Marina 2.0: A Life Rebuilt from Scratch

“In December 2020, I fell and broke my neck,” says Marina Logacheva with a light smile, then adds dryly: “A perfect way to start the new year.”

“In December 2020, I fell and broke my neck,” says Marina Logacheva with a light smile, then adds dryly: “A perfect way to start the new year.”

That’s how the story begins — of a woman for whom 2020 became a zero point, the start of a new life where every morning requires meticulous planning, and every ordinary act demands dozens of small, daily efforts.

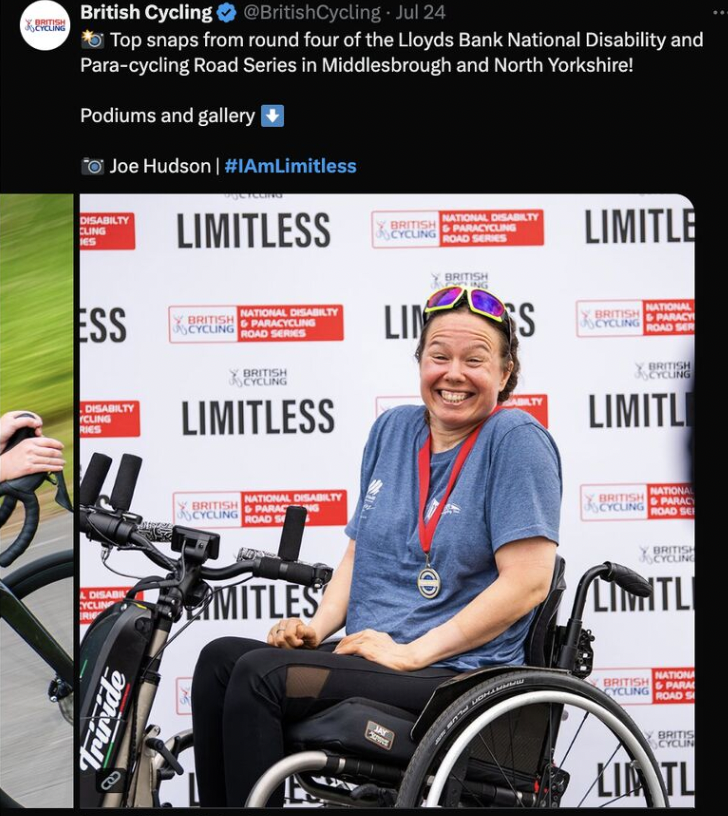

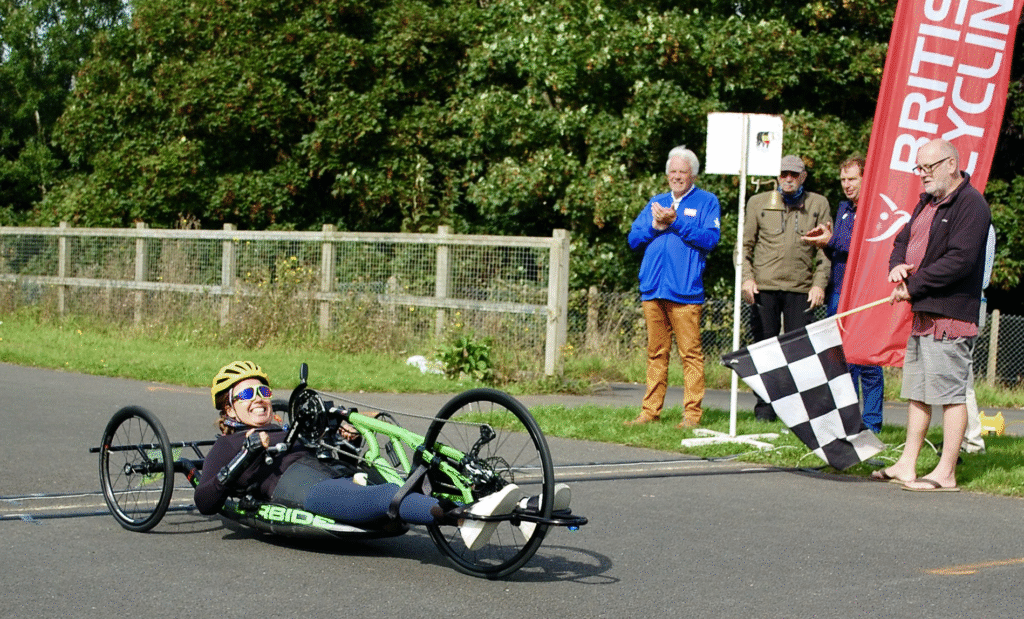

This isn’t a tale of “heroic triumph,” but a chronicle of adaptation — often painful, sometimes ironic. It’s the story of Marina 2.0, who went on to win bronze at the Para-Cycling World Championships.

