Golden Cloaks, Stone Drums and Wooden Figurines: Britain’s Strangest Artefacts

Archaeology is a science of the past — but some parts of the past refuse to reveal themselves easily. Britain is home to many strange and baffling objects that have defied classification for decades, even centuries. They don’t fit neatly into any known category: not quite weapons, not exactly tools or ornaments — or sometimes all at once. Dug up from graves, bogs and fields, each one raises more questions than answers. What is it? Why so complicated? Why does it even exist? No one really knows. And that’s part of the fascination. Here are some of the most intriguing examples.

Carved Stone Balls from Scotland

At first glance, they look like ordinary stones. But don’t be fooled. These Carved Stone Balls are mostly found in northeast Scotland, though a few have surfaced in England and even Ireland. About 7 cm in diameter, they date back to around 3000 BCE. Some are adorned with intricate geometric patterns; others are studded with protrusions or knobs — often six of them.

Were they tools? Symbols of power? Something else entirely? Some researchers believe they were used in divination; others suggest they were sling projectiles. One theory holds they were weights for ancient scales. But none of these ideas has ever been proven. What’s especially mysterious is the extraordinary precision: most of the balls are perfectly balanced and exquisitely crafted. Who made them, and how? No one knows.

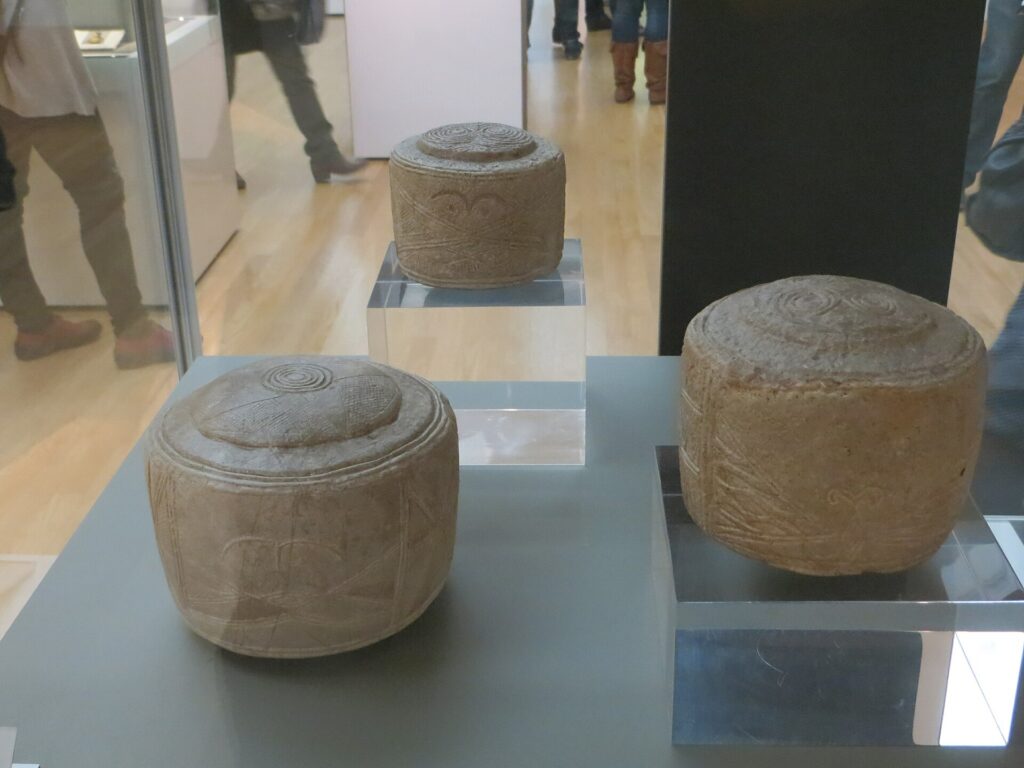

The Folkton Drums

They look like toys — small chalk cylinders decorated with carved patterns, more than 4,000 years old. In 1889, English clergyman and amateur archaeologist William Greenwell excavated a burial mound in North Yorkshire and found a group grave dating to the time of Stonehenge. Among the dead was a child, buried with three chalk “drums”. Why call them drums? Simply because they resemble them — and not much else.

For a long time, their purpose was unknown. But in 2018, researchers discovered that the circumferences of the drums correspond exactly to measurements of 8, 9 and 10 feet. This suggests they may have been measuring tools — ancient equivalents of tape measures — possibly used during construction. If true, it’s a sign of remarkable technical knowledge among Neolithic Britons. Then again, it’s still just a theory.

The Mold Gold Cape

In 1833, workers in Wales stumbled across an astonishing find: a stone burial chamber containing a skeleton draped in a delicate golden cloak. The sheet of gold, elaborately embossed, was once studded with nearly 300 amber beads — most of which have since disappeared. The artefact weighs nearly two kilograms and dates to around 1900 BCE.

The problem? You couldn’t wear it in any practical sense. It doesn’t bend, covers only the shoulders and chest, and restricts arm movement. It’s not armour, and it’s not clothing. Most likely, it was ceremonial — a priest’s garment, or the regalia of a ruler who claimed semi-divine status. Based on the other objects in the grave and the size of the cape, it may have belonged to a woman. Or perhaps it was never worn in life at all — a burial costume made for the afterlife alone. A riddle with a touch of surrealism.

The Roos Carr Figures

In 1836, near the village of Roos Carr in East Yorkshire, workers digging a canal (not the same ones from three years prior) discovered a box of wooden figurines. These were humanoid statuettes with exaggerated features and eyes made of quartz. Some had detachable genitals. They came with miniature shields and weapons, and the whole crew was arranged in a boat with a snake’s head at the prow. In short: complete madness. They date to around 600 BCE — the Iron Age.

Were they idols, toys, ritual dolls? Some researchers think they were offerings to fertility gods; others suggest they represented ancestors. But perhaps the most extraordinary thing about them is their state of preservation. The wood lay buried in the earth for two and a half millennia, and thanks to two metres of dense peat, it remained almost entirely intact.

The Roman Dodecahedra

Small, hollow, twelve-sided bronze objects with round holes of varying size and odd little knobs — these are the strange creations of Roman metalworkers in the 3rd century CE. The first was found in 1739 north of London, and now over a hundred have been discovered — in Germany, Austria, France, Belgium, Hungary, the Netherlands, Switzerland… just about everywhere in Roman Europe except, ironically, Italy. Britain has yielded a particularly high number, with the most recent unearthed less than a year ago — from burial sites, coin hoards, rivers and bogs.

What were they? Measuring tools? Ritual items? Craftsmanship tests for apprentice metalworkers? More than fifty hypotheses have been proposed, but none confirmed. What makes the mystery even trickier is this: despite their widespread presence, Roman dodecahedra are never mentioned in any known written source. As they say — a true enigma.

***

Each of these artefacts is like a torn-out page from a book written in a language we’ve almost completely forgotten. We can guess, compare, speculate. But the real story slips away — they remain silent witnesses of another world, one in which people believed in things we can scarcely imagine. History still has plenty of blank spaces. And perhaps that’s what keeps it alive.