‘The Last Train’: Art on the Threshold of Emigration

‘The Last Train’, held from 19 to 22 November in the Old Waiting Room at Peckham Rye station, was one of those rare exhibitions where a venue doesn’t merely contain the art but enters into dialogue with it.

Built in 1865 by Charles Henry Driver, the waiting room—with its high wooden vault resembling an overturned ship’s hull—offers only temporary shelter, embodying the very condition of “in-between,” so familiar to an emigrant: neither here nor there, but standing on a threshold.

The space strikes the viewer almost physically: fragments of old paint like layers of memory; the rhythm of arches running along the walls like alternating destinies; and the muffled noise of passing trains appearing suddenly, then vanishing. All of this forms a unified backdrop of collective experience, where forced emigration and its causes cease to be private biography and become a shared cultural condition for the fifteen exhibiting artists, emigrants from Russia, Iran, and Turkey.

It was in this very space that artist and curator Sima Vassilieva conceived the idea for The Last Train a year ago. One of the starting points was Konstantin Benkovich’s sculpture The Suitcase (2023): a suitcase made of rebar, painted blue, a symbol of any forced journey. Emigration, the work suggests, is not merely relocation, it is the transport of one’s cage and unfreedom.

Another dimension of the concept is provided by Pavel Otdelnov’s painting Cargo 200 (2022). The refrigerated railcar carrying the bodies of fallen soldiers reflects the terrifying reality of war, when the last train may be precisely such a railcar, and an emigrant’s fate becomes the final chance to save one’s own and others’ lives. Valya Korabelnikova’s photograph—lit candles against the sea, framed by a black window—transforms the space into a temple for each viewer, where the ritual of mourning becomes a way of experiencing war and personal grief (Mourning the Fallen in War, 2025).

The viewer is immediately drawn into an open conversation: at the entrance to the hall, a flag by the Pomidor Duo group hangs from the railing, asking: “What would you do in my place?” (What Would You Do?, 2023)—a gesture of both vulnerability and challenge, speaking of the difficulty of choice, the price of free speech, and resistance to censorship and propaganda.

