Between Colour and Silence: The Art of Sophie Lévy Burton

After seeing The River Beneath the River exhibition and being deeply moved by its quiet intensity and emotional depth we felt compelled to talk with Sophie Lévy Burton about the inner world that inspires her paintings. The artist considers intuition, metamorphosis, and the enigmatic relationship between art and soul in this discussion of the spiritual and psychological undercurrents that direct her work. What emerges is a profoundly intimate investigation of creativity as a means of self-discovery, healing, and reconnection.

Your debut solo exhibition is titled The River Beneath The River. What is the symbolic significance of this title, and how does this idea of a deep, underlying current manifest in your new body of work?

It’s an old, old Spanish phrase, Rio Abajo Rio, and I first came across this phrase when reading Clarissa Pinkola Este’s Women Who Run With the Wolves. I remember being startled when I read it, I found myself in its pages – especially this compelling idea that there are two women, an outer woman and an inner woman. The phrase The River Beneath The River refers to the hidden force that lives beneath the surface in a woman. It refers to her deep life – which often funds her mundane life. It basically refers to her hidden or crushed true Spirit or Soul.

It was a very powerful idea to me, resonating immediately. You know painting has been a calling to me and I feel somehow this mysterious process has reclaimed my true self, my soul, lost in the wilderness of life. So you could say that the river beneath the river is a language for my soul.

In that book Pinkola Estes paints a vivid portrait of women reclaiming their true nature often through wild creative acts… But this is exactly how I feel about abstraction. In the intentional solitude of my studio and through an almost altered state of consciousness whilst painting… I have somehow retrieved my true self.

You know when I first started painting, I would sit down and say what is my soul wishing through me? That was part of the calling. The river has risen up and flowed me (literally a flow state) to wholeness. Reclaimed my dead parts. Brought me back to life. And you’re asking what the title means symbolically but in actual fact it’s almost literal! The process and the impact of the colours returned me to life.

What feelings do you hope viewers will walk away with from this exhibition?

When I paint, I do it for myself and not an audience, and yet a painting I believe is simply never finished until it has a reception, a response, or an audience… then the painting’s “heart” can be held. This is the mystery of a painting and a work of art. It is a conversation only half had without an audience.

