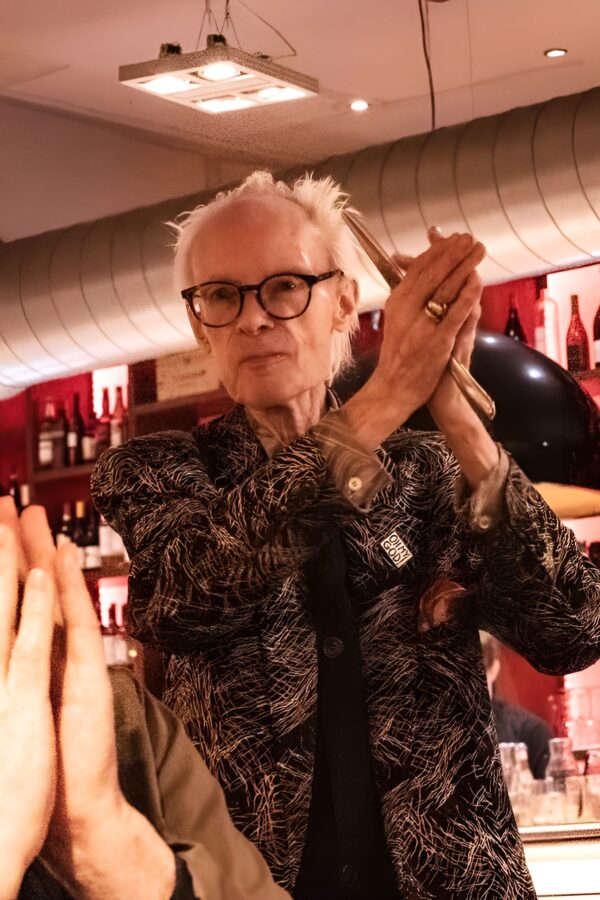

Memoir at Midnight. Alexander James meets ANTHONY FAWCETT, the Night Owl of Chelsea

In the heart of the counterculture era, ANTHONY FAWCETT was a youthful curatorial assistant to John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Today, a renowned art critic and socialite, he remains a mysterious figure—one of the few holdovers from the old guard of the art world. A long form interview with the night owl of Chelsea.

It’s nearly midnight in Chelsea. I arrive at Anthony Fawcett’s flat in Cremorne Estate, just off the King’s Road, where I’m greeted at the door by a departing Louis Schrey, a Berlin-based multidisciplinary artist, who’s just shown Anthony some video works for an upcoming exhibition that Anthony is curating, From Hollywood to Whetstone.

At 77, he’s more active than most 17-year-olds and a complete night owl. Still in the thick of it. A glance at his Instagram reveals late-night parties with Boy George, Tracey Emin, pre-views, launches and more. I’ve heard the rumour that he doesn’t get out of bed before 5 p.m – we were originally scheduled to meet at 9pm, but he pushed it back. And back.

His quirky ground-floor flat is a living arts archive of the past fifty years. Arts magazines stack on stained paperbacks and all crowd the bedsit floor. Damien Hirst designed Beck’s beer bottles sit on windowsills, Dali prints and a ‘Peace’ print signed by Yoko Ono hang on the walls, alongside East African masks — art in a complete medley. Everything has a story, and I know I’m not there long enough to hear them all – it’s one of those rooms.

I wonder what’s going to come up first from this man who has moved between eras and across social groups on both sides of the Atlantic for decades. An Abingdon educated upper class boy in the midst of the avant-garde.

As Anthony pours two reds into a couple of already-stained glasses, Mr Maurice, his half-Bengal cat, begins to hump my backpack. I tell Mr Maurice his masters room could do with some curating. We sit in the only two wicker chairs while he talks me through the artefacts, creativity, and chaos splayed across the room.

“Chet Baker or Miles Davis?” he asks, in a cut-glass English accent, pulling a tape from the shelf.

