The Night’s Cipher

Disclaimer: This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

The novel might include references to real historical figures and events; however, these references are fictionalised and not intended to accurately portray historical facts. The author has taken creative liberties in the depiction of certain individuals and organisations. The characters, organisations, and events portrayed are not intended to reflect any real-life persons, organisations, or beliefs.

Certain themes in this book might be sensitive to some readers. The author has endeavoured to handle all subject matter with respect and care. Readers are encouraged to approach the material with an understanding of its fictional nature.

The views and opinions expressed in this novel are purely those of the characters as created by the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of any real persons (including the author), organisations, or groups.

About the Author

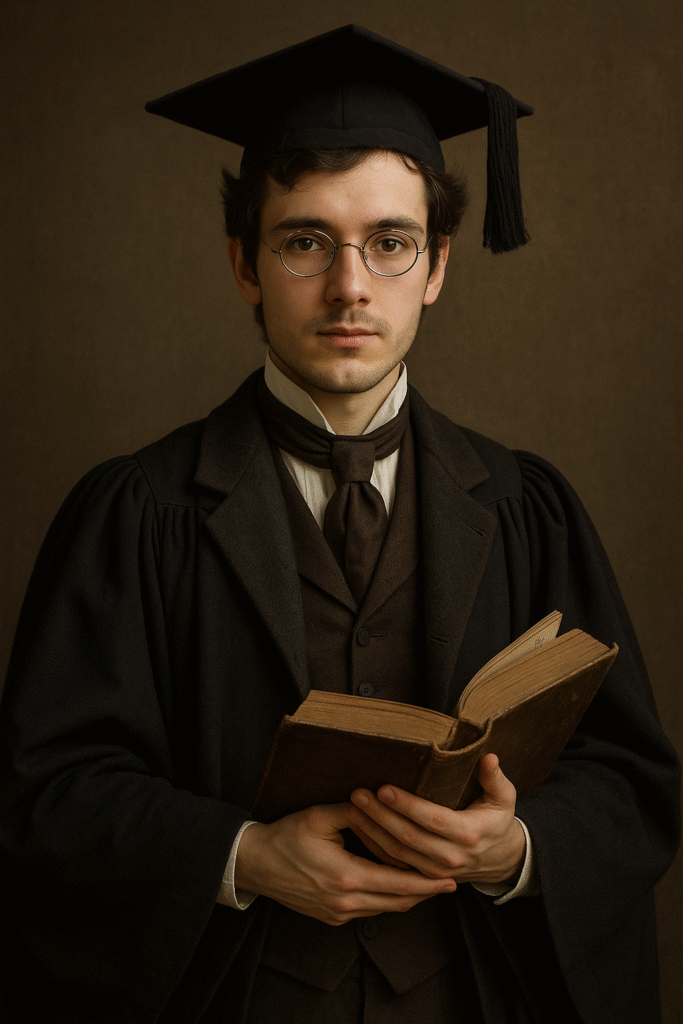

The archive of Professor Paul Gordon James—long thought lost—has now been unearthed and made available for the first time. Born in Bath, Somerset, on July 4, 1870, Prof. James pursued his education at Christ Church, Oxford, before continuing his postgraduate studies at the Royal College of Science in London under the guidance of Prof. Reginald Dixon.

The collection of his papers, chronicled in ‘The Night’s Cipher’, provides remarkable insights into 19th-century history, the nature of consciousness, and artificial intelligence—along with shocking revelations that may finally expose the true identity of Jack the Ripper. Equally controversial are the records concerning Prof. Dixon, a man whose actions remain the subject of fierce debate.

A collective of scholars, recognizing the profound historical and philosophical implications of these writings, has taken it upon themselves to preserve and publish them. With the support of Atmosphere Press, Prof. James’s long-hidden work is now available to the public, allowing readers to explore the mysteries he left behind and determine the truth for themselves.

Chapter 1: The Tragedy and the Savant

Back in the year of our Lord 1888, while still a boy at St. Peter’s School, I experienced the first true tragedy of my young life. Edward Hastings, my closest friend and confidant, vanished from this world under circumstances that defied understanding. We were inseparable, Edward and I, spending countless hours lost in the pages of Principia Mathematica, unravelling the elegant complexities of gravity, of motion, of the very fabric of the universe.

