The history of British industry is rich not only in achievements but also in tragedies. Behind the facades of the factories and plants that fed the empire and propelled it into the future lie the fates of those who paid an unbearably high price for progress. Today, these structures have either been demolished, abandoned, or repurposed as museums and art spaces, but the memory of harsh working conditions and deadly hazards of the past still lingers.

Britain’s Industrial Boom: When Death Was Part of the Job

A Factory on the Banks of the Thames

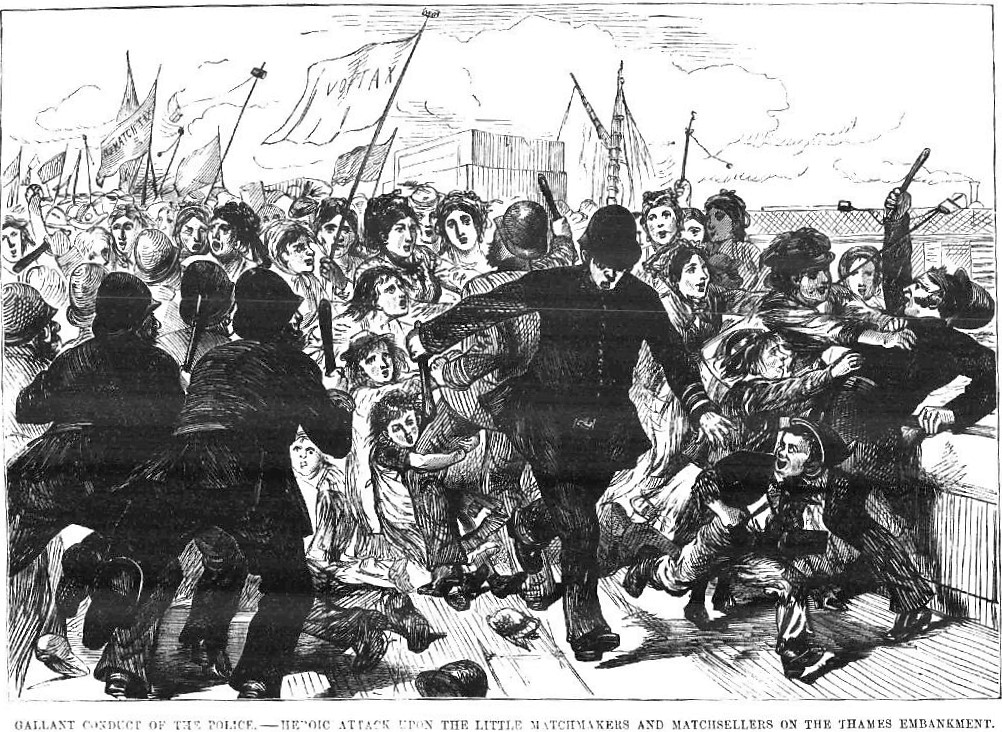

Nineteenth-century London was a city suffocating in coal smoke and toxic chemical fumes. Along the Thames stood textile and leather factories where women and children worked in appalling conditions. One of the most infamous sites was a phosphorus match factory, where workers suffered from the horrifying condition known as “phossy jaw.” Caused by exposure to white phosphorus, the disease ate away at the bones of the face, leading to festering wounds, unbearable pain, and social isolation — the grim cost of survival.

The inhumane conditions at the match factory eventually led to a large-scale strike in 1888, involving all 1,400 female workers. The protest was supported by theosophist and feminist Annie Besant and playwright Bernard Shaw. Initially, factory management refused to negotiate, but widespread public outcry forced them to relent. The workers’ demands were met, including the abolition of unfair fines, the establishment of direct communication between factory workers and management (bypassing intermediaries), and the creation of designated dining areas where toxic white phosphorus would not contaminate food.

The Industrial Hell of Shropshire

Today, Shropshire is associated with rolling green hills and historic towns like Shrewsbury, but in the 18th and 19th centuries, it was a key industrial hub — the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution. The county was home to major ironworks, notorious for their brutal treatment of workers. Machines operated around the clock, producing such deafening noise that many workers lost their hearing at a young age. The damp conditions inside the factories contributed to the spread of disease, while hard labor often led to serious accidents.

