This autumn the famous theatre and opera director Kirill Serebrennikov made his directorial debut at the Paris Opera House. It was also the debut appearance at Opera de Paris for all the members of his creative team (designer Olga Pavlyuk, costume designer Tatiana Dolmatovskaya, video designer Alan Mandelstam, choreographer Evgeny Kulagin and dramaturge Daniil Orlov). The director invited those who worked with him at Gogol Center in Moscow, on Platforma projects, and later at Avignon Festival (“The Black Monk”) and in opera productions at various venues around the world. The musical part of the opera featured the experienced British conductor Alexander Soddy and a group of star soloists: the exquisite Polish tenor Piotr Beczala as Lohengrin, baritone Wolfgang Koch as Friedrich of Telramund, Korean bass Kwanchul Yoon as Henry the Fowler and two magnificent mezzo-sopranos, Ekaterina Gubanova and Nina Stemme, alternating in the role of Ortrud. This excellent cast also included two female newcomers in the role of Elsa – soprano Johannie van Oostrum (South Africa) and Irish singer Sinead Campbell-Wallace.

A traumatic experience: Kirill Serebrennikov makes his debut at the Paris Opera

Serebrennikov decided to make the traumatic experience that war brings the focal point of his production. In the interview featured in the Lohengrin leaflet, dramaturge Daniil Orlov discusses the similarities between the German word “traum” (a dream) with the word “trauma”, and explains why a post-traumatic syndrome becomes the key to this production. Serebrennikov himself says that in Wagner all the positive characters (the King and Lohengrin himself) have either returned from war or are about to lead an army on a campaign, while the bad characters (Friedrich and Ortrud) are doing everything to stop the warfare. Kirill Serebrennikov decided to reveal and expose this inconsistency in his new production.

Lohengrin’s scenography embodies the division of the world into fragments characteristic of a traumatised mind – the stage, as designed by Olga Pavlyuk and lighting designer Frank Evin, is sometimes divided vertically into three spaces (left, right, and centre), and sometimes also has an additional horizontal division, splitting the set into two long parts. We can thus simultaneously observe video reels on three screens above and the action in two or three spaces below, with the need to follow different proceedings in five or six fragments of the stage. These fragments are connected only when viewers manage to immerse themselves in black-and-white videos of Gottfried the soldier (the visions that Elsa has of him are haunting memories of his departure and dreams of his actual warfare) and Elsa scurrying around the empty, dilapidated room, which become the semantic dominant point of this opera. The scene becomes a metaphor for the split of our consciousness and the world around us.

Quite forcefully twisting Eschenbach’s epic of Parsifal that was one of the sources of Wagner’s libretto, Serebrennikov, as we can see from the very beginning, based his work on the idea of the destructive power of war and the impossibility of peace and universal happiness when even one individual ming is destroyed. A tear even of one child should not be spilled, as Dostoevsky put it, and in this production Elsa steps up as such a mad, traumatised kid. Serebrennikov shifts the semantic focus of the production so that Elsa’s expectation of a saviour that is crucial for Wagner’s libretto, and Lohengrin’s mysterious identity cease to serve as pivotal points of reference but turn out to be false clues, fantasies that destroy the world.

Or rather, they aggravate its condition, because the world has already been destroyed by the departure of Elsa’s brother Gottfried to war. It is his departure and potential death that Serebrennikov pressures upon us in showing throughout the opera that the return of this ‘swan-like’’ brother is virtually impossible. In Alan Mandelstam’s video, we see a young man in the trenches, wearing a helmet, and carrying a rifle – dusty, killing, running, and angry – and those are definitely visions seen by Elsa, her traumatised ‘traums’. She flounders and finds no way out of her fantasy, turning into a phantom of herself in the video as much as on stage. She lives for us, the viewers, in a world of colour, but in her own consciousness she survives only in black and white, next to Gottfried, who has been revived by her memory. Elsa is torn to pieces not only mentally, but also physically, as on stage there are two actresses, besides the singer, who have exactly the same red hair and move in mermaid dances with crooked legs and arms. They, similarly to Elsa, later find themselves in a ward for the mentally ill, shaved and disorientated, continuing their ghost-like movements in the claustrophobic place of a medical room.