Edward’s body was found by one of the groundkeepers beneath the ancient oaks that bordered the school grounds. The authorities, quick to dismiss the matter, ruled it a tragic accident – a simple fall, they said. Soon rumours began to reach me; disturbing, pervasive rumours which suggested that Edward’s body was found heavily mutilated, his skull crushed, his face disfigured beyond recognition. I could neither confirm nor deny these rumours, for all that I was allowed to witness was a closed coffin.

The last time I conversed with Edward, we took our customary place beneath the ancient oaks – those silent sentinels of our boyhood – unaware that they would so soon bear witness to his untimely demise. The waning light of evening stretched spectral fingers across the dampened earth, as though nature itself sought to inscribe a warning we had not the wisdom to heed. He was uncharacteristically quiet at first, tracing invisible equations onto his sleeve as if struggling to find the right words. Then, in a hushed, almost reverent tone, he said, “Paul, have you ever considered that we might be looking at science the wrong way? That there are…forces, principles beyond what Newton or Leibniz ever imagined?” I gave a derisive laugh, prepared for yet another of his customary philosophical musings; yet there was a singular, almost frantic, light in his eyes that unsettled me in a manner I could not at once define. “I met someone,” he continued, lowering his voice. “Someone who has shown me things – things that make our mathematics seem like mere children’s puzzles. I don’t know whether to be terrified or elated, but I swear to you, Paul, nothing is as we thought it was.” He hesitated then, as if debating whether to say more, but instead he simply clasped my wrist and whispered, “If something happens to me, promise you’ll try to understand.” And then, just like that, he was gone – walking away into the descending dark, leaving me with nothing but questions I would never get to ask.

I knew in my heart it was something more, something darker, that had taken Edward. The oak’s roots at the place of Edward’s alleged fall were oddly disturbed, as if there were a struggle. As soon as the opportunity presented itself, I conducted my own search at that accursed place. I started digging at the base of the old oak until I saw a shiny object that looked like a medical implement, a curiously shaped scalpel.

I put the object in my pocket as soon as I heard the approaching steps. Mr. Sutcliffe, our physics teacher, was walking towards me, his face stern with disapproval and suspicion. He was accompanied by another figure, clad in formal black, who looked more like a government official than a school teacher. The pair emerged from behind the oaks like a sudden, unstoppable menace.

The rebuke of Mr. Sutcliffe, cold as the grave and twice as pitiless, carried within it the weight of both mockery and censure. “White, if you were expecting to see here the word RACHE written in blood, I’m sorry to disappoint you. Right here, right now, you are committing sacrilege by desecrating the memory of your alleged friend, who died in a tragic accident. And tragic does not by any means imply uncommon! Do not disguise your schadenfreude as concern. Do you hear me?”

For a moment his facial expression seemed to oscillate betwixt hostility and supplication.

“Yes, sir,” was all I could muster at the time, as my impromptu investigation was so abruptly brought to a halt. Those ancient oaks, their boughs whispering secrets long forgotten, and Edward’s face – now etched into my mind in a ghastly rictus of silent agony – visit me in restless phantasms, their presence unbidden and unrelenting.

The very next day, the headmaster delivered a brief oration on Mr. Sutcliffe’s outstanding record as a physics teacher – and lamented his early retirement necessitated by unspecified family matters. My fellow pupils reacted to this announcement with a mixture of joy, incredulity, and barely-restrained whispers. I was surprised at the thought that that conversation with Mr. Sutcliffe under the old oaks was likely destined to be our last.

I was left with an unshakeable dread and an ever-recurring question that consumed my every waking thought: what had become of Edward’s mind in those final moments?

In the wake of Edward’s death, I plunged myself into my studies at Oxford with a fervour that bordered on madness. But no matter how deeply I buried myself in the pages of mathematics and philosophy, I could not escape that night. The elegant proofs and equations that had once brought me such joy now seemed mere symbols on a page, unable to penetrate the mysteries of the mind that now obsessed me. I had lost my dearest friend and, in doing so, had lost a part of myself.

It was during one of those sleepless nights, wandering the dimly lit corridors of the Bodleian Library, that I stumbled upon the writings of Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace. Here was a new path, a way to unravel the very mysteries that tormented me. If the mind could be reduced to a series of mechanical processes then perhaps it could be recreated, even brought back?

