Alexander Molochnikov: “How can you forbid creating something simply beautiful?”

Alexander Molochnikov is one of the most prominent young directors in contemporary theater and cinema. His productions have always sparked discussion. After emigrating to the U.S., he staged a successful sold-out play — and now he is bringing it to London.

– You’re bringing your play The Seagull: A True Story to London, after it sold out at the Ellen Stewart Theatre in New York. In London you’ll be performing at the Marylebone Theatre — how do you like the venue?

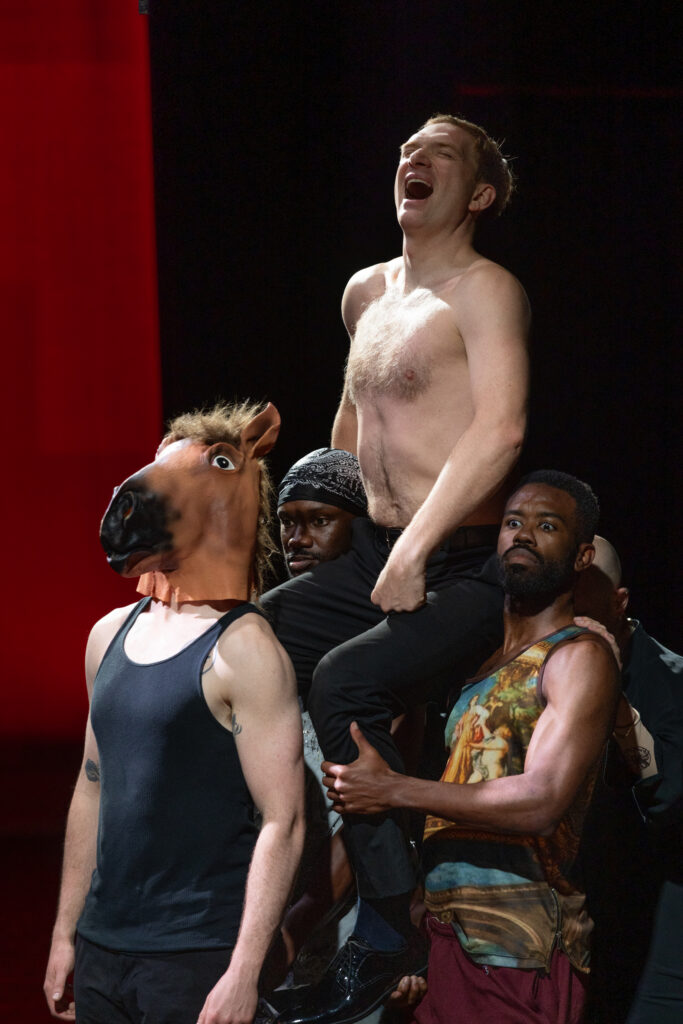

– It’s a good space. Our play is “red,” so we want to lay out some kind of red carpet from the entrance, like a blood vessel, leading straight into the heart of our show at Marylebone. I hope the audience comes to see us the same way they did in New York!

– You’re used to sold-out shows!

– I remember when we performed in Moscow at the Yauza Theatre — that’s way out past the Third Ring Road — and we had packed houses, everything was great, and the whole cultural elite showed up.

– Why does The Seagull have a subtitle?

– Our Seagull is not Chekhov’s Seagull; we only take it as a starting point. It’s a play about a young director who wants to stage The Seagull in a Moscow theater in 2022.

– After the war had already begun?

– He wants to stage it before, but the war begins during rehearsals, just before the premiere.

So they force him to remake the whole production, to remove everything free and contradictory. And nothing is left.

I was rehearsing this show in the States, where, for various reasons, it’s very hard to make exactly what you want. We worked on The Seagull: A True Story for several years. That is, before the war, after the war began, under Biden, and under Trump. These were four very different cultural vectors, so to speak.

In fact, I believe that despite everything, before the war Russia had a very free theatrical space, extremely tolerant. That becomes especially clear now, when you compare it to what you see around you. Then I encountered the American space — pre-Trump, leftist. And now there’s another turn, some kind of reorientation, frankly not so clear. Here’s a small spoiler: at the beginning of The Seagull, the characters advise each other not to mention they’re from Russia, and at the end they say, “You can say it now, we live in a very good world, a very good world,” as the president says.

– What’s difficult about these cultural vectors?

