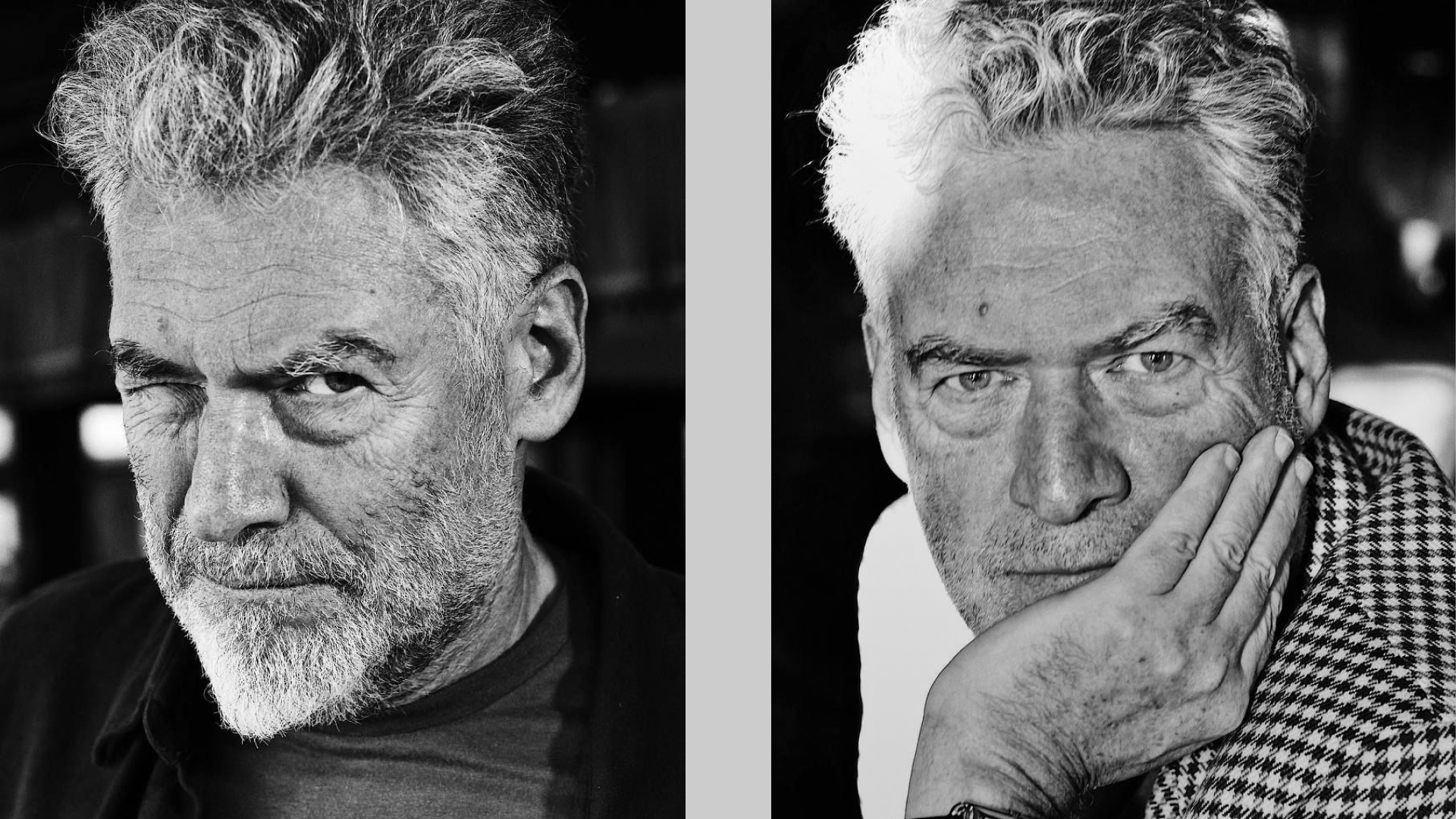

Artemy Troitsky: “My goal is to make sure people have fun and comfortable dancing”