It’s no mistake that within the first five minutes, he mentions Malcolm McLaren. His new King’s Road flat, just off the Moravian Church, is directly opposite Vivienne Westwood’s and Malcolm McLaren’s World’s End Sex boutique. There’s something about Fawcett that epitomises that King’s Road glamour and punk of the 70s and 80s.

Anthony Fawcett’s raconteur style belies the fact that he has had an industrial arts career. If he wants to sit and tell the old tales (and they are good ones), then I’ll let him.Although you burst onto the art world scene in the 60s there is also a disconnect in the way your arts life has come about.

I’m a great follower (like Malcolm McLaren was) of the situationist movement in Paris. The Situationists say you never go from A to B – on your way from A to B, you take many detours, and it’s the things that happen on that detour that change your life.

If I look back on my life, I was very lucky. Like Lennon and Yoko.

That’s some luck. You seem always to have been in the right place at the right time, spinning on the zeitgeist of every art fad decade there is. One of the stories that floats around online – you brought Man Ray to london?

Meeting Man Ray, yeah.

It was 1966?

1967… I’ve always worked by myself. There was this job for a crazy American publisher Ed Newman who wanted someone who could introduce them to artists like Henry Moore and Francis Bacon. So, I went to the interview because I knew all these artists.

How old were you?

Yeah, I was about 20, not a year out of the Ruskin School of Art…

Which you had dropped out of?

Yeah, I left after a year when Mario Amayer asked me to be the art critic at Art and Artists, quite an edgy magazine. Not long after I was writing for Vogue magazine – I also got invited to be art critic of a very influential art magazine in Paris called Opus International. So I was reviewing all the London exhibitions.

I got the job right away. I was working in the Apple Saville Row offices, right across the road from John and Yoko’s with Bag Productions. One day, Ed Newman asked me if I knew Man Ray and if I could go and see him — “we need a lithograph”.

So we went to Paris.

Just like that…

He didn’t know that I didn’t know Man Ray, right? So we get to Paris, we’re in the airport, and I’m not sure how I was going to handle it, while we were waiting for the bags. And in the waiting hall, there was a telephone, right? So, I went to the telephone. There was a telephone directory, you know, for Paris. And I just thought, well, I’ll look up Man Ray in the book. I called him right there.

And then Ed was waiting for our bags.

Hilarious.

“So, er, hallo Mr Man Ray, it’s Mr. Fawcett, art critic from London, we wondered if you might be interested..” And he said, “Oh, come around for tea at four o’clock.” Oh, thanks. Thanks, man. So without missing a beat. I went back and then Ed was getting the bags. We’re going for tea with Man Ray, right? Four o’clock. I mean, in my life things have somehow worked out.

Serendipitous, like a novel or an episode of White Lotus.

Serendipity, exactly. So we went to tea with Man Ray, it was fantastic. There was his wife, Juliet Man Ray, in his famous studio in Montparnasse, sitting behind the screen designed by Marcel Duchamp. He lived in Paris for half his life, but he had an American twang from Philadelphia. He’s absolutely charming. Must have been quite old, in his 70s, and, you know, he agreed right away. He loved to do the lithographs for Ed, which he did do. And we stayed the night.

And the next day, he took me to lunch. So he lived just down from Saint Sulpice, where actress Catherine Deneurve lived in the opposite corner, we went to his favourite restaurant, Au du Canet. And I made a mistake of ordering what Man Ray ordered. I thought it was a steak, because I love steak when it is absolutely raw steak tartare with a raw egg. And I never in my life, and that night, you can imagine, in the middle of night in my hotel, I was sick as a dog, all night.

Oh yeah..

Steak tartare…small price to pay, yeah

Good story. Bon appetit…

Yeah! So within a month or two, we proof the lithograph. It was a lovely painting of Man Ray’s The Rope Dancer’s. We did a small edition. I can’t remember two, 300 and invited Man Ray to come to London to sign them, and I got an interview.