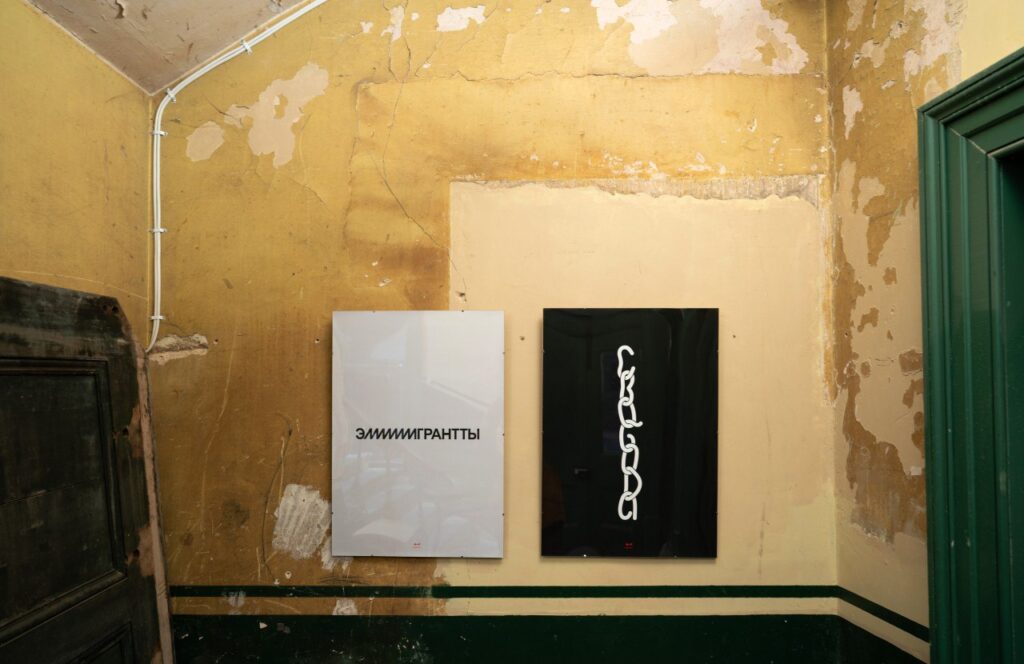

Artist KUNGFUCT responds to this challenge with uncompromising directness: his posters Freedom, Emigrations (2025) frame emigration as an act of liberation. Sergey Novikov’s photographs, printed using archival methods, record portraits and migrant routes as a topography of exiles. One of the works inevitably recalls Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer, but in a different register: not a sublime hero above nature, but a migrant trapped between geography and politics, standing alone with modest belongings before a border fence, beyond which a beautiful snow-capped peak of another country glimmers faintly through the trees (Relocation, 2023). Kindergarten (2024)—another of Otdelnov’s works at the exhibition—addresses childhood memories turned by the post-Soviet era into ruins of memory.

Katya Granova’s painting reflects on propaganda and the rift that has split many families, poisoning even the closest relationships with political divides (Grandma Swetlana reading her speech, 2022). Both works demonstrate the artists’ ability to treat memory as material, merging the documentary nature of photography with the subjective gesture of painting. These large-format pieces, immersed in ochre-ashen and blue tones, become the visual axis of the exhibition, binding the space and the other works through colour and form.

Sima Vassilieva’s Blue Wagon (2025) installation—a girl and the Cheburashka toy at the window of the “Moscow–Chop” train—refers to the experience of Soviet emigration, overlaying historical optics onto the present. After all, Cheburashka, the friendly fictional character from a popular Soviet animated film, is essentially an emigrant who arrived in a foreign land in a crate of oranges and had to adapt.

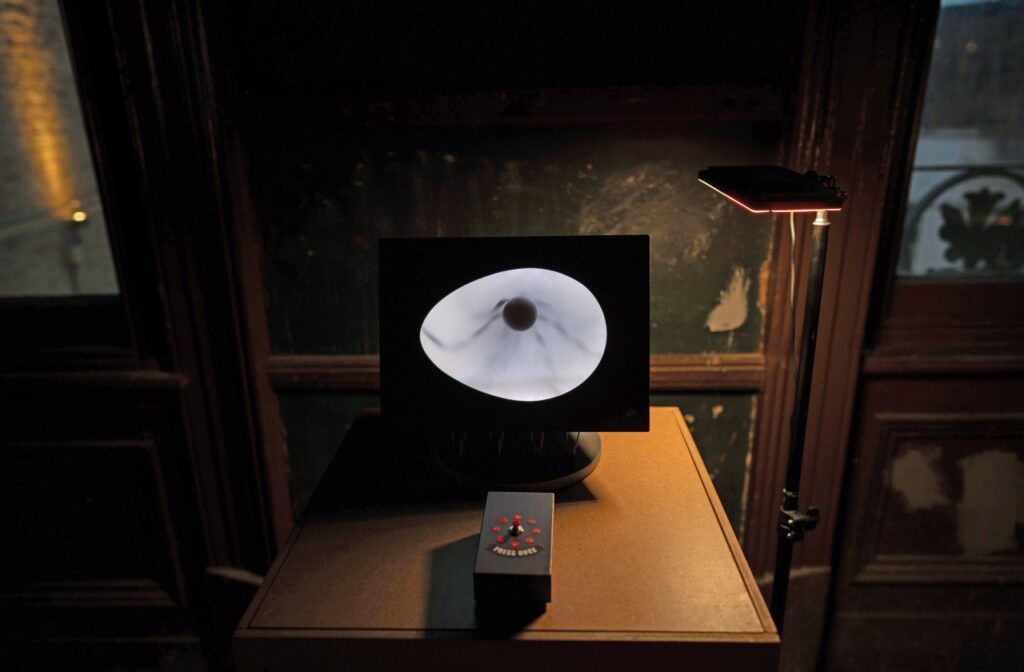

In cultural memory, the “Blue Wagon” song became an allegory of Jewish emigration from the USSR and the idea that freedom was a scarce resource for which people fought. The artist also speaks about the “genetic” memory of generations forced to leave their homes to escape war and ideology. In this context, one of the key statements of the exhibition comes from the work of Sasan Sahafi, an artist from Iran, who explores the tension between the individual and society, reflecting on external, but above all internal unfreedom (Tension 1/1, 2021).