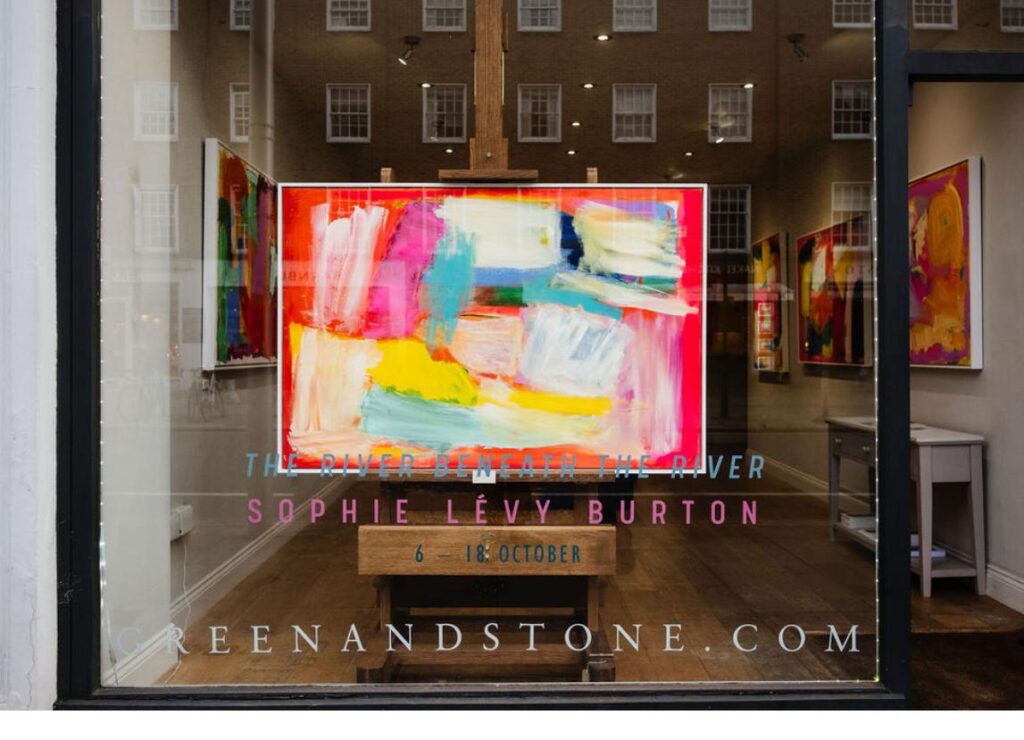

So there is a very deep meeting spot for the artist and the viewer and the painting becomes that ground of meeting. And if you like, it is a spiritual handshake. So there is a certain ecstasy and emotionality to my colour forms which I hope will provoke a spiritual response, uplift and joy. I would hope that the colour and the colour forms meet the viewer at a very deep level because this is from where they have sprung. Actually when Hester Baldwin (the wonderful gallerist at Green and Stone) came for a studio visit to Hove, she walked in and pretty much fell into tears as an immediate emotional response to the paintings. It was a very gratifying response for me.

You speak of being led by your “painting animal,” trusting the colour to guide you. How do you maintain this connection to pure intuition and “childlike” freedom while simultaneously exercising the discernment needed to know when an abstract work is finally complete?

There is no intellectual or academic discernment in any of my paintings… They have come from somewhere else, conjured from somewhere else, somewhere deep in the cosmos of my own body. You must understand that this process is all still mysterious to me! It still has that spontaneous revelation quality “glittering” around it. I am painting like a child. In fact, I feel like a child when I paint. And like a child, I am living in the moment, even the moment of the moment. And I hope that never fades to be replaced by… intellect, self-judgement, self-criticism. I have had enough of that in my career as a writer and journalist.

I spend a lot of time looking but when I look it is my soul looking, my spirit. It is not my mind. How do I know when they’re finished? There’s always a visual harmony that is reached and then a settling, a gentle settling about the painting, a gathering of time, a pause… then… done. The conversation is over. The conversation I have had with my soul – the forgiveness, the memories, that revitalised spark – is done.

And although you have not asked me, I have to tell you that when I stand back weeks later and look at my paintings I simply cannot remember having painted them. It’s a very interesting thing.

This for me has been the revelation of abstract form – the paintings manifest around feeling, intuition. This is why I’ve ended up calling them a soul language because I can’t think what else to call them.

Your journey involves inner work, including a shamanic circle. How directly does this non-visual, meditative practice of trance, drum work, and inner journeying translate onto the canvas? Is the language of abstraction, for you, inherently spiritual?

I would say from my own experience with shamanic practice there is a direct engagement with the unconscious in the same way that there is a direct touching of the inner world whilst painting. Maybe as an artist I enter a similar world as when I am being carried on the beat of a drum. Both are altered states. And maybe the imagination is an altered state anyway…

It’s interesting how this might translate onto the canvas, but I would say that every experience with drum work and shamanic journeying weaves you to a finer point, a finer spiritual point, because it is all spiritual work. Who you truly are, what you’ve blocked from Self. So when I come to paint, my entire Being is sharper. I have grown in that period, so I suppose you could say it is almost like gym work before a marathon or a run. I regard my work in the shamanic circle has certainly made me fitter as a painter.

For myself I feel I go deep into an inner world where there are archetypes and symbols. It’s similar to the world of sleep and dreaming. It’s like gifts are offered to you in this runaround every day life that we lead we can forget, and perhaps we need to forget in order to get stuff done.

As to whether the language of abstraction is inherently spiritual… It is non-verbal. You know the Universe, the cosmos, it’s all so deeply mysterious still. In abstraction, you have shapes, marks, and forms that absolutely move people spiritually, blocks of colour, colour punching at you, all this effecting the eye and provoking the soul. I mean look at Rothko, de Kooning, Pollock, all the greats. People make pilgrimages to their paintings. It’s one reason so many people love abstraction as opposed to an image of a vase or a field. So it is certainly some form of soul language – or souls wouldn’t respond.