And hence, Man Ray comes to London. He hadn’t been before? This is one of the myths (or the legends) that hang around you…

He probably hadn’t. I mean, famously, Salvador Dalí came to the first series, List One, because they were all friends of Roland Penrose, right? And if you remember the history, Salvador Dalí dressed up in a diving suit at the opening of the Bozar Gallery, and he was quite scared because he couldn’t get the helmet off — he nearly suffocated, actually.

There’s the famous photograph of him…

I don’t know if Man Ray came or if he came before, but anyway, he did come. We paid him to come. We put him up at Brown’s Hotel.

I can’t imagine that being possible today – it would take a lot of gaul anyway. So, you were immersed in the art scene – how familiar were you with the Beatles at this point?

Oh, okay, my father worked at the EMI factory, yeah, which, of course, EMI is famous for the dog on the logo, ‘His Master’s Voice’, pressed records.

Because he was from the EMI club he would get them for free, you know? So every single Beatles record, the first one I got was from my dad. So I was very close to the Beatles from the very first album, never imagining that, literally, four or five years later, I’d be one of the closest people in the world to John Lennon.

So how did you get to meet them?

It was 1968. It was another one in a million chance. I was at the opening in the Arts Laboratory in Covent Garden, Yoko was there, and I had already met her.

As the art critic of ISIS (The Oxford University arts magazine), I came up to London to interview her, and I went to her flat in Regents Park where she lived with her husband Tony Cox and we got on like a house on fire. I was writing about her a lot and I understood her art extremely well.

So you knew her before most in the UK did?

She was really very well known in New York before Lennon. She was part of Fluxus. (An experimental art movement of the 1960s that blended art with everyday life). When she came to London, nobody heard of her except people like me.

She had heard I was on the organising committee of a big exhibition up in Coventry called the National Sculpture Exhibition. Fabio Baracla, who was the chairman, had appointed me because I’d written for his magazine, Sculpture International.

She said, ‘Anthony, I’ve heard you’re working on this exhibition. Do you think you could, you know, get some of mine and John’s work into it?’ I said, ‘Well, I don’t know, I’ve never met John.’ She replied, “Well, you’d better come over and meet him.”

So your paths crossed again… and then?

So I come over, and John’s sitting on the stairs. He’s got a cap on. He’s got a beard. ‘How are you?’ he says, and within five minutes, he says, “Let’s go to dinner.”

So we go outside, and there’s this big white Rolls Royce. You’d think we were going to some well-known, fashionable restaurant, but no – we literally go around the corner for five minutes and end up at a small Indian restaurant. It wasn’t what you’d expect, but we sat in the back, and John didn’t even order Indian food – just fish and chips. We talked about the exhibition, and I told him I needed to understand the scope of the work. He agreed and then asked where I lived. I said, ‘Parsons Green,’ and he offered to give me a lift.

When we got to my house, John was amazed by the paintings on the walls. They were by his old art school friend, the painter Jonathan Hague.

Another amazing coincidence.

Absolutely. John had recently become close with Hague, and when Hague needed a place to store some of his paintings, I offered to keep a few at my place. When John saw them, he was surprised to see his old friend’s work there.

And that somehow sealed your destiny with John Lennon, at least it has a ring of destiny around it.

Something going on, yeah… A few weeks later, I was invited to the Beatles’ office, which wasn’t yet the Apple building. I met John, Yoko, and the others at Abbey Road while they were working on what would become The White Album.

How old are you here?

I was 21. It was my first time at Abbey Road, this huge building with grey corridors, and we walked up to a big door. They opened it, and suddenly I was in this huge studio. I’m in the room with the Beatles. Ringo’s behind the drums, Paul’s sitting there, George is there, and John and Yoko are sitting on the floor in the corner, all in white. The music is blaring loud. I’m just sitting there thinking, “Wow.” After a while, we went back up to George Martin’s tiny room with the control console. It was overwhelming, being in the room with the Beatles. It was surreal.

I mean, they are superstars of the counterculture era – I’m not surprised.

