After a three-year hiatus, Tate Britain has unveiled Rex Whistler’s mural ‘The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meats,’ following intense debates and consultations on the artwork’s future—whether to dismantle, maintain, reinterpret or conserve it.

Brushes to Bytes: Piper and Whistler’s Time-Bridging Exchange

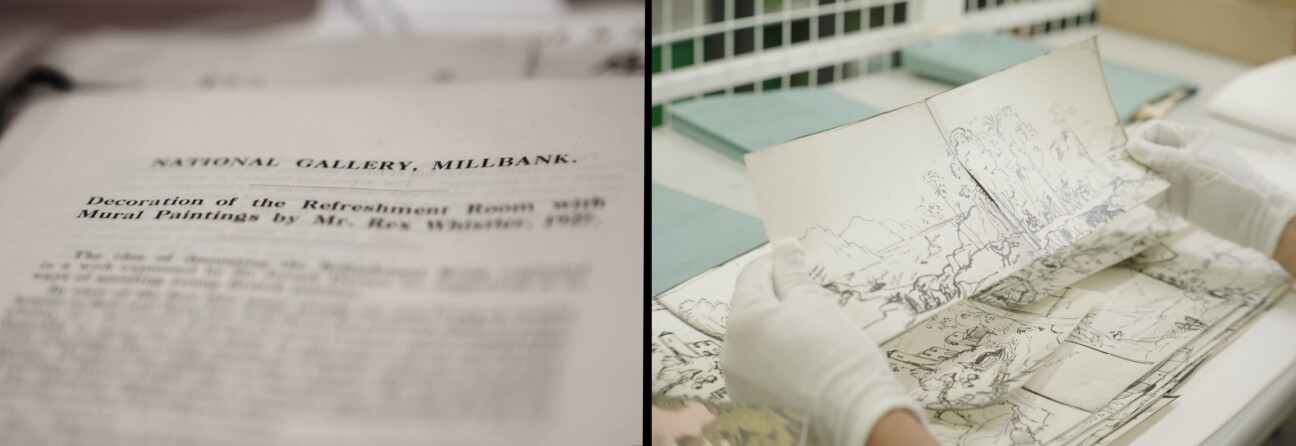

While art may not always adhere to order or logic, this narrative demands them. In 1926, Rex Whistler, then a 21-year-old artist (not to be confused with the one known for portraying his mother so well), received an extraordinary commission for an art student: to decorate the walls of the Tate gallery’s restaurant. Seemingly drawing inspiration from Poussin, Fragonard, and Bellini, he selected a theme that could be characterized as a “phantasmagorical odyssey across diverse locales and architectural wonders.” He crafted sketches and, over 18 months, translated onto canvas a rich tapestry of characters, details, and a plethora of flora and fauna.

For nearly a century, the mural remained largely unnoticed except by art aficionados, and, perhaps, visitors of the restaurant, named afterWhistler. That is until public scrutiny fell upon minute segments of the piece. One fragment depicts a cheerful blonde leading a Black boy with a rope under the watchful eyes of his kin, who, for some reason, has climbed a tree; while another showed Chinese figures in a markedly stereotypical fashion. These scenes, mere centimeters in a vast mural, have ignited controversy. ’Once noticed, they cannot be unseen,’ as remarked by museum director Alex Farquharson.

In 2020, due to Covid-19, the restaurant at Tate Britain closed its doors. By 2022, plans were revealed to complement Whistler’s Hall with a piece by multidisciplinary artist Keith Piper. On March 12, 2024, the space reopened, now showcasing a duo of artistic expressions. Whatdid Piper contribute? He created a two-channel video installation “Viva Voce,” staging a dialogue between Rex Whistler and a modern-day researcher of his work, “professor Shepard” (a discourse possibly conjured in the latter’s imagination, overworked with archival documents). The exchange starts innocuously, with queries about the mural’s origins, Whistler’s social circle, and his artistic inclinations, until a decisive gesture from Shepard brings a controversial figure into focus. “A little humor never hurts,” quips Whistler. Over the next 10 minutes, Shepard schools the artist on racism, dissecting his latent biases and challenging the notion that he was oblivious to the true appearance of African individuals, suggesting an intentional farce in their portrayal. The narrative escalates as Edith Olivier, also resurrected from history, reads her pamphlet (possibly written by Whistlerhimself)—dense enough that only the most ardenthistorical enthusiasts or those of exceptional intellect could comprehend it. “Viva Voce” culminates with footage of World War II, where Whistler volunteered and died in 1944.

Should we now seek insight from Keith Piper regarding the message behind his creation? (It’swell-known that Picasso would shoot blanks at those who dared such questions.) Tate, bound by the responsibility to preserve historical artifacts, was neither in a position to dismantle Whistler’s heritage nor to let it stand unaccompanied by modern commentary. The solution, emblematic of institutional practice, was to commission another artist to recontextualize history. Piper, in this capacity, serves as an interpreter—or perhaps a provocateur—of bygone eras, their deep-seated stereotypes, and prejudices, albeit through a lens that is as conventional as the work he critiques. It’s fascinating to ponder that should “Viva Voce” be enshrined permanently at Tate, it might inspire future artists to layer yet another interpretation, this time uponPiper’s own narrative.