highsmith considered the Purple Noon “very beautiful to the eye and interesting for the intellect”, but she was truly disappointed with the ending:

It was a terrible concession to so-called public morality that the criminal had to be caught”.

Patricia Highsmith

The 1999 film is “the most beautiful thriller”, picturesque, sparkling with triumph and colours. Young and beautiful Matt Damon, Jude Law, Gwyneth Paltrow, and Cate Blanchett are starring. The official title to the movie is “The Innocent Mysterious Yearning Secretive Sad Lonely Troubled Confused Loving Musical Gifted Intelligent Beautiful Tender Sensitive Haunted Passionate Talented Mr. Ripley”. Leonardo DiCaprio was initially supposed to play Mr. Ripley. I wonder if he regrets not being in this film. But Matt Damon got the role and turned it into a moment of glory. Equally star-making was Dickie Greenleaf’s role “for the preternaturally talented English actor Jude Law. Beyond being devastatingly good-looking, Mr. Law gives Dickie the manic, teasing powers of manipulation that make him ardently courted by every man or woman he knows”.

But this story began in 1955 when the first novel in a series of novels about Tom Ripley by Patricia Highsmith was published. Associated with the noir genre, the novel received the Edgar Allan Poe Award, and is one of the top 100 detective novels of all time.

The new “Ripley” adaptation turned out as noir as the novel – black and white, desperately beautiful, bold and slow, tender and passionate, and exceedingly scary. Venice, Andrew Scott, and Shostakovich’s Jazz Suite No. 2 will break your heart.

Black-and-white New York, black-and-white Rome, black-and-white water. And light. Light seen from beneath the sea. “Light,” says the priest, looking at Caravaggio, “Sempre la luce. Always the light.” Yes, light and shadow are the main characters of this series.

Tom Ripley idolizes possessions in the novel:

“He loved possessions, not masses of them, but a select few that he did not part with. They gave a man self-respect. Not ostentation but quality, and the love that cherished the quality. Possessions reminded him that he existed, and made him enjoy his existence. It was as simple as that. And wasn’t that worth something? He existed. Not many people in the world knew how to, even if they had the money. It really didn’t take money, masses of money, it took a certain security.”

What is this story about? About the desire to possess? The tragedy of a little ordinary man? The eternal confrontation of money and its absence, the discrepancy between lifestyles, the unattainable difference between excess and deficiency:

Tom realised he was seeing them on a typical day–a siesta after the late lunch, probably, then the sail in Dickie’s boat at sundown. Then aperitifs at one of the cafes on the beach. They were enjoying a perfectly ordinary day, as if he did not exist”

Patricia Highsmith “The Talented Mr. Ripley”

In this passage, Ripley reincarnates as Ganya Ivolgin (character of the Idiot novel, he is considered “social-climbing petty bureaucrat”) to whom Prince Myshkin essentially denies what he desires most:

I confess I had a poor opinion of you at first, but I have been so joyfully surprised about you just now; it’s a good lesson for me. I shall never judge again without a thorough trial. I see now that you are riot only not a blackguard, but are not even quite spoiled. I see that you are quite an ordinary man, not original in the least degree, but rather weak.”

“The Idiot” by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Or is this a story about something deeper, psychopathic, about the incomprehensible connection between a killer and a victim, as stated by an art historian in front of Caravaggio’s painting “David with the Head of Goliath” in the series? This connection is further complicated by the fact that according to one version, the painting may be a double self-portrait where the young Caravaggio (David) holds the head of an adult Caravaggio(Goliath).

And our hero, the hero played by Andrew Scott, whom we blindly wish to escape persecution, turns out to be much more fortunate than the hero of The Talented Mr. Ripley of 1999. He is slipping away, dissolving into the shadows of Piazza San Marco. Mischief managed? or Is fatal mischief managed?