At Abbey Road, we discussed the exhibition. John and Yoko had this idea for a conceptual sculpture involving two acorns planted east to west, symbolising their love and the connection between east and west. Fabio, the curator, was skeptical but agreed to include it. The acorns were meant to grow into trees, and they eventually did.

We sat there, and I told them, “Okay, I need to know what your sculpture is going to be. Fabio’s asking about the scope.” John and Yoko were giggling and whispering to each other. Then John said, “It’s going to be two acorns planted east to west. They’ll symbolise our love and the connection between east and west, and they’re going to grow into trees.”

Hard to take something so… unconventional seriously, at first…

But at that point, imagine me going back to Fabio — serious curator of Sculpture International, working on an exhibition with Henry Moore and all these grand sculptures — and telling him, “Well, John and Yoko’s sculpture is two acorns.” And amazingly, Fabio went along with it. Conceptual art, after all.

It’s funny that the symbols for protest today are people like Bono and Bruce Springsteen – friendly with the liberal establishment – it’s not a comparable time – popular musicians exactly reflect real political protest.

John and Yoko also wanted to do a catalogue for the exhibition. I was tasked with organising it, but it was too late to get an official catalogue. John said, ‘Come into our office tomorrow—we’re doing the catalogue.’ So, I went into the Beatles’ office off Wigmore Street, and there were people everywhere. I went into the back room with John, and Yoko said, ‘Look, here’s a desk. Let’s do our own catalogue.’ We made a very conceptual one—just tracing paper, a title on the outside, and inside, I wrote a small paragraph. It’s still around, though I don’t have a copy.

Within a few meetings, you were organising this?

Within those first three meetings, I was organising the exhibition and the catalogue.

When it actually happened up in Coventry, we got all the photos, including one with the argument with the Canon of Coventry Cathedral. In that photo, you can see John and Yoko, and there’s a row going on between the Canon and them.

The big problem was that John and Yoko weren’t married, and that was a huge issue for the cathedral. They said, ‘Because you’re not married, we can’t display your work with all the other sculptors.’

That’s a historic argument. If that happened today, no one would bat an eye.

Sure but Yoko got absolutely furious and told me, ‘Anthony, will you please get Henry Moore on the phone? Tell him to speak to the Canon and sort this out.’

Luckily, Henry Moore didn’t pick up. I knew him quite well—he was always very nice to me, and I’d visit him in his garden. I still see his daughter, Mary Moore, quite a lot.

I wonder what Moore would have said…

We had to compromise. I found a space just outside the cathedral, where we planted the acorns. John and Yoko decided we’d have something around the acorns, so they had a circular seat built around them. The idea was that the acorns would be in the middle of this peaceful space.

“Guess what happened? The local newspapers reported that, two days later, someone came and dug up the acorns overnight!”

Funny enough, those original acorns that were stolen were recovered this year—returned by a police officer—and are now on display in the Beatles Museum in Liverpool. Acorns stolen, then found decades later. They’ve come full circle.

Isn’t that amazing? A couple of weeks later, we had to go back and replant them. This time, they stayed in place. And years later, they grew into trees. Yoko was invited to see the trees in a special ceremony, and I was invited, too. It was amazing to see how they really did become trees.

Because that almost wasn’t the point? It was conceptual, part of a performance, they got stolen….

The acorns were part of their peace campaign. They even sent them out to world leaders at the time, as a message of peace.

What other curatorial work did you do with Lennon and Yoko?

Yes, later, we worked on John’s lithographs with Ed Newman. We sent John litho paper, and he could draw on it, then bring it back to be printed and after a few weeks, I got a call from him. He said, ‘Anthony, I’ve got hundreds of drawings, come and see them!’ So, I went over, and there were all these beautiful drawings—some were of Yoko, naked, and really stunning, others were more abstract. We selected about 18 or 20, and they were all gorgeous. The lithographs were done in a beautiful white leather case designed by one of the top designers of the time. The first piece in the collection was a poem, from A to Z, which John had actually written for Apple.

