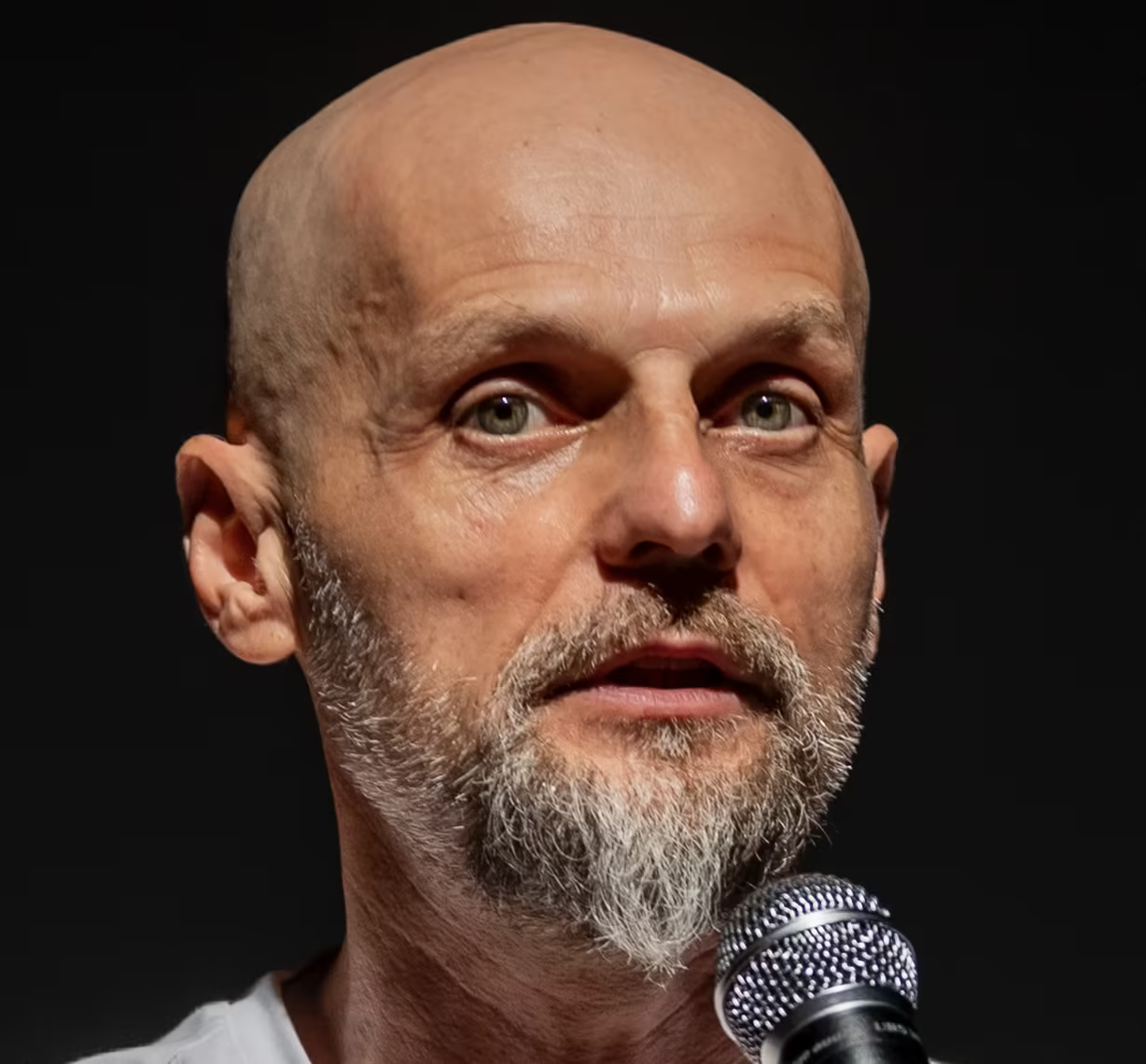

Ivan Vyrypaev: “I Believe in My Mission”

Ivan Vyrypaev is a playwright, director, actor, and teacher. He headed the “Praktika” theater and was one of Russia’s most sought-after playwrights. Today, he writes, directs, and runs the “Teal House” Integral Development Fund in Poland, which he created with his wife, actress Karolina Gruszka. Over the past three years, the fund has helped numerous actors forced to relocate to Europe.