What are the roles allocated by Serebrennikov to other characters of Wagner’s opera? In this production, Ortrud (Nina Stemme) and Friedrich of Telramund (Wolfgang Koch) are either the owners of a hospital for the mentally ill or the attending physicians. Ortrude appears in a doctor’s gown and gives instructions to her nurses. Judging by the scenes with Telramund, he is also tormented by mental anguish of unknown origin. Perhaps, according to this conception, suffering from yet another post-traumatic syndrome) and is almost ready to die, which is what indeed is supposed to happen later in the plot. It is not Lohengrin who kills him (who, despite Peter Becala’s outstanding performance, is just a ghost here), but his own inner breakdown, which has undermined him irrevocably, quite similarly to Elsa. Something is rotten in the state of Denmark, and, according to the director’s vision, there is no hope for a cure.

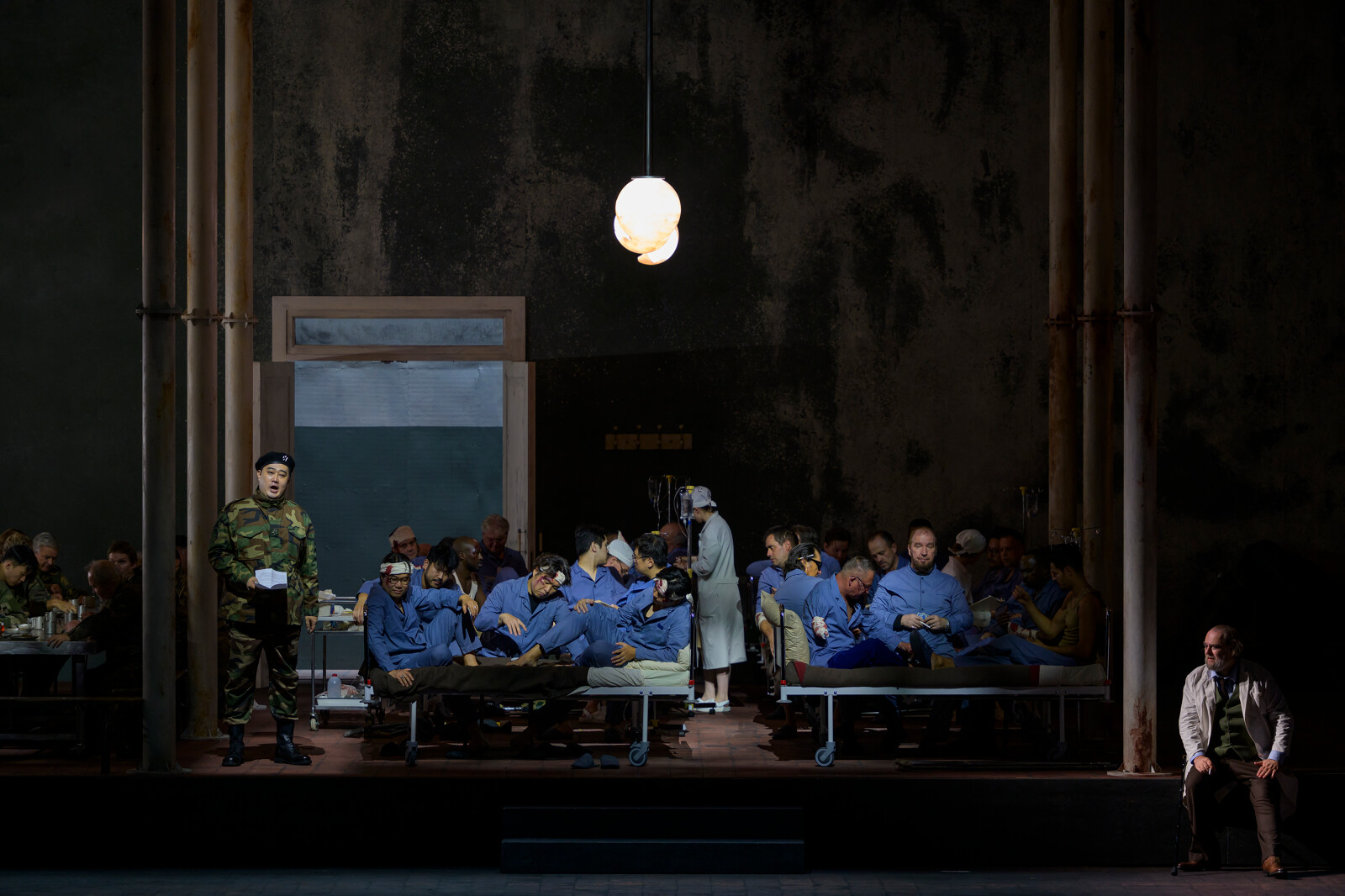

In one of the closing scenes where Lohengrin talks at length about his life story, he is surrounded by chorus soloists – wounded soldiers recovering in this hospital. In Serebrennikov’s interpretation, Lohengrin turns out to be the greatest evil created by our consciousness. He represents the artificial image we create to replace the reality of life, he is the mask we wear not to look it in the face. Lohengrin, whose name is unknown, is a dream of unambiguity, strength, light, clarity, transparence of a world where “the ceiling is white, the boots are black, the sugar is sweet,” as the bourgeois Lebedev said in Chekhov’s Ivanov, where someone from above can come and save everyone. It is precisely such a dream of a beautiful and understandable world against the backdrop of an increasingly self-absorbed madness and trauma that is rejected and publicly flogged by Kirill Serebrennikov.

But what about the music, the Wagnerian plot, Wagner’s libretto? They somehow exist in a separate space and cannot keep up with the flow of visual metaphors that the director is throwing on us. If you accept Serebrennikov’s concept, it is so aggressive that its meaning becomes clear from the scenes where three Elsas spin around in three different spaces, and the young man of her dreams disappears