In 1833, Britain passed the Factory Act, which sought to limit child labor. Under this law, children aged 9 to 13 could work no more than 8 hours a day, while those aged 13 to 18 were restricted to 12-hour shifts. However, these regulations were frequently ignored, especially in major industrial cities where the demand for cheap labor remained high.

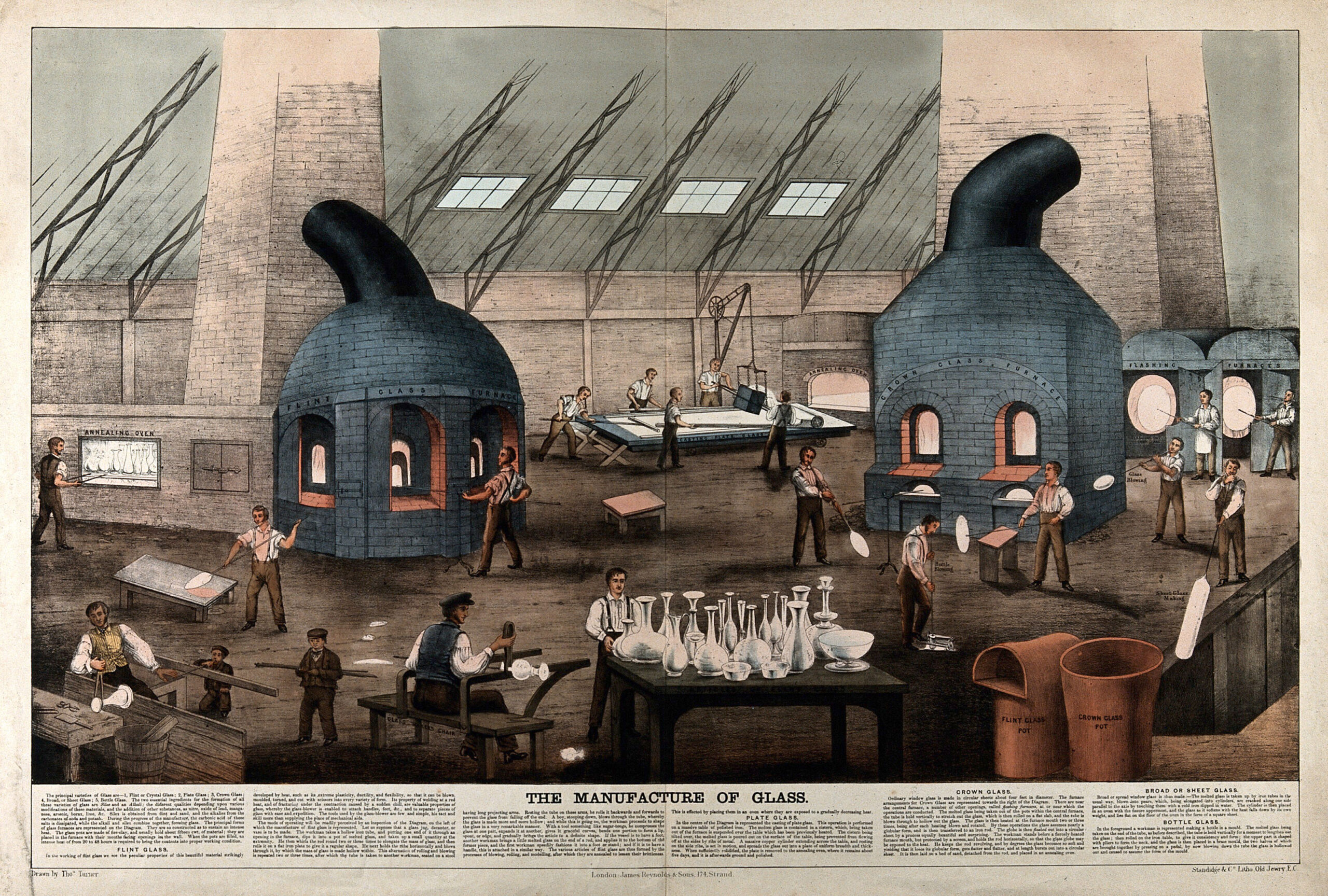

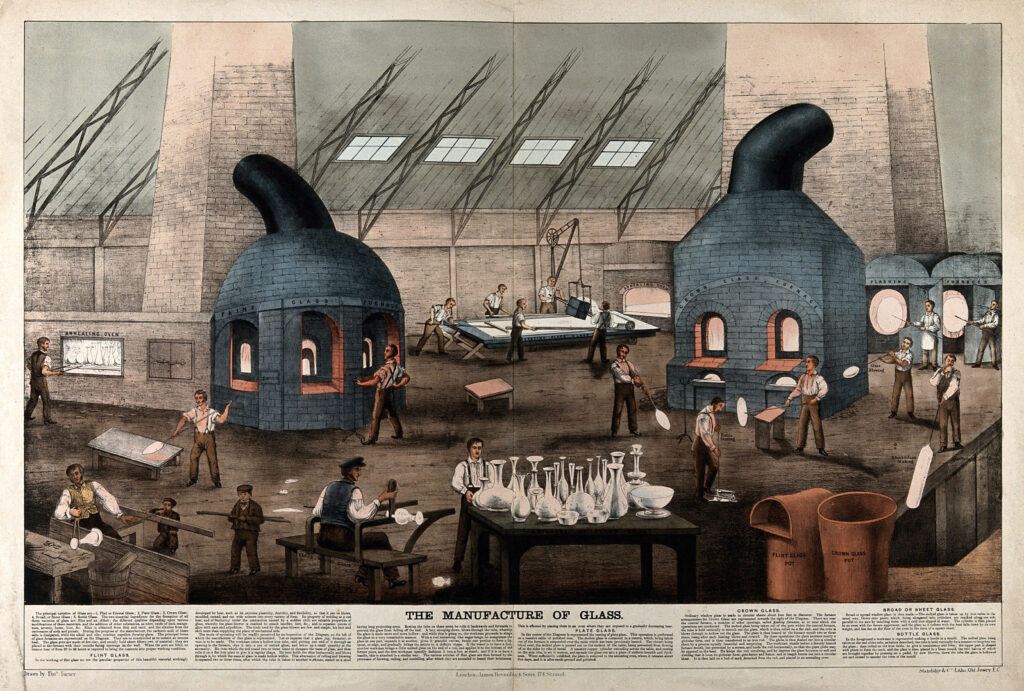

The Glassblowing Factories of Lancashire

Glassblowing has always been regarded as an art, but in the 19th century, it was also a deadly occupation. Lancashire, once a major center of the glass industry, produced everything from windowpanes to delicate goblets. However, working near furnaces burning at over 1,000 degrees Celsius posed extreme risks. Inhaling glass dust and enduring constant exposure to intense heat led to severe respiratory diseases and chronic burns. Many glassworkers did not live past the age of 40 due to hazardous conditions and the lack of safety measures.

