It’s hard to imagine today that children — those endlessly curious little beings with a toy in one hand and chocolate in the other — were once regarded as sources of sin and potential threats to social order. Yet that was precisely how they were perceived in Britain up until the early 20th century. Under the guise of “education” and “moral reform,” actions were taken against children that would now be considered crimes — but at the time, they were known by other names: duty, discipline, tradition.

Cold, Hunger, Isolation: Child-Rearing in Britain’s Past

Opium for Infants

Not so long ago, a popular concoction called Godfrey’s Cordial was widely available in Britain. A sweet syrup made of sugar, opium, and alcohol, it was routinely given to children — to keep them quiet, help them sleep, or simply “just in case.” Cheap and sold over the counter with no restrictions, the syrup was especially common among working-class families. Advertisements claimed it helped mothers keep their jobs without being distracted by crying babies — thus supporting the family.

There were dozens of such syrups on the market. Pharmacies sold bottles labelled “for fretful infants,” each containing enough opium to knock out a grown adult. The consequences — fatalities, addiction, developmental delays — were not yet linked to these “miracle” remedies. It wasn’t until the 1900s that the first steps were taken to regulate their sale.

Silence Chairs and Leather Collars

Victorian schools and orphanages widely employed what was known as “disciplinary furniture” — pieces specifically designed to make children suffer in silence. Among them were wooden chairs of silence — narrow-seated, high-backed, and without armrests. Children were forced to sit in them for hours, often with their hands tied or a book balanced on their head to instil posture and obedience.

Some schools also used leather collars or stiff neck braces that prevented children from turning their heads. If a pupil dared speak or fidget, they could be punished with a whipping, dousing in ice water, or being deprived of food. Reports of such practices survive in the archives of workhouse boarding schools in Yorkshire and Lancashire.

Castor Oil

In 19th-century Britain, castor oil was seen as a kind of holy water by the puritanical education system. Parents, teachers, and wardens in boarding schools believed that any “bad tendencies” in a child — from laziness to stubbornness — stemmed from “internal impurity.” Castor oil was administered not for medical reasons, but for moral and disciplinary purposes — often daily.

There are recorded instances of children being physically restrained, their mouths forced open with metal devices, and the oil poured down their throats. This was especially common in Catholic and Anglican orphanages, where education was equated with cleansing both body and soul. The side effects — vomiting, cramps, dehydration — were seen as signs that the sinful body was being purified.

Children’s Prisons and Treadwheels

Before the introduction of juvenile justice laws, Britain’s legal system made little distinction between adult and child offenders. Children as young as seven could be sentenced to prison and even to death (formally until 1908, though in practice minors hadn’t been executed since the 1830s).

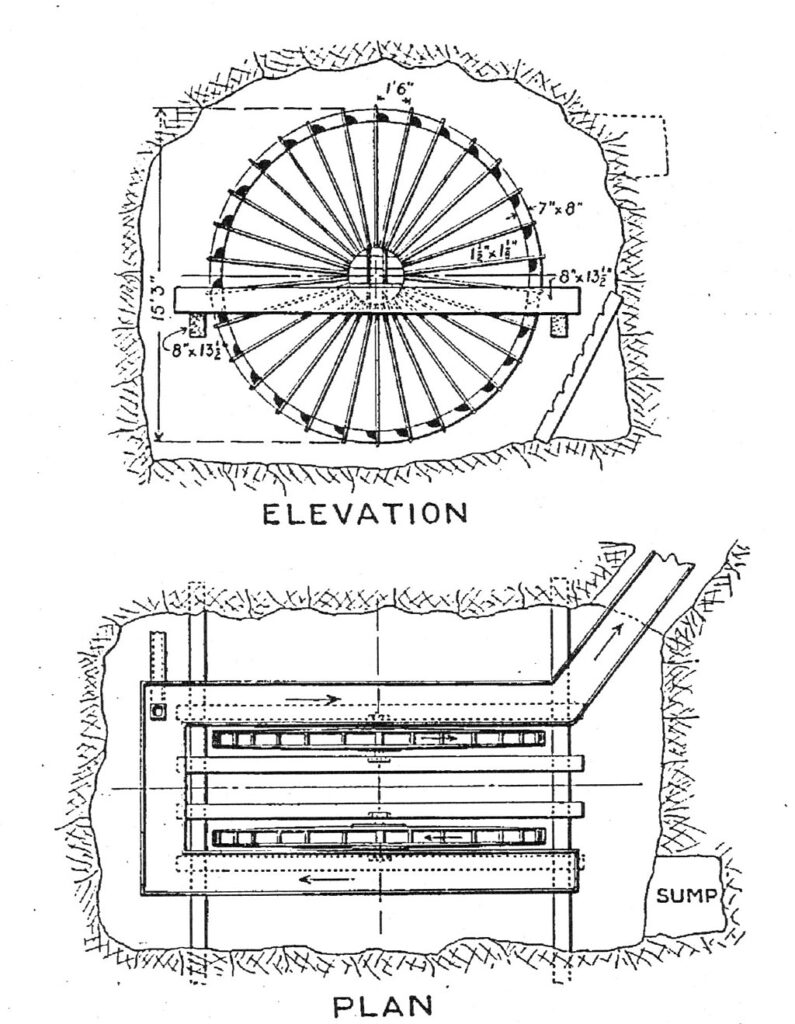

One of the most horrific examples of punishment was the *treadwheel*: a giant rotating wheel that prisoners — including children — were forced to walk on for 8–10 hours a day without pause. Sometimes these wheels generated energy, but more often they served no purpose other than punishment and “disciplinary purification.” Children were housed in the same cells as adults, given the same meagre food, chained, and forced to do hard labor: sorting rags, chiseling stone, or hauling coal.

Religious Orphanages

Many orphanages in 19th- and early 20th-century Britain were run by church organisations. These included so-called *industrial schools* and *reformatories*, which took in orphans, “morally fallen” children (including victims of abuse), and those deemed delinquent by the courts.

In many of these institutions, children as young as six were required to wake at 5 a.m., kneel in prayer for 40 minutes, work 12-hour days in sewing rooms, sleep on bare floors, and eat only porridge and stale bread. Minor misbehaviours were met with beatings, food deprivation, or being locked alone in dark rooms for 24 hours. These schools operated into the mid-20th century and became infamous for widespread physical and sexual abuse.

Cold Affection

Among Britain’s upper classes in the 19th and early 20th centuries, emotional closeness between parent and child was considered harmful. Child-rearing was delegated to nannies and governesses, and parental contact followed a strict schedule — with no physical affection.

Future generals and ministers were raised in environments of rigid emotional control. Parents were taught not to praise, hold, or kiss their children. Hugs were seen as a sign of weakness. As a schoolboy, Winston Churchill wrote dozens of letters begging his mother to visit him at boarding school. In return, he received polite but distant postcards. This emotional distance was believed to cultivate stoicism and resilience — though in reality, it often led to anxiety, emotional detachment, and an inability to express feelings.

When it comes to the treatment of children, Britain’s past was a system built on submission, punishment, and fear — masked as discipline and duty. Many of these traditions are shocking by today’s standards, but it’s crucial to remember: these weren’t fringe practices. They were central to British life.

And sometimes, their echoes remain — in the rigidity of school uniforms, in the stereotype of the “stiff upper lip Brit,” in the ongoing debates about discipline and control. So the next time someone says, “Children used to be more obedient,” you may just understand why.