By the time I had completed my studies at Oxford in the year of our Lord 1891, I had become a man consumed by a singular and most inexorable purpose.

Babbage, the visionary mathematician, conceived of the difference engine and, later, the analytical engine – a machine that, in theory, could perform any mathematical calculation, guided by the uncompromising logic of its mechanisms. And yet, despite his brilliance, Babbage’s work remained unfinished, his dreams unfulfilled.

Ada Lovelace, the brilliant and tragic figure who understood Babbage’s vision more deeply than perhaps even he did, saw beyond the mere calculations. She foresaw a future where such machines could do more than compute – they could create, they could simulate, they could mimic the very processes of thought itself. It was she who penned the first algorithm intended for a machine, making her the world’s first true programmer, a title she would never live to see.

How I yearned to speak with them! What would they make of my obsessions, my relentless pursuit of recreating the human mind through mechanical means? Would they encourage me or caution me against the dark paths my thoughts sometimes wander?

But they are gone, their voices silenced. I am left to walk this path alone, guided only by the echoes of their ideas.

Or so I was led to believe, until my eyes alighted upon a most singular report in the pages of The Times – a discourse upon the endeavours of a young and enigmatic scholar of the Royal College of Science, whose most extraordinary analytical engine had, it was claimed, exhibited such prodigious intellect as to best even Wilhelm Steinitz in the noble game of chess.

The news sent shockwaves through the academic community, igniting heated debates in the parlours and lecture halls across the nation. Could it be that a mere collection of gears and levers had bested the reigning world champion? The very notion seemed to challenge the core of human intellect and prowess.

But the controversy was swift to follow. Sceptics and critics, armed with both reason and incredulity, dissected the event with relentless scrutiny. They questioned the conditions under which the match was conducted, the integrity of the algorithms, and the very possibility of a machine rivalling the strategic depth of Steinitz. It was soon revealed that the result was far from definitive, with accusations of tampering and flaws in the engine’s programming. The victory was ultimately disqualified, the episode dismissed as an elaborate curiosity rather than a genuine triumph. Steinitz’s career remained unscathed, his reputation untarnished, while the young scholar’s work was relegated to the fringes of academic discourse.

Dixon’s analytical engine, a marvel of brass and steel that hummed with almost sinister energy, invited comparisons to a relic of an earlier age, a device that had once captivated the minds of Europe – von Kempelen’s infamous Mechanical Turk.

The Turk, a supposed automaton, astounded audiences by playing a flawless game of chess, defeating even the most skilled opponents. Yet behind its façade of clockwork genius lay a concealed truth: the Turk was no machine of intellect, but rather a clever ruse. Hidden within the wooden cabinet beneath the figure, a human chess master manipulated the pieces, deceiving all who dared to believe in the artificial intelligence of the time.

Whereas the hidden human operator of the Turk was eventually discovered, no such subterfuge could be attributed to Dixon’s device. Still, I could not entirely dismiss the eerie similarities.

Driven by an insatiable curiosity, I penned a letter to Dixon, fully expecting it to go unanswered, lost amidst the daily flood of correspondence that must surely inundate a scholar of his renown.

To my astonishment, he not only replied but extended an invitation for me to join him at the Royal College of Science, to work under his guidance in the heart of London: “I believe your talents will be of great use to me. We have much to discuss.” The prospect was as terrifying as it was thrilling – an opportunity to delve into the unknown and peer into the abyss. How could I refuse?

And so, in the early spring of 1892, I made my way to London to study under this enigmatic man. I did so not just as a scholar eager to learn, but as a man troubled by the past, driven by the desperate need to understand the workings of the human mind.

Leaving Bath was a sorrow I had not fully anticipated. Bath, with its gentle hills and quiet, winding streets, had been my sanctuary for so many years – a place where time seemed to flow more slowly, where the worries of the world were softened by the warm, honey-coloured stone of the buildings and the soothing hum of the River Avon.

But as much as Bath had nurtured me, it was also a place removed from the greater world of academic endeavour – a charming retreat, but one that could not satisfy the growing hunger within me. The libraries of London, the lectures of men like Dixon, and the promise of new discoveries, beckoned me, drawing me away from the safety of my childhood home.