John did come into the studio at one point and worked on the frontispiece of the poem himself. He etched it onto a zinc plate in the studio.

The exhibition, which opened at the London Arts Gallery on New Bond Street, was a big success. But on the second or third day, the police raided it, took the artwork down, and it went to court. The lawyer presented examples of Picasso’s works to the judge, and the case was dismissed. The exhibition continued without issue after that.

When was the last time an artist got raided by the police over plagiarism concerns!

A month or two later, John was invited to show his works in New York, but due to his legal issues, he couldn’t get into the US—something to do with a previous drug bust, which we suspect might have been planted by the police. So, I ended up going to New York instead.

Actually, I didn’t tell you. After I started working with them, almost every month, I had to fly to New York to represent John at the business meetings. Alan Klein, yeah.

So this was 69?

Yeah, I remember 1969 very well.

They say if you remember the 69 you weren’t really there! So you must have been there for the Beatles split?

So, the Beatles essentially ended in April 1970. John had actually tried to break them up earlier, in September of the previous year. He wanted out, but Paul wouldn’t have it. Paul didn’t announce his departure until April, which made John furious. He felt like Paul was taking credit for breaking up the band, even though John had been the one to suggest it first.

I’ve got the tape of that conversation somewhere. One day, I’ll play it. It’s the time when the Beatles were breaking up…

A lot of people would like to hear that..

Yeah… At this point, John and Yoko were already thinking of moving to LA and closing down the office. They invited me to come with them for ‘primal therapy,’ but I told John I was going to take some time off, write my books on art and sculpture, and visit Spain. I said thanks, but no thanks, and we kept in touch.

Now, John didn’t go to the Toronto Rock Festival, even though he and Yoko had planned to attend. It was a big event, with all the top rock musicians in America, and they’d invited the Beatles to be part of it. But on the day of the event, John and Yoko didn’t feel well, so they decided not to go. They asked me to cancel, but I didn’t. An hour later, I found out Eric Clapton was at the airport, waiting with all the other musicians. I told John, and he suddenly perked up, realising they hadn’t actually cancelled. So, we rushed to the airport, and off we went.

Sounds like a strange position, almost a mediator between John and Yoko, as well as between the other Beatles.

Yeah. That was the first time John played with a band that wasn’t The Beatles. Eric Clapton, Alan White, and others were part of the ‘Plastic Ono Band,’ and it was fantastic. On the plane, they didn’t know what they were going to play, so they were just practising old rock and roll songs. It was an exciting time, but what I remember most is how I was kind of the bridge between John and Yoko. I was always in the middle, looking after both of them.

In the car, John would ask, ‘So, Andy, did you speak to George? Where’s Paul?’ Yoko would ask if I got through to someone else. It was my job to handle their lives. I was sort of the go-between for both of them, helping with the practical side of things.

Looking back, I never realised how significant all of that was going to be. At the time, I was already well known in the art world, and I was just part of the scene—helping them, going to art openings. It just felt like an extension of my life, nothing more.

A slight sad and sensitive edge had entered your role, I guess. A lot of hurt there, given the complexities at play, the unravelling. Break ups are sad – were you around for Yoko and John’s split?

Well in the early 70’s, I knew May Pang quite well. In fact, I almost went out with her—she was quite attractive—but in the end, I went out with Esther, the Jewish girl from Alan’s Klein’s (the Beatles US manager) office.

Of course, later on, you must know the story. Yoko kicked John out, and as part of it – she actually instructed May Pang to have an affair with him while he was in LA. It was all part of the strange circumstances surrounding their separation.

That’s what they call The Lost Weekend..

The lost weekend, yes.

And that affair became the inspiration for John’s album Walls and Bridges. It’s a fantastic record, produced by Phil Spector. Most of the songs are about John’s affair with May, his great passion at the time. If you haven’t listened to it, I highly recommend it.

The album covers are full of John’s drawings from when he was about 10 years old—really funny photos too. It’s a special piece of work.

