Anya Ostrovskaya: “I’ve always had a tense relationship with authoritarianism”

Anya Ostrovskaya is a graduate of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. She has several performances to her credit, recognized both by critics and with awards. At the Camden Fringe festival, Anya and her team will present a new work, The World of Yesterday, an adaptation of the novel of the same name by Stefan Zweig. Nastya Tomskaya talked with Anya about the choice of literary material, the theatre today, the tragic fate of Zweig, and hope.

Why are you staging Zweig today? What led to the choice of this particular work?

I read The World of Yesterday a couple of months before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and it felt like I was reading about myself. Zweig experiences the horrifying realisation that the country where he grew up, the language he spoke, read, and loved, suddenly becomes an instrument of hatred. During World War I, this language was already used as part of a military, murderous ideology. And for him, a pacifist and humanist, it was monstrous. It also seemed to me that this was not only about me but about the whole world and all people—how we read the news, how we communicate with others. It’s as if we haven’t moved far from the feeling Zweig described: progress is happening, so many things have been invented, Europe was at its peak, and there were so many humanistic ideas! What wars, what are you talking about! And then World War I begins…

And then October 7th happened, the Hamas attack and the outbreak, the epidemic of antisemitism around the world, which Zweig also wrote about. He writes about Theodor Herzl, about his ideas, about his fate. And I feel that as an artist, as someone who engages in art, I can show my personal reaction through the play. Last year, I staged a play called Theater of the Gulag, which I planned to do with the “International Memorial” before it was declared a foreign agent.

Zweig also describes the world of very young people…

And these people—young, progressive intellectuals—suddenly decided that they needed to annex and occupy foreign land. And suddenly they began to say that if you don’t know how to hate, you don’t know how to love. So I didn’t ask myself why I’m staging Zweig in 2024, but rather how could I not stage Zweig in 2024!

At the same time, Zweig is a very kind writer, and he is very close to people who embrace humanistic ideas.

Yes, he loves people much more than, for example, I do. He has much more patience and desire to understand them. The play grew out of this. By the way, I have three Zweigs. Three different actors play him at three different periods of his life. Each of them tries to find answers to the main question: when would the world still have been saved? When could World War I have been stopped, the rise of fascism prevented?

The genre of the play is cabaret, but the theme is serious, tragic…

Our idea is this: we are in a cabaret space, which takes place in Zweig’s mind. It’s an imaginary world where the actors play different characters: there’s an act with Theodor Herzl, there’s even a soldier performing a striptease. These images emerge from Zweig’s text; I wrote the adaptation myself. The text is very literary, very complex, with long sentences. And as we tell the story, we come up with many different artistic devices. Unfortunately, there’s very little time for rehearsals, so we’ll probably only understand how it all works at the premiere.

Are you creating the play specifically for the Camden Fringe festival?

If you don’t have a budget, festivals like this are essentially your only access to theatre, to an audience. You don’t pay for the venue, you just pay a deposit, which you get back if you sell tickets. I want to show the play, I want to get paid for it, I want to pay people their salaries. And also—take the play to Europe. Because it’s not really an English play…

What do you mean by not really an English play? What should a play have to be called English?

For me, British theatre is when the actor on stage works directly with the text. It’s not the director’s theatre. Either you have Andrew Scott playing Uncle Vanya…

…or Present Laughter with the same Scott, which is an entirely actor-driven play?

Yes. Either you have a playwright, or you have an actor. Now, let me ask you to name directors you’d like to work with! I’ve spent six years here, and I can’t say I’ve found one.

And so yes, we work at Fringe because you either have a huge budget, or you do something with three actors and no set design. This is a problem for me in English theatre: I don’t feel that with my limited resources, I can do ambitious things. Take, for example, the fact that few people know Zweig well.

It’s worth mentioning that a play based on Zweig was very successful at the Salzburg Festival.

That’s why I would like to bring the play to Europe—to Germany, to Austria. We invited the Austrian Cultural Center to our performance. Let’s see if they like that I have two women playing two of the Zweigs. I don’t know what their reaction will be. In short, on one hand, I feel that this is a very relevant story, and on the other, I’m working somewhat into the void. I have absolutely no idea who my audience is.

How do you envision your ideal audience?

It’s someone who wants to be surprised. Who wants to feel. Someone who has some cultural context. It’s probably selfish to say, but I want my audience to be interested in what I do. It’s very difficult to tell a story when the audience doesn’t even know who Zweig is. There were reviews of Theater of the Gulag, which was staged as a promenade, saying that it wasn’t immersive enough. I thought—well, what next, I don’t know, will they execute you at the show, would that be immersive enough?

And at Fringe, you get a very different, very varied audience. There are people who really go to the theatre, and there are people who just come to relax and have a beer. And here I am—sorry, but I’ve got Zweig.