In 1899, around 1,800 glassworkers in Lancashire protested against worsening working conditions following the passage of the 1895 law, which prohibited 13-year-old boys from working night shifts. This change resulted in a labor shortage, increasing the burden on remaining workers and exacerbating already dire conditions.

Mines and Metallurgical Plants

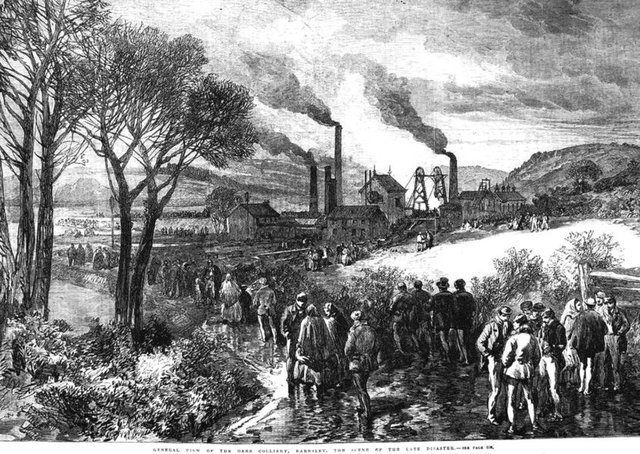

Mining and metallurgy were the backbone of Britain’s Industrial Revolution, but progress came at a staggering human cost. In major cities such as Manchester, Birmingham, and Sheffield, coal extraction and iron production claimed countless lives. Men, women, and children toiled for 12 to 16 hours a day, facing the constant dangers of cave-ins, explosions, and gas poisoning.