Lennon is now viewed as an icon for peace. Do you think this is an oversimplification? Weren’t these times more complicated? In many ways, he was an agitator (for the counterculture) rather than just a pop icon or peace symbol, particularly with some of his later work – although not a lot of people understand that.

John and Yoko were absolutely committed night and day to working for peace in the world. I mean, seriously, seriously. I mean, can you imagine a typical afternoon we’d get in the office around two o’clock, and I’d have the list of the interviews between two o’clock and six o’clock. It’d be quite normal to do 10, 20, 30 media interviews every afternoon, everyone perhaps an hour. I mean, they gave their time, unstintingly, to talk about peace and what the world should do. Really, really seriously.

In retrospect, would you say you helped define their image as, or at least John’s image as, you know, a peace symbol.

I would say they were so strong, especially John – of the whole peace campaign. But what we could say was I was the one that had to make it happen. So for instance, when they made these posters called War Is Over, which is great, they wanted them to be on billboards, not only in London and Europe, but all over the world. So who’s going to get on the phone and organise how to get these billboards up all over the world, even on the border of Hong Kong? Me, in Paris, yeah. So it’s pretty amazing, but I didn’t really think of it as a complicated job. It was just what we all did. It was like a family, entirely natural.

But some considered Lennon an agitator – for revolution?

You know, it was absolutely true that Nixon and J Edgar Hoover tried to get him out of the country. Yes, and there is still, there’s still a conspiracy theory about Mark Chapman shooting John Lennon.

People say you were John’s assistant. It doesn’t sound like it…

People would say, ‘Oh, it’s Anthony, he used to be John Lennon’s assistant.’ I’d correct them, saying, ‘Excuse me, I wasn’t John Lennon’s assistant. I was John’s curator. I had assistants.’

Is the tape you mentioned, of the breakup, in the archive? Many of your interviews, recorded or in print, are stored, not released to the public. They would be of interest to many people – what are your plans?

Big plans. I’m working with Adrian Glew from the Tate to move them into the Tate archives. It’s going to be the “Anthony Fawcett Archive.” Just a few weeks ago, if you came here, you would have found boxes piled up to the ceiling, just here – Guinsun Jang, my artist friend, based in Berlin and Korea, but she was in London – she’s very kind, she helped me move them.

Let’s fast forward. After living in California for a decade, you return to London during a time of real upheaval under Thatcher’s government and Reagan’s Britain. There was a huge burst of creative energy in both cities — the London club scene, a fusion of fashion, art, and music, Soho, and the East Village. You were a staff writer at The Face magazine, a trail-blazing youth culture and style magazine that has shaped the creative and cultural landscape in Britain – it’s fair to say you interviewed almost everyone: current musicians, major artists, filmmakers, and architects.

Well I was part of a small team at The Face for eight or nine years in the early days. Every month, we published huge articles on photography, art, architecture — big things, small things. We covered icons like Francis Bacon, Andy Warhol, David Hockney, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Cindy Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe, Julian Schnabel, Gilbert & George, Vivienne Westwood, Keith Haring, Brian Eno, Tracey Emin.

And where does your art sponsorship work come into this? In the 1980s and 1990s, sponsorships became more strategic as companies recognised the power of aligning with culture and high-profile artists for their branding – you had a few big names – Montblanc, Haagen-Dazs, Texaco, B.P., Hugo Boss… It’s a big part of your career, connecting these worlds.

The Face was my entry into the advertising world. That’s how I started Anthony Fawcett Associates. At that time, The Face opened doors to almost anything. Advertising agencies wanted to tap into my network and insights, so that’s how I got my first client, Beck’s beer. My first budget was £7-8000, but there was a big exhibition at the Royal Academy on German 20th-century art. At the opening, the CEO, Alison, came down, and I briefed him at the pub. He ended up meeting Margaret Thatcher, and he jokingly said, “We’re not paying him very much, are we?”

Within three years, my budget grew to £400,000 annually, and the Beck’s Arts Programme became a massive success. Over the years, Beck’s put in £15 million.

