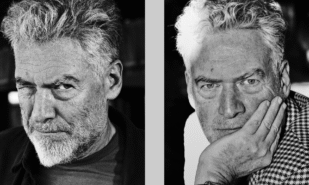

“Much Ado About Nothing” is one of those productions that doesn’t just start at the coat check—it begins right from the theater’s façade. There, bathed in a pink-golden glow, are the enormous faces of Tom Hiddleston and Hayley Atwell—Benedick and Beatrice in Jamie Lloyd’s new staging.

Dawn After the Storm: The Second Play in Drury Lane’s Shakespeare Season

At times, it feels like Jamie Lloyd’s Shakespeare season at Drury Lane isn’t just about theater—it’s a social experiment. But let’s go step by step.

Because, of course, the main event of this production is Tom Hiddleston. He plays to the audience, for the audience, never forgetting for a second that he must earn every penny spent on a ticket. So, transformation? There’s not much—or rather, it’s conditional. This isn’t Shakespeare’s Benedick; it’s the Ultimate, Brilliant Hiddleston, playing Benedick amidst a cast of characters who are, in contrast, entirely Don Pedro and Hero.

This, perhaps, is how comedy looked in the time of Shakespeare and Marlowe—the audience gasping, laughing, and howling with delight while the actor winks at them as if to say, “That was a good one, right? You’d laugh at that, wouldn’t you?” Ha-ha, yes? Aren’t I fantastic?

Lloyd makes Hiddleston dance (unsurprisingly, yes), sing (dear God, at least there’s something this man doesn’t do perfectly, which he himself cheekily admits to the roaring audience), switch vocal registers (including that intimate velvet tone), kiss (front and center stage, passionately, and even for an encore), unbutton his shirt (showing off a sculpted torso, only to button it back up again), leap into a trapdoor and pull himself out with sheer arm strength, dance again (yes… again), get pinned under an enormous inflatable heart, and finally, spit discreetly into a microphone (those ever-present pink confetti scraps keep getting into his mouth, forcing him to spit them out before speaking).

Now, if Hiddleston’s charm doesn’t work on you, all these finely aimed Lloydian arrows will whizz harmlessly past. But that only makes it more fascinating to watch as the actor, director, and ensemble weave an irresistible pink web, drawing the audience in and bending them to their fiery Shakespearean will.

Against this backdrop, Hayley Atwell holds her own with unwavering confidence. She is stunning in every sense of the word. Incredibly beautiful and striking (don’t argue—this whole play is an ode to playful objectification), she firmly steers charming Benedick through the stormy pink sea. This is a performance that demands immense self-restraint, but it pays off tenfold: she is Beatrice, wholly and completely. There’s no question why this Benedick falls for her—just look at her! What actress could withstand such a co-star? Now we know.

Every gesture, every smile from Hiddleston elicits an adoring “Awww!” from the crowd. At times, an indecent question arises—does the play even matter here? Or, like in that old joke, would it be enough if he just paced back and forth on stage? But, of course, the play does matter.

The rest of the cast exists to build up this king and queen, and that is their primary function (though each role is meticulously crafted, every performance honed to a razor’s edge of manic, over-the-top farce—like those damned pink confetti scraps that finally spill over the proscenium, covering the audience in a uniform layer. One wonders if the janitors get hazard pay).

This theatrical (or social?) experiment ends with the bows, where Hiddleston, with just the crook of his pinky finger, brings the 2,000-strong Drury Lane crowd to its feet. Literally. He simply steps to the edge of the stage and makes a tiny movement. The orchestra seats, balconies, and boxes rise simultaneously, a sound more electrifying than a stadium roar after a winning goal.

The cast takes four (spelled out: four!) curtain calls—an anomaly in modern London theater—and it feels like the audience would have pulled them out for a fifth if given the chance.

But Lloyd wouldn’t be Lloyd if this were just a Tom Hiddleston showcase.

Let’s go back to the beginning. After Much Ado About Nothing, it becomes evident that Lloyd’s two-part season is an experiment. A social experiment through theater. That is, he allows the audience to explore their own reactions, while he himself studies the ways in which a production can manipulate them.

In this experiment, there are no “right” or “wrong” paths, no “good” or “bad” emotions. All responses are equally valid—as long as they work.

Boredom or exhilaration, indifference or intrigue, sorrow or joy, disgust or uncontrollable laughter—it’s all the same. What matters is that it works.

Let’s not forget: both critics and audiences were unimpressed by The Tempest with Sigourney Weaver, finding much to criticize. But the production’s restraint, Weaver’s peculiar performance, her engagement with the audience, her constant presence on stage (not once did she step off)—it was all clearly part of Lloyd’s directorial vision. A rather merciless one, at that.

The ensemble, in a near-repertory-theater fashion, carried over almost entirely from one play to the next. This, too, is an experiment (at least in contemporary British theater), and an absolutely thrilling one—to watch an entire season unfold with the same actors under the same director.

The youthful romantic couple transitioned from The Tempest to Much Ado seamlessly: the vivacious Mara Huf (Hero) and the gentle, Chaucerian James Phoon (Claudio). Pure delight for theater scholars.

Forbes Masson—grotesquely deformed as Caliban—here plays the tragic father, Leonato, alternately heartbroken and devoted. A strange but understandable character parallel.

It feels like Lloyd draws his narrative connections with a permanent marker and a ruler: here’s the island, here’s Messina; here’s a ship full of drunken sailors, here’s a troop of rowdy soldiers.

But what most vividly unites the two productions is a single character—or rather, they. Mason Alexander Park, who played Ariel in The Tempest, now takes on the seemingly minor role of Margaret, one of the ladies-in-waiting in Much Ado.

Like narrators and witnesses, they dart across the stage, flying, singing, jumping—filling every space they enter like gas. Park is still Park—or rather, a theatrical genius, pure kinetic energy. You could even call them electricity. They flow according to their own laws and possess an ambivalent force. Hilarious one moment, then suddenly, from those sharply lined eyes, a gaze of unfathomable darkness.

It is Park’s characters that stitch these two productions together into a single whole, transforming them into a diptych.

A gray tragedy and a pink comedy. The smoke and fog of Prospero’s island evoke unrelenting sorrow, while Leonato’s Messina is so sugary sweet that you almost wish the concession stand sold pickles instead of ice cream at intermission.

Two plays—two poles, like the positive and negative ends of a massive battery, fueling Jamie Lloyd’s Theatrical Company.