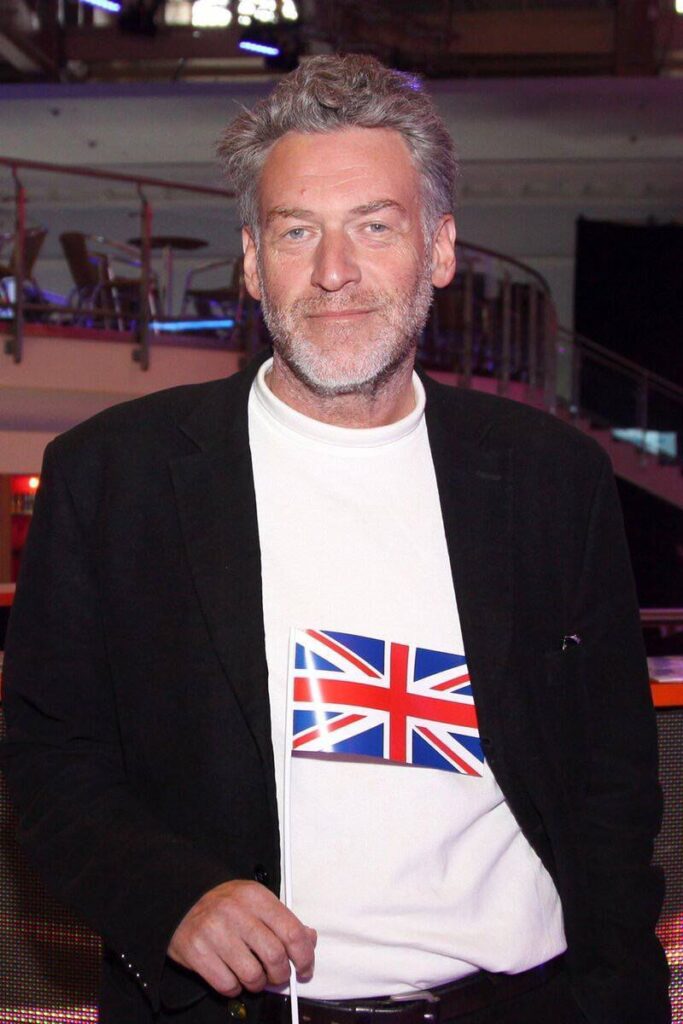

In November, Artemy Troitsky — historian, music critic, host, and writer — will give a series of lectures on Russian rock in Oxford and Edinburgh. In London, however, he’ll be doing something quite different: hosting a full-fledged disco — after all, Troitsky began running the very first discos at the main building of Moscow State University when he was still a young man. His visit to the United Kingdom is organized by UK Integration and Masha Macmin, a cultural producer who has spent several years developing humanitarian and educational projects between the UK and Eastern Europe.

Of course, Troitsky needs no introduction for Russian-speaking audiences. He wrote some of the very first Soviet articles about The Beatles and Deep Purple while still a schoolboy, at a time when rock music was banned in the USSR. Since then, he has done it all — journalist, producer, editor, lecturer, interviewer, even musician and DJ. Sharp, uncompromising, a true self-made man. Who doesn’t remember Café Oblomov or FM Dostoevsky?

We spoke with the historian — and in a way, creator — of Russian rock about film, music, and Soviet hits.

In the 1985 Dire Straits song “Money for Nothing,” Sting sang, “I want my MTV.” And now, in 2025, MTV has disappeared from the UK and other countries. How do you feel about that?

From a purely nostalgic point of view, it’s a little sad, a bit sentimental. I once worked part-time for MTV Europe, which was based in London near Camden Market. I remember one funny episode — I was introducing actress Natalya Negodaon MTV, the star of the sensational Soviet erotic drama Little Vera. We talked about sex in the Soviet Union and other spicy topics.

But returning to our not-so-cheerful times, I think MTV’s departure — though partial, not total — is completely understandable and commercially justified. MTV and other music TV channels have lost both their audience and their appeal. So naturally, with their influence declining, they’ve had to cut staff and close branches.