One of the most devastating events of the time was the Oaks Colliery disaster in Yorkshire. On December 12, 1866, a series of methane explosions tore through the mine, killing 361 miners and rescuers. It remains the deadliest mining disaster in England’s history. The explosion was so powerful that it was heard three miles away, and plumes of smoke and dust rose from the mine, covering the surrounding area in soot.

Conditions were no better in Sheffield’s steel mills, renowned for their foundries. Workplace accidents — such as falling into vats of molten metal or being injured by moving machinery — were tragically common.

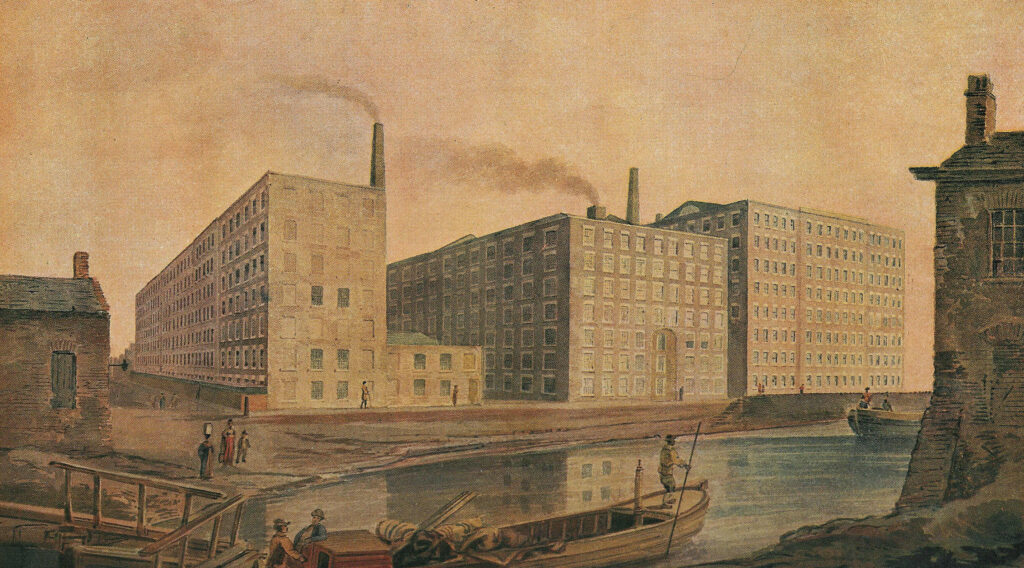

Manchester’s Infernal Kitchens

In the factories of Manchester, dubbed the “Cotton City,” workers endured 14 to 16-hour shifts. However, even harsher conditions existed in bone-rendering and tallow-processing plants. Workers toiled amid rotting animal remains, sweating profusely in sweltering heat while inhaling foul fumes, just inches away from deadly industrial machines.

Victorian Manchester was notorious for its slums and unsanitary conditions. Workers lived in overcrowded, poorly ventilated homes with no sewage systems, which fueled the spread of disease and high mortality rates. In 1837, the Manchester Statistical Society reported that the average life expectancy of the city’s working-class population was just 17 years.

A Grim Legacy

In the end, these tragedies and the gruelling labor conditions of the past became the catalyst for reforms in industrial safety, housing, and workers’ rights. Should we romanticise the industrial era? Perhaps, but it is crucial to remember its dark side. Those who built Britain’s wealth often lived in poverty and suffering. Their stories serve as a stark reminder of the human cost of progress.