As I stood upon the platform, the chill of the early spring morning seeping through my coat, a strange unease settled over me. The train to London exhaled great plumes of steam. Just as I was about to step aboard, a sudden movement caught my eye – a great eagle, wings outstretched, circling high above the station. For a moment it seemed almost suspended in the grey sky, its sharp gaze fixed upon some unseen target below. Then, without warning, it folded its wings and plunged, a dark blur streaking towards the earth. I lost sight of it beyond the rooftops, but a second later, a sharp cry echoed through the air – brief, final. I shivered, though not from the cold. It was nothing, I told myself. Just the natural order of things. And yet, as I settled into my seat with one last pensive glance at the rolling hills of my beloved Bath, the image lingered in my mind – the predator’s descent, swift and inescapable, a reminder that once a path is chosen, there is no turning back.

Inexplicably, my thoughts turned to Mr. Davis, the venerable purveyor of ices and most singular smoked herring sandwiches, whose modest cart once graced the verdant paths of Royal Victoria Park. Was he still alive and would he remember me after all these years? I carried the memories of home with me, not as a burden but as a question: could the tranquillity I had left behind ever coexist with the ambition that now consumed me? As the train sped towards London, I could not yet know the questions awaiting me – or how deeply they would challenge everything I believed.

Chapter 2: Professor Thomas Minchin Goodeve

Into Paddington Station thundered the locomotive, its iron wheels shrieking in protest as they bit against the rails, the discordant wail sending an involuntary shudder through my very frame. I stepped onto the platform, the cool, damp air of London wrapping around me like a mysterious serpentine beast. The city breathed beneath a veil of coal smoke and mist, each breath carrying the scent of damp stone, soot, and decay.

My destination was the Huxley Building in Kensington, where I was to register as a postgraduate student under Reginald Dixon’s supervision. First, however, I would meet the First Professor of Mathematics, Thomas Minchin Goodeve – a name spoken with reverence in academic circles and associated with not a little awe.

Summoning a Hansom outside the station, I addressed the driver with measured clarity. “To the Huxley Building, Kensington.” The conveyance lurched forward, its wheels rattling upon the uneven flagstones, whilst the gas lamps overhead flickered fitfully, their dim glow contorting the narrow streets into shifting phantasmagoria.

The cab halted before the Huxley Building, an imposing structure of burly red brick and terracotta. Its neoclassical design, crowned with Corinthian columns and tall, arched windows, exuded intellectual authority.

Within, the grandeur of the edifice was near oppressive: endless marble corridors unfurled before me whilst lofty ceilings, adorned with baroque embellishments, bore down as though heavy with the burden of centuries of accumulated wisdom. The air was thick with the scent of ink and paper, mingled with the faint tang of coal smoke from the gas lamps flickering along the hallways.

The Huxley Building formed part of the Royal College of Science, a fledgling institution that sought to rival the world’s leading centres of scientific education, drawing luminaries like Thomas Minchin Goodeve to its fold.