– Restrictions. Not only in the political agenda, from angry deputies or Mizulina-types. They’re also in the cultural sphere’s interest in what you’re doing. In the ability to get funding, to push a project through the jungle of rules in that community. In finding a theater. In finding actors willing to work with you. And of course, in ethical questions as well.

– To what extent can, should, or must an artist respond to the world around them — political, social — and how much should they reflect that in their art?

– Nobody owes anyone anything!

– I often hear the opposite.

– But by debating with those who say that, you automatically enter into a sort of bargaining. No one owes anyone anything, I really believe that. What did Monet owe anyone when he painted his water lilies? What did Pissarro owe? What did Van Gogh owe when he painted the same landscape over and over from his window?

Of course Shostakovich reflected reality. But Chopin — not always.

How can you forbid someone from creating something simply beautiful?

I think since February 2022, not just theoretically but practically, we’ve come to understand that everything has become truly tangled, truly complicated. It’s ambiguous. I don’t mean Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — that’s unambiguous. But the world as a whole has become confusing. And sometimes, someone who simply creates something beautiful, distracting people from grief for a little while, may be doing something more useful than political films. I say this as a director of political films and political plays.

So, on the one hand, I believe no one owes anything. On the other, when people say “art is outside politics,” I don’t see where politics begins and ends. Obvious question: is war politics or not? Is a bomb falling on you politics or not? Yes, it’s politics. But it’s also a bomb that kills your mother. And yet you’re “outside politics”? We’ve seen in recent years that there’s no clear boundary. They say all great literature about big events is written later, with distance. That’s not necessary. Klaus Mann wrote Mephisto in 1936, before the war.

– In that context, is your documentary Extremist, about Sasha Skochilenko (nominated for a student BAFTA), a film about an artist, or a political statement?

– For me that boundary is gone. You just do what you feel. But here’s what matters: in Riga, we shot the courtroom scene with Sasha, and we invited people who had also emigrated and were living in Riga — they played the audience, extras. And when we turned the camera on them, both I and cinematographer Misha Krichman and designer Vlad Ogai — we all understood why we were doing it. These extras didn’t need anything explained, they knew exactly what it was about. Their eyes said it all. So where does politics end, and life, and art begin?

– You left for the U.S. to study after the war began?

– Yes, yes, yes, in August. I had just finished shooting the series The Monastery. But I had already applied to Columbia University back in November 2021, which was a wonderful coincidence. I’d always felt I needed to learn filmmaking. Theater was easier, because since I was eleven I had been working in a good theater, and I sort of felt my way in it. But in film, even though I directed two movies, I always felt like I was leaning on the professionals I hired.

– Do you feel kinship with Treplev?

– No, not at all. That’s a different story, of golden youth. I’m not the son of rich parents. But I was lucky enough to stage a production at the country’s main theater at age 22, whereas Treplev at 22 couldn’t even manage at his own dacha. Of course, Treplev’s sense of life’s tragedy resonates with today’s constant sense of pressure. We don’t know what tomorrow will bring.

– The planning horizon has shrunk, right?

– What does the planning horizon have to do with it?

– That we don’t know what tomorrow holds, and it doesn’t inspire confidence.

– Maybe they’d even like a shorter horizon. They’re in a crisis of purpose: why wake up every day, what’s the point? Those are wasted lives. The characters of The Cherry Orchard aren’t about planning horizons either. Chekhov exists outside the reality of any one country, even outside professions. Sure, he always has a doctor, but outside careerism. Even Lopakhin! Say he gets the estate he dreams of, then comes the railway, progress — but what exactly are his prospects? What’s his business horizon? We don’t know. I think Chekhov’s characters’ problem isn’t horizons, but not knowing how to live. On the contrary, Uncle Vanya says how unbearably long life is.

– Did you see Andrew Scott’s Vanya?

– Yes, I really liked it. I loved how he shifts from one character to another, not by caricature, not by exaggeration, but by moving essence to essence.

– Are there London actors you’d like to work with?

– Of course, there are wonderful actors here. We held auditions for one role in The Seagull, and I realized we couldn’t invite, say, Indira Varma. But then a marvelous actress came in, not so well-known, but unbelievably good.

I’ve actually lost the desire to work with stars. In Myths, I worked only with stars, and the film turned out well. I still think that Bezrukov gave his best performance in Myths — bold, vivid, memorable. But the excitement of “just working with a star” is gone. What’s interesting is offering an actor something they’ve never done before. That’s very hard. What could you offer Ralph Fiennes that he hasn’t played yet? But if there’s a new angle with an actor, then it’s really exciting.