“I’m five years old now” — and a body that no longer belongs to you

Marina speaks about her injury without pathos or bitterness — as if it were simply a fact of life. The medical diagnosis was concise: a high spinal cord injury. For her, it meant one thing — a complete redefinition of what’s possible.

“My hands don’t work well, my legs don’t move at all,” she explains. “I can’t go to the bathroom on my own, get dressed, take a shower, or cook.”

The first few months after surgery were literally a reboot. Because of the tracheostomy tube in her neck, she had to learn to breathe, speak, move her hands, and write all over again. “I was like a little child,” she says. “That’s why I call myself Marina 2.0. Technically, I’m five years old now.”

The hardest part, she admits, isn’t pain or immobility, but the loss of control over her own body. “Your body doesn’t belong to you anymore. It lives its own life. It might want to use the toilet — or not. You can’t plan what will happen to you even five minutes ahead.”

This unpredictability makes daily life fragile. Simple things — a shower, coffee with friends, a short trip — turn into logistical operations involving phone calls, checks, and coordination. What once took thirty minutes can now consume an entire day.

Not rehabilitation — adaptation

Marina dislikes the word rehabilitation. “It implies returning to what you were before. But what if that version of you no longer exists?”

Instead, she speaks of adaptation. “If your leg has been amputated, you can’t go back to your old paradigm — but you can find new functions. It’s not recovery; it’s reconstruction. You can’t ‘get your body back.’ You can only learn to live with the new one.”

For Marina, adaptation is not just physiological. It’s a reconfigured everyday life, a new system of coordinates, new relationships with time and with people. Everything — from the body to work, communication, even pace — had to be rebuilt from zero.

(In)dependence and a new kind of freedom

Before the injury, Marina lived fast: she worked in marketing, ran marathons, and completed a full Ironman — one of the toughest triathlons in the world.

After the injury, her movements became deliberate, cautious, and dependent on another person’s assistance.

“There’s always someone else in my apartment,” she says. “Not a friend or a partner, but an assistant who helps with literally everything — from showering to going out.”

At first, the constant presence of a stranger in her private space felt almost unbearable — and often still does. “What I miss most isn’t movement, but solitude,” Marina admits. “I dream of spending just one day completely alone. But I still don’t know how to make that happen.”

Over time, she realised that dependence doesn’t cancel out freedom — it simply takes a different form. “I had to learn to accept help without losing autonomy. To be dependent — and still be independent.”

When every morning is a project

Marina’s daily life runs with mathematical precision. “The toilet doesn’t take two minutes — it takes twenty. Multiply that, and you’ve got two and a half hours a day just for that. Add showering, dressing, travel — and several hours are gone doing what used to take one,” she says.

Spontaneity has become an impossible luxury. She used to be able to wake up on a Saturday, buy a ticket, and fly somewhere just because she felt like it. Now even a simple café visit demands calculation: assistant, transport, accessible toilet, ramp.

“That’s why I’ve learned to choose myself,” Marina says. “If I’m tired, I say no. I take a day and just sleep. That’s a new skill.”

Three jobs and a £16,000 bike

After the injury, Marina didn’t cut back on work — she doubled down. Today she juggles three roles.

Firstly, she is the Disability Sport Lead at the sports marketing agency MATTA (makeitmatta.com), where she works with federations and brands to promote adaptive sports and help include people with disabilities in campaigns.

Secondly, she is a marketing specialist at the charity REGAIN SPORTS CHARITY (regainsportscharity.com), which helps people with tetraplegia return to sports.

And finally, she is the co-founder of the adaptive clothing brand FAST (fastadaptivefashion.com), created together with her friend Daria Tafintseva. “Ordinary clothes aren’t comfortable when you spend your day sitting down. We made something you can actually live in — not just pose for photos,” Marina explains.

In Russia, her brand has already been added to the list of official government suppliers. “It’s still more of an expensive hobby for now,” she laughs. “But an important one.”