somewhere in the distance with a military backsack. If you don’t accept it, you are not given the opportunity within this stage concept to enjoy the acting and vocal work of Petr Bechala, Kwanchul Yoon, and other outstanding performers. In this production the women come to the forefront – Johanny van Oostrum as Elsa and Nina Stemme as Otrud are always in the centre of our attention. The opera is first and foremost about their conflict, where Elsa represents the world of the traumatised mind and Ortruda is the one who wants to save her. But Wagner’s music has certain musical characteristics for Otruda – it is her revenge (she asks for vengeance before she speaks to Elsa) that is central to her, it is a dark desire to deceive and destroy purity, to provoke the heroine into an act that will lead her to her doom. The director’s conception cannot change the music, and Nina Stemme’s heroine does not make a pure and luminous “healer” whatever she might do on stage – her clinic becomes a gloomy, scary place where, apparently, they break bones in order to heal the time that is out of joint.

Rearranging Wagnerian meanings and changing plus for minus cannot do anything with the music, which is performed by Alexander Soddy’s orchestra splendidly, fantastically, with precise dynamics and rhythms and attention to singers. How can one listen to such a disjointed opera, where music goes one way and its visual concept some other way? How not to come out of it with a mind as split as that of the characters’? How not to fall into the schizophrenia of the music’s divergence from the director’s strong concept? No answers are provided. If this instability and displacement was the effect that Serebrennikov and his team wanted to achieve, this goal has definitely been achieved. You leave the opera in a strange, eerie, by no means uplifting mood. Watching it again will be too painful and traumatic. If this is an attempt to take the viewers out of their comfort zone, it is indeed effective. Serebrennikov deliberately offers no solutions. Or, perhaps, only this: we should cast aside our camouflage of beauty and look into the eyes of those numerous phantoms, open those locked rooms that we have created while deliberately fleeing from the world in conflict.