As the Editor-in-Chief of MONK, a magazine that curates discussions on creativity and consciousness, do you ever find yourself struggling with the duality of your role—applying the same critical, editorial lens to your own vulnerable paintings?

No, amazingly I have been able to siphon off that persona and split off my editorial self. And I’m glad because it’s a necessity you know, because I couldn’t paint like this if I didn’t. The critical mind would stop the flow. The intellect would get in the way. It would argue and bring reference in. In fact when I realised that painting was a calling, I suspended MONK entirely. I needed to allow myself a complete dwelling in this wholly different and consuming creative process.

Part of me will always be a writer and will always want to write. After I’ve been painting seriously for a few months and I realised what a transformative journey this was, I began to keep a diary. My writing style in this diary is not like anything I’ve written before; it’s quite abstract, similar to my paintings. Fragments of words, of sentences, much more immediate. I am now taking time to shape this diary into a spiritual memoir but from my own experience of working in two creative mediums I would say they don’t run together. They run in separate and parallel worlds and use different aspects of my psyche.

Can you describe a moment from creating this exhibition where a memory or an emotional state you hadn’t realised was present suddenly surfaced and guided the direction of a canvas?

Most of the paintings are painted around or created within a memory or a faint whisper of a memory. I would say this is all very deeply unconscious. When I begin a painting, I begin with a colour or a combination of colours and then the conversation with my inner being starts, and memories may well roll or flow, but you understand it’s like a faint mist or a whisper. There is something very beautiful and healing about the practice (especially as I did not seek it, but it sought me…)

I’m very happy to be intimate in this interview, so I can tell you that I was abused as a child. Now when I paint those memories have come back – bad stuff that I’ve forgotten or blocked… but almost miraculously the paint transforms them – the process and the practice of abstraction transforms them alchemically and returns me to the joy that I felt in very early childhood, because I was a very joyful child – before I was preyed on.

And we must remember that this joy is our natural birthright.

And good memories roll in as well. Two memories in particular, I am happy to share them, and they’re very relevant to my painting.

I am about four years old during Spring. I am in the garden, looking up at an almond blossom tree which is thick with pink blossoms. I had forgotten this memory but painting returned it to me. Not only that, it returned the feeling. Because in that moment – a child under the pink blossom – I connected to something deeply beyond me and also within me. Feelings of expansion, connection, and love. I was a child having a deeply spiritual experience. That memory I believe is present in a lot of my paintings.

I feel emotional just talking about it now.

The other memory – I am five or six, and I am running with a little apple pip to plant the pip in the wilds around my house because I know God will grow the apple pip into a tree. It sounds like a fairytale! Again, I had forgotten this joyful, confident, trusting moment in the Universe. Somehow my painting process reclaimed it for me. I remember returning for days, wondering why there was no apple tree! I laugh now at the wilfulness, the innocence and the trust of my child Self. I thought the pip would grow quickly magically into a tree because that’s what God does with apple pips. You’ve asked me for specific memories but these two memories resurface and circulate in my studio. They are a strength, an energy. They connect me to a sense of my true self, my pure self, my soul self – before the shadows came and stole them away. I believe this is the whole point of my work. And I believe this is probably what Carl Jung meant when he talked about the golden child or the inner child.

So my painting never connects me to the bad “stuff” memories because the bad stuff is alchemically transforming in the process. These feeling-memories are treasures and I hope the treasure is shining in the canvas.

Can you walk us through the sensory experience of painting in your studio? Does the weight and materiality of the paint itself—the mess and the motion—act as a necessary counterpoint to the spiritual lightness you seek to achieve?

Yes, I can be very athletic when I paint, and I often dance which is very common for a lot of painters. Music frees the spirit and opens the body, the cells and organs, everything responding. I can cry and laugh. It is as if the canvas becomes my partner.