On February 21 and 22, the Marylebone Theatre will host performances of Vyrypaev’s unique project, Mahamaya Electronic Devices. This is a collaboration between Teal House and Bird and Carrot Production, led by Alexandrina Markvo. Mahamaya is a deeply conceptual spectacle, a meditation-performance exploring language and the word—their possibilities (and, consequently, limitations) through the lens of human sensations and intellectual-philosophical pursuits. The emotional depth of the audience’s experience is also due to the fact that Mahamaya is entirely accessible to anyone, regardless of their life experience, origin, language, or education.

As a practicing yogi and thinker, Vyrypaev has shaped the mission of his fund around a unique philosophy: every project aims for development on all levels—physical, intellectual, and spiritual. This is why our conversation with Ivan focused on the recent history of theater, its modern state, and how theater responds to the challenges of our time.

At the beginning of our meeting, when mentioning cigarettes and your smoking habit, you said, “I’m from the old world.” Do you really feel that way?

I was referring to my smoking habit. All my teachers at the Shchukin Theater School smoked. I’ve been trying to quit my whole life, but when I write—which I’ve been doing for almost thirty years—I smoke. It’s a writer’s habit. There was a period when I didn’t smoke, but it wasn’t a very good time for me. In general, I’m a person from the old world, from old traditions, who unexpectedly found himself in the future. I live in the future, using some old habits from the past.

You recently said somewhere that we need to let go of old traditions…

No, never from traditions! I definitely didn’t say that. We need to develop them—and that’s what I’m doing.

When you write a play, does it have to be tied to the present? To the here and now?

Absolutely, absolutely. Drama is a very everyday thing. I am, perhaps, one of the few practicing playwrights today, and I live partly off royalties from my plays—I truly make a living from it. Naturally, I get commissioned to write plays. And, of course, they’re tied not just to a city but to the theater stage. I visit the theater, observe the audience—how they react and to what. My job is essentially to serve the audience. There are plays that transcend this utilitarianism and remain timeless, like those of Chekhov or Molière.

In my view, Molière is the greatest and still unsurpassed playwright. He wrote plays primarily for a specific stage and audience.

Molière was first and foremost relevant to his time—harsh, inconvenient. Today, we read Molière, and no one takes offense at him, but in the 17th century, his plays were almost always banned. Today, I’m working on a Molière play for a French theater. I want modern French audiences to feel what audiences in Molière’s time felt—laughter, discomfort, outrage, and fear simultaneously. But when the theater management asks me to remove sharp elements for fear of backlash from the aggressive liberal-left community, I understand: this is Molière. He was feared and “canceled.” Modern France today is even stricter, with censorship stronger than in the time of Louis XIV. Political correctness, cancel culture, fear—these are the main components of French culture today. And not just French culture. This is why the nation needs Molière again. So they can ban and fight against him, but also love and desire him. To laugh heartily and enjoy classic comedy.

But I still have to compromise. I do it to continue the tradition of the great playwrights who were my teachers, among whom Molière holds the highest place.

How do you handle this?

I believe in my mission. I want to preserve the great dramatic tradition rooted in the understanding that a play is an independent, authentic, literary work meant to be performed on stage. A play is a formula—a score, a set of notes. A play is a performance. A true playwright writes performances. A play begins when an actor opens their mouth on stage—that’s when the play is born.

One of the landmark plays of the early 2000s was undoubtedly your Oxygen. Twenty years have passed—does the play still resonate as it did then?

Right now, in Athens, an up-and-coming Greek director, George Koutlis, has created a grand production of the play at the Onassis Stegi venue, which seats a thousand people. I’m going to see it in January. I immediately thought I should review the text to avoid backlash. I adjusted some things—there were parts that needed rewriting since it was written in 2002, and life was completely different then.

But look—these young people chose the play themselves. That means it works! Oxygen was very popular in Europe, especially in France and Germany. However, I don’t think they’ll return to the play anytime soon—perhaps never. Listen, it features two Russian characters, one of whom is a thug who kills people with a shovel. How could that be staged in Europe today? A play about a Russian shovel? As a producer, I wouldn’t take on such a play now. I wouldn’t even empathize with that Sanya character as an audience member.

But twenty years ago, it was a completely different time—we were all still friends. There was a certain romanticism, with the release of TV series like Brigada and films like Bumer. Back then, Sanya was a trendy hero. Today, I’d feel sick at the sight of a Russian guy with a shovel. Those Sanyas are committing crimes in Ukraine now. So staging Oxygen is a big question.