Ekaterina Belukhina’s cement totems—heavy, as though formed from accumulated memories of relocations and abandoned things (Transient Monuments, 2025)—resonate with this theme. Turkish artist Sila Sen offers her own version of a museum of losses: a miniature openwork pavilion woven from wire, composed of what has been lost and left behind. She suggests that forgotten objects that we abandon also deserve a new life (Lost Property Office, 2021).

Alexander Tarasenko’s piercing sculpture—a figure modelled after the artist’s own body, impaled on a needle like an insect—holds a special place in the exhibition. The work explores cultural shock, symbolic death, and the possibility—or impossibility—of rebirth and adaptation in a new cultural environment (The Green Lizard Boy, 2025).

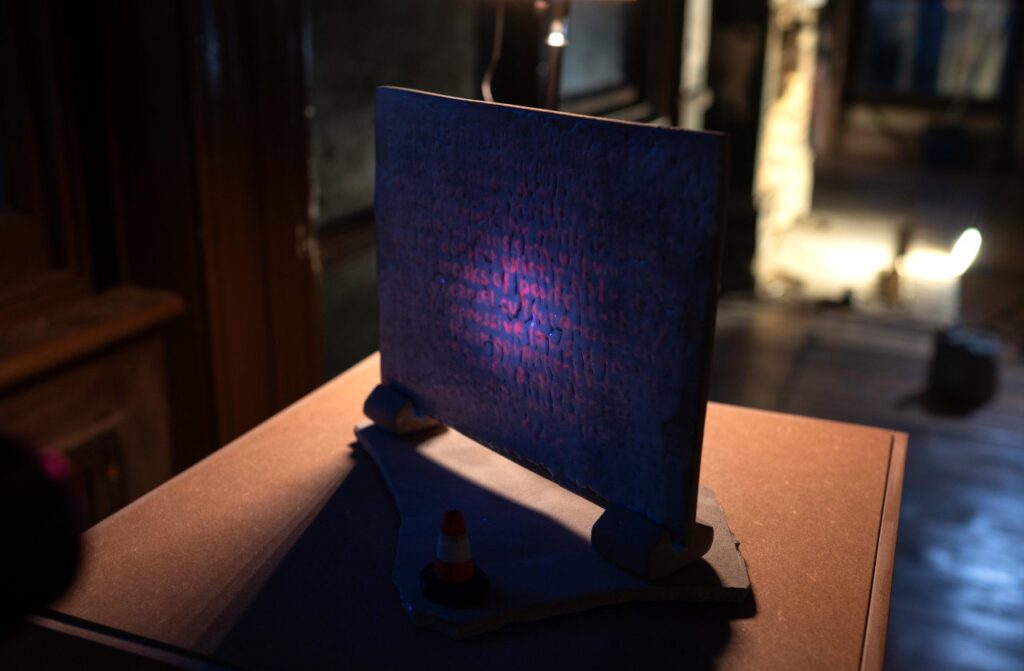

Olesya Ilenok reflects on the same theme. Her ceramic sculptural group is a double-sided work: on one side, a blank wall patched with layers of paint; on the other, faintly emerging text and phrases speak of the impossibility of explaining oneself, of hidden thoughts and conversations we carry within (Hidden Conversations, 2025).

In Polina Egorushkina’s lyrical watercolours, emigration appears as a fragile dream: a vision of a beautiful misty landscape or a heavy gloom from which there is no awakening (Somewhere, The Sleeper, 2023). Kirill Basalaev’s painting resembles a painterly ruin, where cracks and layers preserve traces of the past while allowing for something new to emerge (The Retention of Memory, 2023).

At this point, exhibition and architecture fuse into a single statement. The Old Waiting Room is not merely a backdrop but a fabric woven into the overall meaning: it affirms that “the last train” is not only a chance for salvation and renewal, but also a drama, a moment of pause on the threshold, where a person confronts choice, freedom, war, and memory.