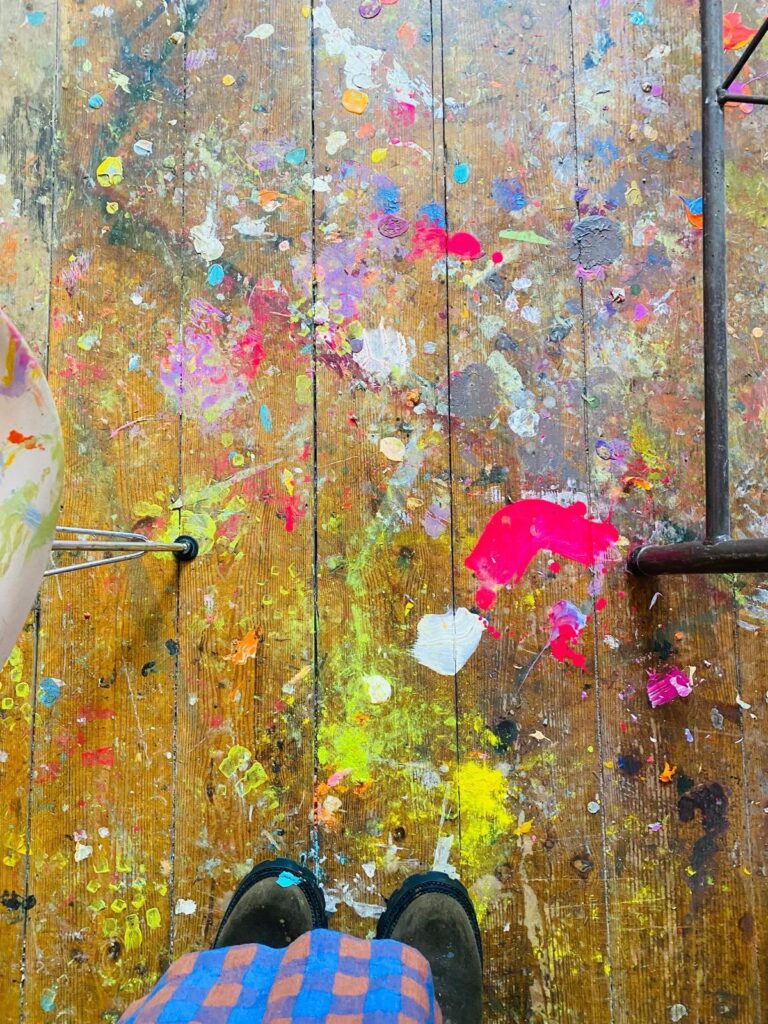

In my studio, I will start with a colour and then my painting animal arrives and the conversation really starts. Sometimes the rhythm is fast, spontaneous. I use my fingers to paint and often use my left hand which is supposed to be more intuitive as I am right-handed. I will grab materials from anywhere in the studio to push paint around, or just the pallet knife and brush. I’ll paint straight onto the canvas, straight from the tube or the pot. A lot of my painting friends think this is very unconsidered, and yet, I don’t think I could paint any other way. I am untaught. I never want to be tamed.

Most people exclaim “Oh my God!” when they walk into my studio – not because of the paintings, but because it is frankly a beautiful colour-bomb mess. The wooden floorboards have become real works of art. And isn’t that what life should be? Colour-filled. Who wants to live their life in black-and-white?

Given your focus on finding wholeness and light, what are the non-artistic daily rituals or habits in your life that you rely on to sustain the creative energy required for your demanding, large-scale work?

I have a deep expression of love of God and the foundation of my day is always a simple ritual of chanting, prayers and meditation. If I don’t do this simple half an hour practice in the morning invariably my day will go comically awry, and I certainly won’t paint as well.

I use a singing bowl with a low tone that I bought at Samye Ling Tibetan monastery in the Scottish Borders. I will chant the Bija mantras (the vibration fine-tunes the chakras) and on my mala beads, the mantra Om Mani Padme Hum. Hail to the jewel in the lotus! Glorious, mysterious chant.

I am neither Buddhist nor Christian. I am an absolute spiritual mongrel, a little bit pagan even. I always say the Our Father – it is the prayer I was raised with and so what God gave me in this life as “my start” (although I often change the wording to Our Mother or Our Love or Our Light).

These practices keep me present in those minutes and somehow miraculously that will extend through the day. I will also try to stand with bare feet on the grass and do some simple yoga outside.