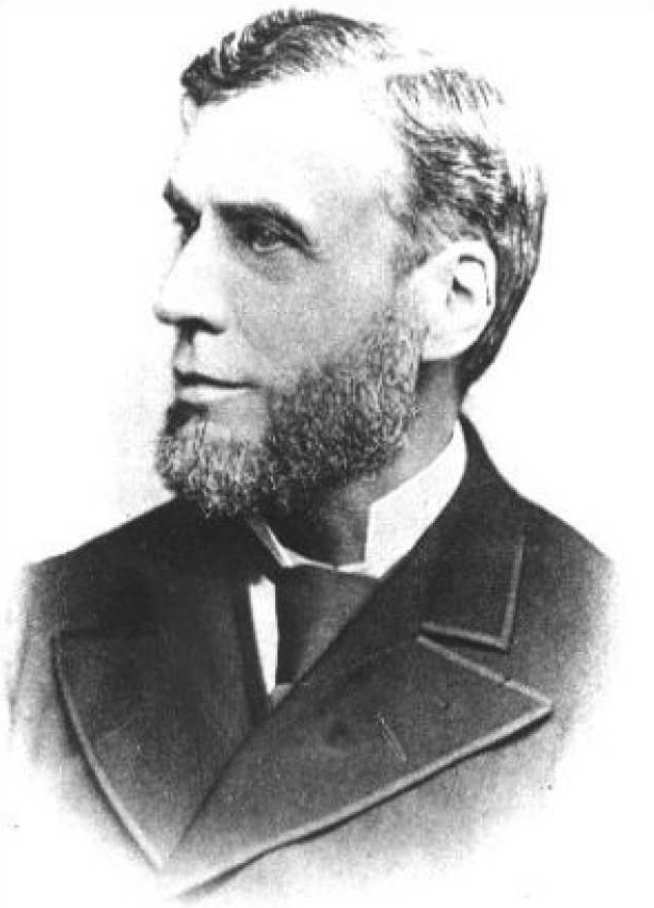

Professor Goodeve’s reputation was already the stuff of academic lore. A scholar of Wadham College, Oxford, he had indelibly altered the course of mechanical engineering with his magnum opus, The Elements of Mechanism, a treatise whose insights had left an indelible mark upon my own studies. As the First Professor at the Royal College of Science, he had shaped the institution’s direction, forging its reputation as a hub of industrial and scientific innovation.

I found his office easily, a small plaque bearing his name on the heavy oak door. When I knocked, a firm voice called me in. Professor Goodeve was seated behind a cluttered desk, his piercing gaze meeting mine as I entered. He stood, offering a handshake that was both courteous and deliberate.

“Mr. White, I presume,” he said. “Welcome to the Royal College of Science. I trust your journey was uneventful?”

“It was,” I replied, though my thoughts betrayed my apprehension. “I’m honoured to be here, Professor.”

He nodded, his expression thoughtful.

“Mr. White, before we proceed, I am keen to understand something,” he began, his voice carrying a mix of curiosity and sternness. “What motivates you to pursue a path in science and mathematics? This is not merely an academic question – I am genuinely interested in what drives my students.”

I hesitated but a moment, gathering my thoughts ere I ventured to reply. “Well, Professor, I believe that advancing our understanding of science and mathematics is essential for the benefit of the Empire. It can lead to technological progress that strengthens our industrial capabilities and global standing. Scientia imperii decus et tutamen.”

Professor Goodeve’s eyebrows arched slightly and he leaned back in his chair, fingers steepled, his eyes sharp with scrutiny. “Indeed, those are commendable goals, Mr. White. But they sound rather…impersonal. Is there nothing more personal driving your quest for knowledge in these fields?”

His question caught me off guard and for a moment I struggled to maintain eye contact. My voice was softer when I finally responded. “To be honest, Professor, my interest in science…it’s a deeply personal crusade. It’s the lens through which I make sense of the world. It’s not just about the Empire’s progress or societal benefits – it’s about satisfying an inner compulsion to understand the mysteries of the universe. It’s…it’s how I connect with everything around me.”

Professor Goodeve studied me for a long moment, his expression softening. “Ah, there it is,” he murmured, as though in quiet communion with some unseen presence. “The veritable spark. That is what truly drives a scientist, Mr. White. Never lose sight of that personal connection to your work – it will guide you far more faithfully than any external ambition.”

I nodded, feeling a weight lift from my shoulders. It seemed I had passed an unspoken test, and with Professor Goodeve’s subtle nod of approval I felt more confident in the path I had chosen.

Goodeve paused once again, as if sizing me up. An uncomfortable silence ensued. I broke eye contact with him as my eyes caught sight of an old copy of The Times buried among the scientific manuscripts obscuring most of Goodeve’s enormous mahogany desk. “Louis Le Prince vanishes in Dijon.”

Louis Le Prince? Of course! A Frenchman, the first person to shoot a moving picture sequence using a carefully constructed camera and a strip of paper film. His work culminated in 1888 with his motion-picture experiments in Leeds. Then he abruptly left England, returned to France, and was declared missing in Dijon two years ago. Newspapers implicated the involvement of secret societies, one or two of which counted Le Prince among their ranks, often under the mysterious nom de guerre Brother Lamed.

Goodeve finally spoke again: “Reginald Dixon is a remarkable man – brilliant, yes, but unconventional. His methods demand scrutiny. Brilliance and obsession often walk hand in hand, Mr. White. Some men do not recognise when they have crossed the threshold. As they say, listen, observe, and be silent when needed. You’ll learn far more that way.”

I absorbed his advice with a nod, understanding the weight of his caution. It was clear that working under Dixon would not be a typical academic experience, but rather one that might challenge every preconceived notion I held about the scientific world.