– Is there a difference in acting schools — New York, London, Moscow, St. Petersburg?

– No, I think there are just good actors and bad ones. It doesn’t depend on city or country. Professionally, it all comes from the same roots. That’s why it’s possible to survive and work. When we first read The Seagull in New York, it became clear that we all use the same tools. That was incredible joy — the best day in recent years. I realized my English was enough to explain what I wanted and to get it from the actors. And they were excited to dive in.

But there is an organizational pattern tied to unions, and that’s a big difference.

– Where is it easier and more pleasant to work?

– In Russia in 2014, at the Moscow Art Theatre. One hundred percent. No question. Thanks to Tabakov, we learned to love theater as I think it should be. I worked there for eight years in the space he created — people rehearsed everywhere, morning till night. There was no unprofessionalism, originality was valued, the director’s vision, personal style.

Of course, it’s possible elsewhere — in New York we had wonderful rehearsals. But they ended strictly on schedule! And that’s not the only restriction from unions. The saddest part is how it seeps into actors’ minds. They believe you need an intimacy coordinator, that you can’t touch each other, that you can’t apply too much psychological pressure, that comfort must come before creativity. Hard to get used to, though it depends on who you surround yourself with.

– For example?

– In the States, the stage manager is crucial. After the premiere, you can’t speak directly to actors. You have to write notes, pass them to the stage manager — usually a woman — and she delivers them. I just don’t get that. There’s no cult of the director. Not that I expect my portraits on the wall, but they didn’t even give me a microphone when rehearsing on stage! I’d done the work in the rehearsal hall, had a draft, but on stage it became the stage manager’s job to transfer it. Fine, then let me do her work — scheduling — if we’re swapping jobs! Why is the stage manager allowed to run rehearsals?

But if you find the right stage manager, everything works out. Honestly, if an American director came to Russia, they’d have their own frustrations with our chaos in the workshops.

– And how do workshops operate here?

– I don’t know, we didn’t have them. Try finding a budget for a production with full workshops — not just a commercial show with three stars, but a real artistic statement. But they say the workshops here do run like clockwork.

And by the way, despite all this, in Tel Aviv, New York, and I hope in London, I’ve managed to create an atmosphere of joy in rehearsals, very much like what I once felt in my past life. I’m grateful to everyone who joined me on this journey.

But to answer “Where is better?” — I don’t think there’s any point in speaking about Russia today. Of course, some directors are still working. But how can you talk about theater when Zhenya Berkovich is in prison? I couldn’t possibly go to rehearsals. Maybe I could when Kirill [Serebrennikov] was jailed — he was our guru. But when it’s a woman you applied with to school? Why can you stage plays, and she can’t?

The news I hear is so depressing. Take Ryzakov at the Theatre of Nations — he was promised everything, but two weeks before the premiere his name was removed, and the play came out with no director credited.

And doing what we did before would be impossible now. Maybe because of the simplicity of my artistic talent. My first play, 19.14, was about WWI, about how France and Germany, friendly and culturally intertwined, began killing each other — in 2014, the first Russia-Ukraine war had begun. My second, Rebels, was about revolutionaries across generations. My third, Bright Path. 19.17, about Lenin’s arrival. The fourth, Bulba. Feast, turned out to be about the very war that later began — almost prophetic. When Rogozin in Ukraine read aloud the speech of Taras Bulba, which closes our play, I was stunned.

And finally, Platonov Hurts — about people happily gathering, saying, “What a wonderful evening, pity it’s the last” — and it premiered on February 18, 2022.

The play Crime and Punishment at Gesher Theatre was about deciding who has the right to live. And our current Seagull— it’s about everything that’s happened over the last three years. A very funny, cabaret-style show, with great actors. Truly hilarious.

– If you auditioned in London, does that mean some actors come from New York, and some you found here?

– Everyone except one actress comes from New York. Andrei Burkovsky is also coming from New York. We’re holding a masterclass with him in London. And I hope this won’t be my last project here. We’re doing it precisely because we want to make more.

– Do you already have plans?

– We’re thinking! And we’ll definitely invite people from the theater community to our show. We’ll make noise about our presence. In New York we managed it — we didn’t have a single unsold ticket. May it be the same here.