This might all sound a bit bonkers, but it’s the way my spiritual practice has evolved. Even if I don’t feel like doing this, this strange collage of worship, I force myself. It’s about spiritual health. And if I don’t do it, as I say, the day’s alignment is totally off…

I have let go of trying to follow one path to God and delight in the feeling that all paths lead back to Source, to God and to our true self. When I worship formally, I can go to the Quakers, the Catholics or the Buddhists. The main thing is to stay awake – we must stay awake spiritually. And keep our hearts open. Love is everything.

Explore Sophie Lévy Burton’s art at www.sophielevyburton.co.uk

Comments are closed.

21 Comments.

It is the same feeling The River Beneath the River. You are fortunate that you got colours to express. Your presentation will guide the people who are lost in grays.

Sophie’s work comes from the soul and its hidden memories, and speaks soul to soul, compelling a personal response from the viewer.

What a curious alchemy. The colours glow and flow into a secret unconscious. The imagination of our childhoods rekindled through passages of light.

Powerful stuff. Wish I’d seen the exhibition.

I didn’t see the exhibition either, but the even photographs have a certain power. Lee Krasner used to say that it was a matter of whether the abstract canvas allowed her to breathe, or not, whether the canvas soared into space or felt earthbound. That all good canvas should be alive. Perhaps there is something similar going on here.

These are exceptional photographs and reproduced to a size that does give a real impresssion of the originals’ glow and presence, even down to scumbling and impasto. It’s good you remind us of Lee Krasner’s words – you might have seen ‘Lee’ at Park Theatre last month. Krasner remains one of the most articulate artists about painting, as well as a wonderful painter who would understand Sophie’s work.

Gaining an insight of the process behind Sophie’s painting has been entrancing and I have been captivated by her spiritual journey as an artist but also touched by her candid and beautiful way of talking about her art…

I had seen photos of her paintings but when I attended the private view at the gallery, I was blown away by the vibrancy of the colours of the actual paintings. A sensory overload of happiness oozing from each work, yet each painting appealed to me by connecting me with a different joyful memory which made me reflect as how colours affect you emotionally…Sophie’s alluring art works are the epitome of positive energy in my opinion and I thoroughly enjoyed how she wonderfully expressed herself in this fascinating interview.

Colour speaks louder than words!

Beautiful expression

Like the abstract expressionists, these paintings manage to evoke the sublime! Great interview.

I found Sophie’s recent exhibition vibrantly optimistic and so positive in these gloomy times. I bounced out of it. But felt I was perhaps missing something with the title: ‘The River Beneath The River’. After reading this soulful interview – I feel there is a deep peaceful river of calm running beneath all that jubilation It’s lovely and it’s a lovely interview.

‘Vibrantly optimistic’ is right – ‘d not thoguht of optimism, since Sophie mentions joy, but of coruse it’s optimistic, as the work is about futures and portals as much as it is about the present. It’s a delicately probing interview thoguh I stil think your initial response is equally valid.

Fantastic spiritual journey in the work, fabulous article .

what a promising debut. We’re sure to witness more impressive work

An exceptional interview with an artist rare in her openess about herself, her inspiration, and the spiritual nature of her work. Her art is all about the extraordinary power and mystery of colour , and for her the colour is the meaning. Both paintings, and article, full of interest and beauty.

That’s so precise – for Sophie colour is the meaning: an absolutely gifted colourist who finds form that facilitate the colour rather than subordinate it. THe release of spirit.

What is so striking about this interview is that it at once sheds light on the process of painting these large, bold, vibrant canvases as, to quote Gillian Ayres, ‘arenas in which to act’, the paint itself working in all the materiality of the pre-verbal, AND leaves open our active engagement with the liquid thought and feeling, the brushwork, the impasto, the marks, the texture strokes built up in layers, the energies of the paintings themselves. The paintings resonate (though different paintings for each person) in a way blazoned for me by the frontispiece to Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’: the visionary stepping over the threshold, carrying a light, through the doors of perception.

Beautifully put: the intersection of materaility, the brushstrokes and impasto, and the abstraction of glow and light they give off. Didn’t know the Ayres quote.

An exhilarating read, and there’s much about spiritual practice and how inhabiting a spiritual/psychological space impacts on painting. Only the artist can talk of that interiority: my focus is on the painting. And Sophie Lévy Burton has appeared as a painter in mid-life without any formal or informal training, and with a few pointers, inspirations.