“Thank you, Professor,” I said earnestly. “I appreciate your guidance and will take it to heart.”

Professor Goodeve smiled, a rare softening of his otherwise stern demeanour. “Very good, Mr. White. I expect great things from you. Do keep me informed of your progress.”

With that, he extended his hand once more, signalling the end of our meeting. I shook his hand, feeling the firm grip of a man who had moulded many young minds, and left his office with a new sense of purpose and a keen anticipation of the challenges that lay ahead.

Not until I had departed his study did the gravity of his words descend upon me with full force. I sensed that my role would extend beyond that of a student. I walked down the hall with a mix of anticipation and unease. The echoes of his words – was it advice or a warning? – lingered in my mind, leaving behind a sense of unease I could not yet name.

As I rounded the corner, I was nearly thrust off my feet by a sudden collision with a young man. Despite the abruptness of the encounter, I managed to maintain my balance, whilst the young man was not so fortunate and fell to the ground. With a hasty admonition for me to watch my steps, he quickly regained his footing, picked up his spectacles, adjusted his ginger hair, and dashed into a nearby lecture room.

Moved by a surge of curiosity and an unbidden desire to learn what hastened his hurried departure, I stealthily approached the door he had entered, which he’d left ajar. There, with the utmost discretion, I leant my ear to the proceedings within, my interest piqued by the animated discourse that flowed from the room. I heard the lecturer’s voice:

“Ladies and gentlemen, today we shall delve into the art of cryptography, a subject of considerable import in both our diplomatic and military spheres. We stand upon centuries of scholarly effort to conceal and reveal secret messages, an endeavour that has evolved from the simple ciphers of antiquity to the more sophisticated methods we observe today.”

That the learned minds of this institution should occupy themselves with the arcane science of cryptography was, perhaps, to be expected – for what discipline could better serve both the cause of war and the quiet intrigues of diplomacy? Yet here, within these very halls, its presence suggested deeper currents unseen. What clandestine machinations, I wondered, lurked beneath the scholarly veneer?

“Firstly, we discuss the substitution cipher. In its simplest form, one might take each letter of our message and shift it a certain number of places in the alphabet, a technique popularised by Julius Caesar, hence its nomenclature, the Caesar cipher. Yet one may also adopt more intricate schemes, substituting entire sequences of letters based on more elaborate rules and keys.

“We then come to the Vigenère cipher, a more refined encryption method employing a series of interrelated Caesar ciphers based on the letters of a keyword. This polyalphabetic system has, for a time, earned the reputation of being inscrutable, or le chiffre indéchiffrable.”

I nearly tumbled to the floor when the ginger-haired head of the same scholar extended the aperture that I used to eavesdrop on the lecture and sized me up with cold watery eyes. Without saying a word, he thrust the door shut and locked it from inside.

I felt a peculiar chill run down my spine as I dashed to the exit.

To be continued…

Read on Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.com

Comments are closed.

2 Comments.

What a cool story!

You’ve crafted a masterful piece of historical fiction. The writing is incredibly immersive, drawing the reader into the late-Victorian era with rich, evocative prose that feels both authentic and compelling. The strongest element is the atmosphere you’ve built. The contrast between the tranquil Bath and the grim, smoky London sets a perfect stage for a mystery that blends a personal tragedy with a larger historical conspiracy. I was particularly captivated by the blend of real historical figures (Babbage, Lovelace, Jack the Ripper) with the fictional narrative. It’s a clever way to blur the line between fact and fiction, making the story feel both grand in scale and deeply personal. The characters, especially the narrator, Paul Gordon James, are intriguing. His motivation, born from the tragic loss of his friend Edward, provides a strong emotional core. The enigmatic warnings from Professor Goodeve and the mysterious nature of Professor Dixon’s work hint at a much deeper conspiracy, leaving the reader eager for more. The prose is a huge strength, but it’s worth noting that the long-winded disclaimer at the beginning and the occasionally dense descriptions could slow down some readers. However, for a fan of the genre, the payoff is well worth it. This is a highly promising start to a novel. It has all the elements of a classic gothic mystery, an intellectual thriller, and a hint of something more sinister and modern lurking beneath the surface. I’m hooked and want to know what happens next!