A real theatrical indie project… Who is working on it with you?

I had an open casting, and as a result, we formed an international team. There are actors from Poland, England, Israel, Ukraine. Almost all are immigrants, just like Zweig himself.

When did you realise that theatre was your calling? And why didn’t you study at a theatre school in Moscow, but moved to London?

I was born into a family of directors and screenwriters, so being involved in art was natural for me. I studied at a theatre school affiliated with the Shchepkin School, but Shchepka didn’t really consider us part of them. To be honest, I wanted to leave Russia quite early. I collaborated with the Gulag Museum, made documentaries for them, interviews, and this work made me think. And besides, I love English culture very much; I wanted to study in England. And during my studies here, I realised that I had freedom, real freedom, and I could do what I was interested in. I’ve always had a tense relationship with authoritarianism, just like Zweig.

Does Zweig come to the same tragic end in your play that we know? Would you want to save this person from deadly despair and his final act?

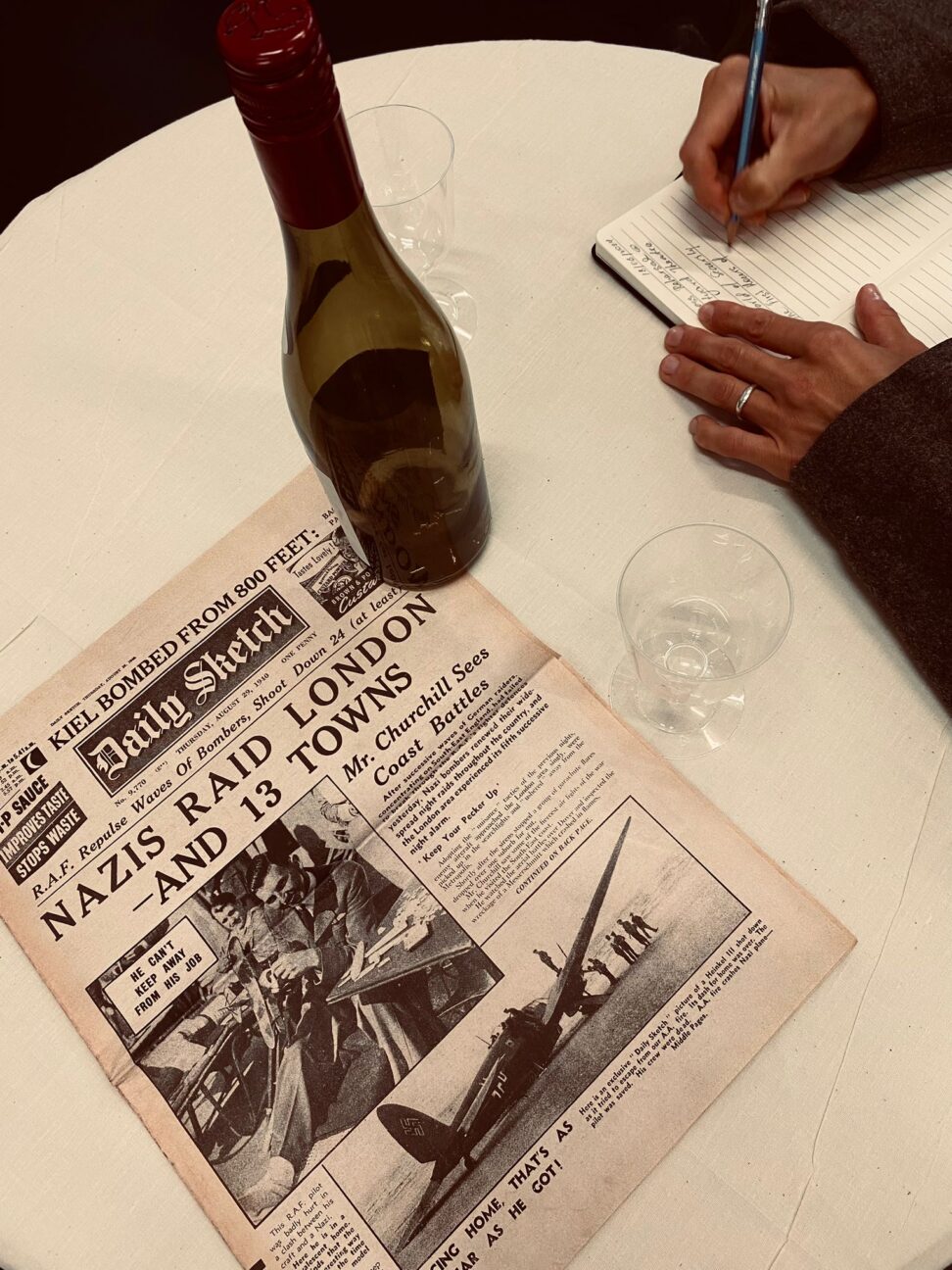

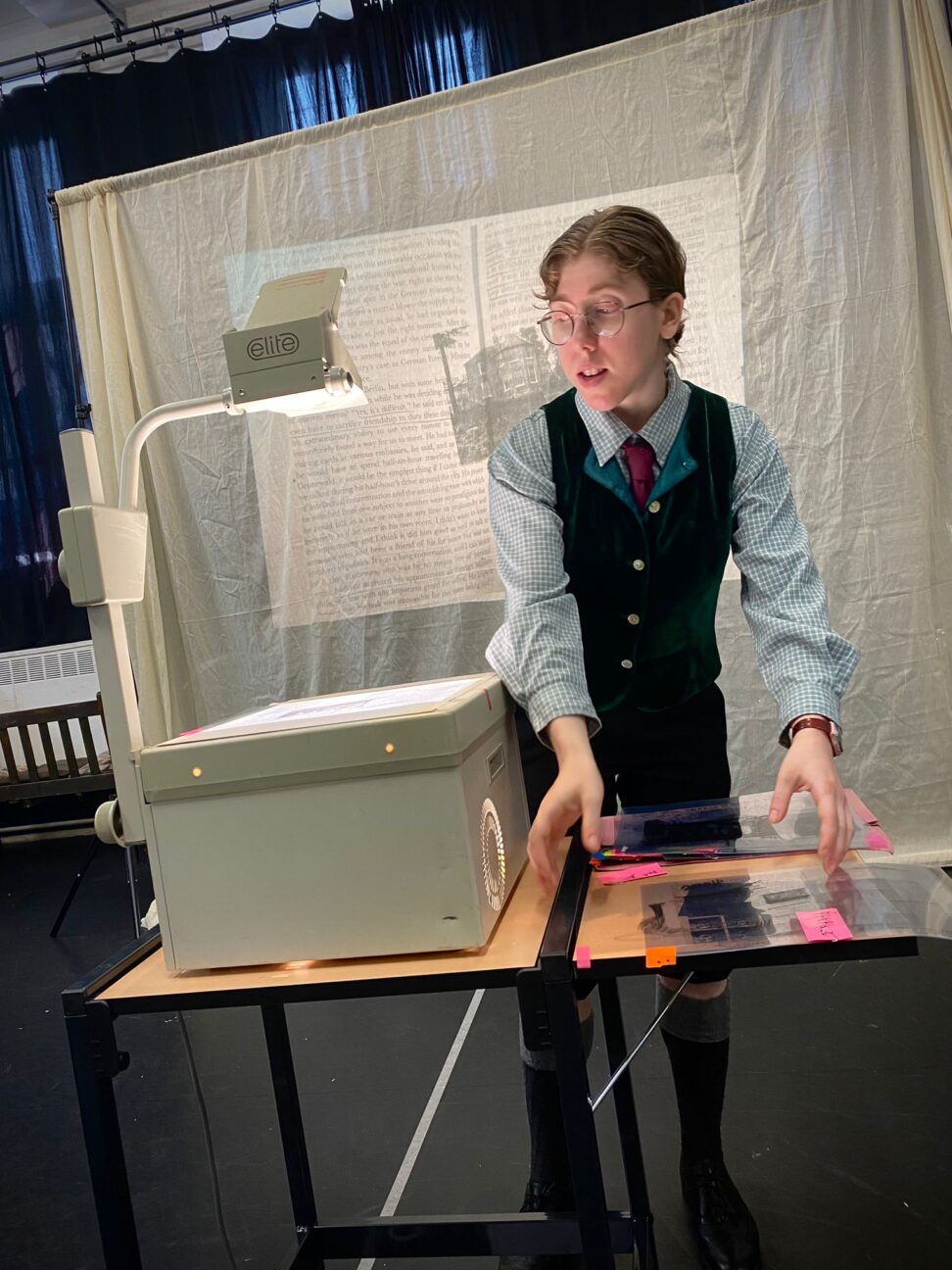

We were just talking about this at rehearsal today. I think it’s important to show a person who witnessed wars, the workings of propaganda, the rise of antisemitism. My play is about the fragility of the human world, about how easy it is to destroy it. An old projector shows slides—archival photographs, documents, newspaper headlines from that time. And the headlines from World War II transition into today’s headlines. And not just about Ukraine or Israel—about everyone. And we bring our Zweig into the present day. He asks the same question—could something have been done? For Zweig, who committed suicide, the answer is obvious—no. It seems to me that only those who don’t watch the news now don’t feel the same. But I believe there is hope for salvation. For example, because we, an international team in London, are staging Zweig today.