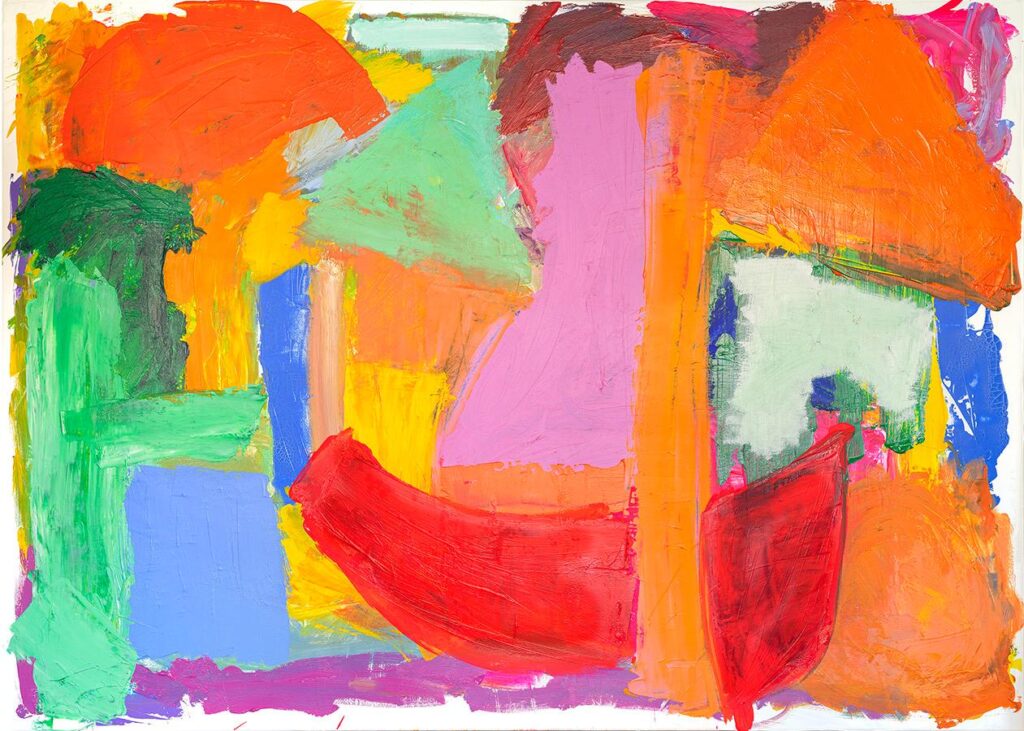

Gillian Ayres might be a starting point but Lévy Burton’s structures as such aren’t these tubal swirls and curious recessions. They’re interlocked forms on the point of dissolving, and planar – on one sensory plane as far as I can see. This isn’t the formal rigour of say Hans Hofmann (whose colours Levy Burton also recalls), since the underlying structures as such are provisional, and literally you can see the blocks of colour call to each other and vibrate. There’s joy here: sometimes it’s fierce and uncompromising. Occasionally it melts. Most of all though this is a kind of painting that refuses nightfall and its mental states; and that’s rare. The River Beneath the River evokes both psychic and physical states (think of London’s underground rivers), and invokes a hidden mineral life discrete and channelled of itself.

I return to the surfaces, those crusty palimpsests and crests of impasto: the excitement of creation. Most of all the size of the photographs lent the imaged paintings a glow that even a gallery can’t always lend. Especially in the bustle. There’s an extraordinary radiance in the colour – and when you consider the impasto effects, this luminousness is nothing short of astonishing. You can see this in the locking and layering. There’s also no muddy joins, no dull opacity. Partly the bright clarities of acrylic help, but can’t explain Lévy Burton’s gift of balancing – sometimes in an unconsidered sweep – colour contrasts. Without being dragged down to muddy paint-death. It’s perilous, this pristine world, but worth the price of risking – without underpinning, without drawing, without sketches, without a masterplan. That’s why it transcends the need for them.