The days when music channels drew viewers by showing trendy music videos are long gone. Music videos simply aren’t the cultural phenomenon they were in the 1980s and early 1990s, when famous actors starred in them, and top film directors shot them, and fans eagerly awaited premieres. In Russia in the 1990s, we even coined the fashionable word “clipmaker.” All of that is in the distant past. Now people discover new music online, primarily through YouTube.

I work with teenagers, and I saw how they were recently counting the days until Taylor Swift’s new video premiere.

That’s more about Taylor Swift herself than about the medium of the music video. She’s managed to captivate young audiences worldwide — quite mysteriously, I think, since, in my opinion, she’s a rather ordinary singer. But yes, people eagerly await her albums, songs, and videos. There’s no denying that Taylor Swift is the biggest star of her generation. In terms of sheer fame, she stands alongside Paul McCartney, Bruce Springsteen, and Bob Dylan. Whether she truly deserves that status is debatable — but it’s a fact.

What’s the secret of stardom? Can someone be “constructed” into a star?

Unfortunately, yes. Some people become stars for fair reasons — they’re talented, gifted songwriters, composers, and performers. Think of The Beatles, or Sting, or Mark Knopfler, who wrote “Money for Nothing.” Wonderful musicians, great vocalists. In Britain, you could name PJ Harvey or Beth Gibbons of Portishead.

When a talented, charismatic person becomes a star, that’s natural. Of course, there’s always support — good producers, wealthy record labels, and clever PR campaigns. That’s fine.

What’s less fine is that very often stars are made out of people with no special talent at all — just a pleasant, sexy appearance, good choreography, and lots of coaching. But empty inside. That too happens all the time — that’s show business. There are plenty of skilled professionals who can turn a mediocre performer into a superstar. You can’t really escape that reality.

On the Russian-language scene, we’ve seen a bright new star — Liza Monetochka, whom you’ve even included in your London disco lineup…

Monetochka has been living happily in Vilnius, Lithuania for several years now, and she tours successfully around the world. She’s a very talented young woman — I’ve seen it myself. A great songwriter, great studio artist, and a truly captivating stage performer. She writes wonderful songs — no wonder some of them have become anthems that everyone sings. Her last big hit, “It Happened in Russia, So It Happened Long Ago,” is a fantastic song.

I think she’s the most talented Russian-language artist of her generation. You can draw a line from Alla Pugacheva, to Zemfira Ramazanova, and then to Liza Gyrdymova — Monetochka.

You mentioned Springsteen and Dylan, and that brings me to my next question. Biopics about musicians are everywhere — Dylan played by Timothée Chalamet, Springsteen by Jeremy Allen White. Why this surge of interest?

I think the main reason is simple: these are artists who wrote and performed outstanding music. Their songs are still loved, still sung in karaoke, and people remain fascinated by their personalities.

Most of them also lived dramatic, interesting lives. That’s what drew filmmakers to the first musician biopics — “Lady Sings the Blues” about Billie Holiday, “The Doors” about Jim Morrison, and “Walk the Line” about Johnny Cash.Tragic figures, many of whom died young.

Today, we’re getting more biopics not just about tragedy, but about famous musicians in general — because audiences crave these stories.

In Bob Dylan’s case, for example, his life wasn’t especially tragic. Most of his inner dramas ended in the period shown in “Complete Unknown” with Chalamet — his early years, the affair with Joan Baez, and the struggle between folk and rock. After that, he settled into his role as a great poet and musician. I doubt you could make a very dramatic film about Dylan’s last 50 years.

Biopics will keep coming. I’m sure we’ll eventually see ones about Prince, Janis Joplin, and John Lennon — if Yoko allows it. I really don’t understand why there still isn’t a proper film about Amy Winehouse — now that was a real tragedy.

Young people watch these biopics, even though for them this is “daddy’s rock,” as the English say. Back when you ran your discos at MSU, did you see them as educational projects?

I started running a disco with friends at Moscow State University on the Lenin Hills in 1972, and it lasted for two years — the very first disco in Moscow, maybe in all of Russia. We did it simply because we adored music — especially Western, Anglo-American music, which we were crazy about. And we weren’t alone: all the forward-thinking youth in the country loved it, especially since it was forbidden fruit.