Then, Beck’s asked me, “Could you do in America what you do here? We don’t have much money, but we can give you a million dollars. Could you do something with that in a couple of months?” Well, of course, I said yes!

As you would…

The first thing I did was the Whitney Biennial, which was a big deal in the American art world. I knew the director, David Ross, and we worked out a deal for Beck’s to be the sole sponsor. We partnered with David Hammons, a well-known African-American artist, to create a limited-edition Beck’s bottle. He wanted to work on the black Beck’s bottle, and the result was fantastic. It was a huge success, getting tons of press and publicity.

We had enough money to fund another big event in America. So, there was this very well-known art museum in the middle of America, in Baltimore. I met the director in London through some events, and he was the first museum director to put on a massive show. It featured what we now know as YBAs (Young British Artists)—Damien Hirst, Rachel Whiteread, the Chapman Brothers, and everyone. He asked if we could put some money into it to help, and I thought, ‘Yeah, why not?’ So, Beck’s became the sponsor for that big exhibition. I suggested, ‘Why don’t we do an artist’s bottle as well, for the Americans?’ So we did the Damien Hirst bottle with the spots and Rachel Whiteread’s bottle with the house on it. All the artists turned up, except for him, and it was a huge success.

And the 90s? Did you have any involvement with the Young British Artists (YBAs)? It’s an understatement that they played a big role in transforming modern British art. I know you worked with Charles Saatchi, an early and major supporter of the Goldsmiths troupe.

I started helping Charles in 1987 Well, the second show ever at the Saatchi Gallery, I got the call from Charles, as He’d seen all the huge amount of present TV I got for the Andy Warhol Foundation retrospective..

So I was quite surprised to get a call from Charles Saatchi. He was very private. He wouldn’t give any interviews to anybody. He said, “Could you come tomorrow, 10:00 AM or 12:00 PM? No outsiders involved.”

He told me, “I saw what you did for the Warhol Foundation Event. I was really impressed by the press you got for it.” Then he explained, “I’ve got a problem. Not enough people know where the gallery is, and not enough people are coming. Would you consider consulting for three months? I’ll give you a fee, and maybe you could help get the word out?”

Of course, I said yes. I had three months to work on it, and the fee was reasonable—can’t remember exactly, but it was around £100 a month. It wasn’t much, but it was a start.

And so I had three months to do it, you know, a three month contract. The exhibition coming up the next month was amazing. It was his second show, with huge paintings by Kiefer around the walls and massive Richard Serra sculptures in the middle of the gallery. They had to crane the sculptures in through the roof—it was incredible. Lady Gagosian did the same thing in the Gagosian gallery in King’s Cross.

The one after, it was the first-ever Neo Geo show, a series of exhibitions Charles did with American artists like Jeff Koons, Ashley Picket, and others. It was the first time Jeff Koons was showing in London, and he brought his “gym” sculptures, the amazing sculptures of baseball bats. It was the best of Koons’ work.

I went to all my editors and friends in TV and magazines, and they loved it. I got massive coverage—12 pages in the Sunday Times color section and TV news coverage. I even kept a copy of all the press I secured—every newspaper, every magazine. I have it all in my flat.

Charles was really happy with what I did. So, yeah, I did my job. I still have the best little black book in London, though I don’t use it much anymore.What’s the time, do you want to have a break?

Yeah Anthony, that would be good, wouldn’t mind a break. It’s 1:30 AM on a Wednesday, I’ve had my fair share of dates, memories of bygone decades. Surely even night owls need to sleep.

Anthony Fawcett is author of:

John Lennon: One Day at a Time, 1976

California Rock, California Sound: The Music of Los Angeles and Southern California, 1978

New British Interiors (Zaha Hadid, Nigel Coates, Anthony Fawcett), 1991

The exhibition Anthony Fawcett is curating, From Hollwood to Whetsone: Crossing Continents will be on display at the x restaurant and garden, 10th April to x April

Comments are closed.

1 Comment.

What an amazing character!