But it’s just twenty years—so little time!

So little, yet so much has happened, especially in the past three years.

Have you lost many friends along the way?

Almost all of them—those who didn’t leave. But I’ve been connecting with the younger generation a lot. Many young people from Russia write to me—it’s very sad and melancholic correspondence. They gather in apartments and read my plays. They ask, “We’re doing a reading of your play, Ivan Alexandrovich, is that okay?” Of course, it’s very touching, and I tell them I’d be delighted. So, there’s this connection with such people, even though we’ve never met.

But as for my old friends there? I think we’ll part ways for good. There’s a chasm between us now, even though we’ve never quarreled, and I don’t judge anyone. It’s just that we’re like strangers now. I feel that those who stayed will have to make significant adjustments because otherwise, they won’t survive. To live there and earn a living, they’ll have to stop speaking, and to stop speaking, they’ll have to stop thinking.

There’s a saying: “In the house of the hanged, one does not speak of rope.”

In the house of the hanged, one avoids the topic out of respect and reverence for the deceased. But here, people don’t speak out of fear, don’t they? I fear we are irreversibly divided.

When you learned about the criminal case against you, were you scared?

I wasn’t scared, but it was very unpleasant. I was teaching a yoga class and read the news about myself two minutes before it started. I was already seated in front of the class when an actress attending the session told me, “Do you know what they’re writing about you?” But I carried on with the class—it lasted an hour and a half.

It’s unpleasant because there are now many countries I can’t travel to. India, for instance, is a very important place for me—I practice yoga but can’t go there. Or I have to be cautious about flight routes and layovers. Say I’m flying to Georgia, and there’s bad weather, so the plane lands in Abkhazia—that’s it, I won’t make it home.

But on the other hand, what’s there to complain about? Here we are in London, while my friends in Russia are sitting in prison.

Do you remember February 24, 2022?

I remember it very well. I was on tour in the city of Lublin with a Polish production of my play Sunny Line. For forty minutes, I assured the actors there wouldn’t be a war—I completely convinced them. And then my wife called me at five in the morning… I was on my way home and kept calling Ukrainians—all my friends. I had a premiere scheduled at the Drama and Comedy Theater on the Left Bank of the Dnipro.

At the start of the war, I had four plays running in Kyiv and thirty-five performances across Ukraine, and we were all friends. I called everyone… None of us could believe it. Even now, I can’t believe it.

Does yoga help you cope?

Of course, if it weren’t for my practice, I would’ve gone insane. I have an enormous workload, especially with the Teal House fund. People’s lives are difficult, and on top of that, I constantly have to look for funding. I’m not very skilled at that—I’m an artist, after all.

But no one asked us if we wanted this. It just so happened that my life suddenly filled with people who needed help. Ukrainian and Belarusian artists knew only me in Poland. And somehow, we all survived together—sitting, drinking, crying. Then we started helping them get residence permits, which require monthly salaries. Otherwise, their permits would be revoked. I turned into a beggar. For the past two years, I’ve been constantly asking for money. Yesterday I asked for money, and today I plan to ask for money again. I even went to America to raise funds, performing for entrepreneurs, reading my plays. We also win grants.

We’re getting back on our feet—our group is made up of amazing people, children, and there’s a motivating atmosphere. But no one has time to rest. My team is starting to break down: the workload before Christmas was immense, with two premieres and two competitions.

What does an artist need to change in themselves to handle financial matters?

No, this should be handled by knowledgeable people—I’m not the right person for it. I’d like to focus on other things. We have an interesting integral program, with plenty that others could benefit from. For instance, we directly address the challenge of integrating non-native speakers into their environment, and it’s a much bigger problem than I thought. Honestly, even I haven’t fully integrated—I only recently realized that, despite living in Poland for a long time.

I haven’t become a Western playwright. I’m still staged as a Russian author who’s interesting to the West. For example, many of my plays were performed in Germany. But in the last two years, there hasn’t been a single production. I think the context has changed due to the war—perhaps they now need a Russian who writes about the war. But I don’t have plays about the war.

Of course, my new play, The Cherry Man, is imbued with the war. But I can’t just mention Donbas, Kyiv, or rockets. I respect those who do, but I can’t write directly about the war, especially while it’s happening. I believe it’s not necessary to talk about something you lack distance from. I’m more interested in exploring what happens to a person’s soul during such a terrible time, and for that, it’s better to place them in a fictional scenario.