A longer pespective (a far, far shorter one is posted below)

An exhilarating read, and there’s much about spiritual practice and how inhabiting a spiritual/psychological space impacts on painting. Only the artist can talk of that interiority: my focus is on the painting. And Sophie Lévy Burton has appeared as a painter in mid-life without any formal or informal training, and with a few pointers, inspirations.

Gillian Ayres might be a starting point but Lévy Burton’s structures as such aren’t these tubal swirls and curious recessions. They’re interlocked forms on the point of dissolving, and planar – on one sensory plane as far as I can see. This isn’t the formal rigour of say Hans Hofmann (whose colours Levy Burton also recalls), since the underlying structures as such are provisional, and literally you can see the blocks of colour call to each other and vibrate. There’s joy here: sometimes it’s fierce and uncompromising. Occasionally it melts. Most of all though this is a kind of painting that refuses nightfall and its mental states; and that’s rare. The River Beneath the River evokes both psychic and physical states (think of London’s underground rivers), and invokes a hidden mineral life discrete and channelled of itself.

London Cult has published not only a ranging, perceptive Q&A, they’ve generously illustrated it with examples of Lévy Burton’s paintings. Two paintings, ‘The Circus’ a work centring itself in blocks and circles essentially pinks and whites, is grounded n dark surrounds themselves kept at bay so as not t create too easy a perspective. Centring is a favourite Lévy Burton trope: the foundational juxtaposition of orange and yellow, mitigated by a negotiation of lighter shades. Indeed white blocks blaze like noon bars on an intense tropical day go hovering across, like light over the gestural colours of show. ‘The Leap’ enjoys a similar colour scheme again with a white block more central, and a Prussian blue (mixed with Ultramarine) triangle claiming a kinetic relationship it the pink/orange interlocked blocks. Another patch of that blue echoes from above. Beyond to the right, something unusual happens, unique in Lévy Burton’s output: a dimness or dark-grounded magentas, shadowed yellows and a Suffolk pink arch enclosing a deep ultrmarine lancet. Is ‘The Leap’ worth it, literally it seems a leap into the dark, left to right. ‘The Leap’ is an active painting, though should be taken as one of inner light, faith, or imagination.

‘The Monastery’ is unusual for presenting bars of colour as structural and interlocking shapes, not wholly unlike those we might have been presented with as infants. Here though, there canny balance of shapes, colour juxtaposition (the right side is almost exclusively oranges and pinks (in reality light violet echoing a magenta ground diagonally opposite) partially bounded by a glowing bar of cadmium yellow itself backgrounded; and the left third in light emerald and light cobalt blue.

There’s two elements that militate against what might be seen as representational, a series of aisles for instance. One is a sweep of red towards the right near the bottom itself bisected by an orange pillar or bar but intercepting that read as it sweeps up in curve. It’s the one curvilinear form and immediately draws attention to itself in shape and colour. It’s enriched by some blackish scumble that’s subtly done, adding a tonal weight. Lévy Burton uses this rich resource sparingly, so as not to muddy the effect. It’s like a shading on a drawing relying on its line and shadowing only when strictly necessary. The whole of this red wedge, notwithstanding that bisection, is that of a banana-shaped boat; with a distinct boundary especially on the right. And above that end-point a kind of insert mid extreme right punches out like a window: its ground is originally ultramarine, but yellow has skimmed it then a palimpsest of green and lighter green-grey then smirched by a greenish white, a kind of faded light mint. This complex above the deep red fulcrum acts like a kind of window above, a density of nature it seems to counter the human scale of building.

This might veer to a naturalistic projection on an essentially abstract theme. But the painting’s grounded in a name, and identifiers naturally suggest themselves. Just as clearly through, Lévy Burton refuses clear perspectives, and the evocation shimmers in the mind’s eye of someone who was there, perhaps in summer. More importantly, it’s a unusual essay in rectilinear forms slightly swung, as if jazz has broken through some classical lines.

Besides such vibrant paintings ‘Peace Offering’ – quite large too – comes as a point of rest. Grounded in cadmium yellow with pink, orange and red lozenges, it’s interrupted below by a rhomboid of deep mint green shaded by a little yellow to tint an organic under-belly. To the right is a vertical of white that shoots up as n alabaster column then veers right in a widening but still slim tapering: the whole seems like an Art Deco abstraction of a gramophone horn. The work quietly asserts its peace.