You almost never heard that music on the radio or TV, and no foreign artists toured the USSR. The Rolling Stones wanted to come from Warsaw to Moscow in 1967, but the authorities stopped that “cultural sabotage.”

Our disco went like this: in the first part, I’d talk about my favorite bands and play vinyl albums. Back then I loved progressive rock — Pink Floyd, King Crimson, Jethro Tull, Frank Zappa. Then for the next two or three hours, we’d just have dancing, playing lighter music — glam rock, David Bowie, Marc Bolan, regular rock’n’roll and rhythm-and-blues. People loved it. The university’s Komsomol officials, however, didn’t — and after two years, they shut us down. These days, I DJ only occasionally, but I still enjoy it.

You’re bringing your disco to London, but it will feature Russian-language music — from Magomaev to Monetochka?

Yes, it’s the opposite of what I did in the 1970s. Back then I played Western music in Russia; now I’ll play Russian — or Russian-language — music in England. It’ll be a real disco, though I call it a “humanitarian disco.” That’s my own invention.

I used to do these in Moscow at private events. It’s not a scientific or educational project like my old progressive-rock sessions — it’s a proper dance party, with brief comments and little stories behind the songs.

My goal is to make sure people have fun and comfortable dancing. That’s not exactly a strong suit of Russian pop and rock — compared to international club hits, ours lag behind. But in the 60s, 70s, and even today, there are songs you can happily dance to.

For example, the great Muslim Magomaev will delight us with his twist-rhythm song “The Best City on Earth.” And from Edita Piekha, we’ll hear “A Wonderful Neighbor Moved Into Our House” — a cheerful, melodic dance tune.

I’m not catering to primitive tastes — only cool, clever, and talented songs, even if a bit nostalgic. I love this music myself, and when I’m at the DJ booth, I can’t help dancing along. I hope even the local churchgoers will like it too.

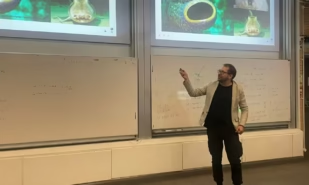

I was struck by your idea comparing the Decembrists to rock stars — you’ll be lecturing about this in Oxford and Edinburgh?

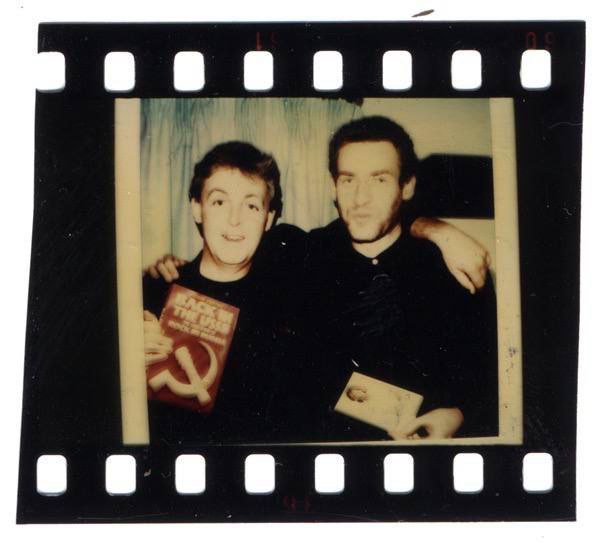

Yes, that’ll be an experiment. I’ve had three books published in the UK. The first and most famous is “Back in the USSR: The True Story of Rock in Russia” (1987). My third book, “Subculture: The History of Russian Youth Resistance 1815–2018,” came out in 2017. As the title suggests, it traces youth movements — mainly protest ones — in pre-revolutionary, Soviet, and post-Soviet Russia. It starts with the Decembrists and ends in our turbulent present.

I gave a course on this topic at King’s College London in 2015, which led to the book’s publication. So now I’ve decided to combine my first and last books in one lecture — starting with rebellious Russian youth, from dandies and Decembrists, and moving into the 1960s and 70s, when protest and subculture took musical form through the stilyagi and hippies. This time, though, no dancing — but I promise it won’t be boring.