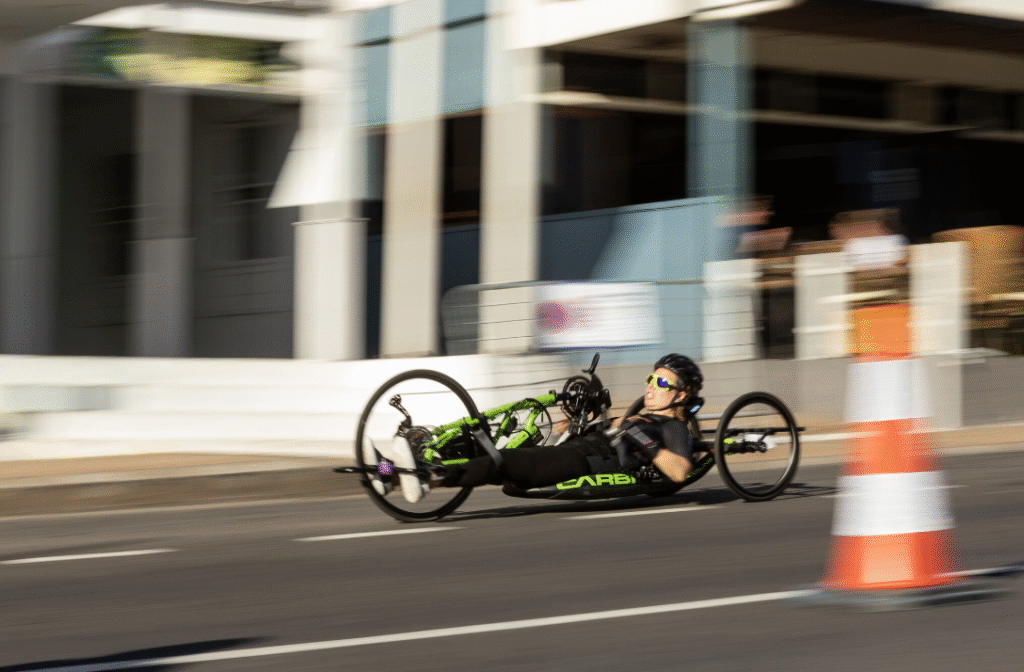

And then there’s cycling. “For me, sport is like food and air — without it, I’d just get stuck.”

Her handbike costs £16,000, gloves £3,000, wheelchair £6,000, electric attachment £7,000, and the adapted car she drives — £20,000. “It’s not luxury,” she clarifies. “It’s the price of simply being able to move.”

These aren’t “premium” items but specialised equipment — their “normal” counterparts would cost ten times less. Those figures are worth remembering when people debate “benefits” and “social support.”

Laughing, Marina calls her bike “a Škoda among Ferraris — but it goes, and that’s what matters.” (Worth noting: she’s a World Championship bronze medalist in para-cycling.)

A story about a single step

“When people ask whether sport in Britain is accessible to people with disabilities, I have a story,” Marina says.

Once, she signed up at a local gym — but couldn’t get inside. There was a step at the entrance and no ramp. She wrote to customer support and received this reply: ‘Go to a different gym.’

“It took me three months to get a refund for the membership,” she recalls. “In the end, after I threatened to sue, they apologised, offered three months free, and a personal trainer. But that’s just one gym.”

It’s those small things — steps, broken lifts, lack of toilets — that create systemic barriers excluding disabled people from entire areas of life.

Recently, Marina won a Churchill Fellowship, a grant to travel to Australia, the U.S., and Canada to study inclusivity in sport. Afterward, she plans to work with UK Active, the regulatory body for British gyms, to develop accessibility guidelines — so that inclusion becomes the norm, not a battle fought “one step at a time.”

Superhuman, Team GB, and the right to be ordinary

British media often call disabled athletes superhumans. Marina finds the term grating. “I’m glad if I inspire someone,” she says, “but I’m not a superhuman. I’m just a person who drinks coffee, buys flowers, and goes out for milk. That can be enough.”

Her view is simple: “Why should every disabled person have to be a Paralympian? Not every non-disabled person is an Olympian. Sometimes you just want to live.”

That said, Marina still plans to pursue her athletic career. She dreams of joining Team GB and competing at the Paralympics — though, as she notes, that takes years and serious funding.

If that doesn’t work out, she hopes to set a Guinness World Record as the first woman with a broken neck to complete a full Ironman triathlon.

Marina 2.0: Epilogue

Listening to Marina, you realise her story isn’t about victory or defeat. It’s about life that continues — even when everything changes: body, rhythm, rules, the world itself.

Marina doesn’t try to look strong, nor does she pretend to be weak. She just lives — with all the complications, pauses, and logistics that now fill her days, where every action requires preparation, and every joy — effort.

“I want the world to be a bit easier for those who already have it hard,” she says. “So we don’t have to prove every day that we have the right to simply live.”

And that, perhaps, is the essence of Marina 2.0 — not to be a role model, but to be herself. Not to inspire, but to exist — fully, stubbornly, and genuinely.