To its right is a much smaller, far more busy and interlocked painting: ‘Let’s Go to India’ enacting something of the indescribably bustle crowding of senses and sights and populous vibrancy we associate with India. Lévy Burton knows India well, and this work is another departure from her norm. More intricate, it swings round the hallmark oranges but everything is shrunk and the centre a milky blue-white and above it interrupted by a small orange patch the same: like light, or a relief. Despite its intricacy it’s a balanced work and shows a direction Lévy Burton might take.

‘The Love Affair’ is dominated by a yellow rectangle top left with two legs suspended: the whole effect is of a tripod, and even a small hook added above, to resemble a teapot. Colours that pulse, pinks and reds – and a turquoise near the bottom right, are subordinated by this almost human scale vibrancy, pulsing over the other elements that also include ultramarine sluiced over with white. Nothing challenges this yellow.

‘New day’ built on the same square frame scale, is calmer. It’s bisected across by a thin chain of yellow with her predominantly pink over a red ground, with a small bluish lozenge centre right above the divide. Below are a lime green bar, to its right a compromised red, and to tis right a smaller similarly trammelled blue. Beyond that orange dominates and pulses around more part of a whole than an entity. One might suggest doors to be gone through, but it intimates a series of possible experiences, or indeed a sight of houses on a summer morning. That again is far too concrete and is meant as guide only.

Lévy Burton is herself posed in front of ‘JOY’ an untroubled procession left to right moving from light yellows and blackberry creamed white (a kind of acidic pink, very light-toned) through a fuschia bar to dirty orange encircled in a vibrating yellow, pure cadmium here. There’s a light-blue bar like a signature bottom-centre, delightfully intrusive to the overall palette. A snap of ‘New Day’ again with an untitled and much more thinly-treated canvas (a diaphanous working of pins and yellows and gaze-like orange, tickles the eye. There’s a witty image of a Pollocked floor. I’m glad its quiddity was captured. Crome yellow seems liberally lost.

Finally an untitled masterwork hangs in the gallery’s window. Determinedly bounded in deep orange, this large-scale rectangular painting involves emerald and yellow patterns, with a lost couple of ultramarine rectangles, worked over, above those orange edges, in sweeps of dirty white scumbling over nearly all the frame – above a yellow outburst lower-centre: the effect is a kind of dance of seven or eight veils: these both erase and tease, suggesting distance and unobtainable body, recession of something hidden in shallow ground. But the white stroke are energetic, unsettled, exuberant, quite opposite to the stillness of the deeper colours. The ghosts of things dart, and some of the blur-outs – an exquisite effect lower right towards the orange border as fuschia and white scumble over each other, is masterly.

Lévy Burton’s commented on the spiritual dimension, and India’s influence – her mother was born there and Lévy-Burton has returned many times – are part of an essentially Christian eschatology she explains in some depth. Singing bowls, from te Tibetan Buddhist tradition and many workshops and self-realisations inform both core practice and the grounds of inspiration. Since Lévy Burton is eloquent on these inner states, it’s best to direct the interested reader and viewer to the excellent London Cult article: first-class both in tis coverage, expansive invitation to Lévy Burton, and production values from print to image.

I return to the surfaces, those crusty palimpsests and crests of impasto: the excitement of creation. Most of all the size of the photographs lent the imaged paintings a glow that even a gallery can’t always lend. Especially in the bustle. There’s an extraordinary radiance in the colour – and when you consider the impasto effects, this luminousness is nothing short of astonishing. You can see this in the locking and layering. There’s also no muddy joins, no dull opacity. Partly the bright clarities of acrylic help, but can’t explain Lévy Burton’s gift of balancing – sometimes in an unconsidered sweep – colour contrasts. Without being dragged down to muddy paint-death. It’s perilous, this pristine world, but worth the price of risking – without underpinning, without drawing, without sketches, without a masterplan. That’s why it transcends the need for them.

Very interesting interview! When does the exhibition end? Please visit art’otel London Hoxton to see a solo exhibition by an English sculptor Hermione Allsopp, she uses the notion of everyday in her practice. The show is on until November 22nd. Organised by ADH Gallery.