Director is Satisfied: Dario Argento’s “Dark Glasses” – Did You Want Some Evil?

The foundation of a successful giallo—a genre born from the fusion of horror, detective, and kitsch—is erotica and gore. Both elements are somewhat lacking in the latest film by Dario Argento, the father of giallo. Unless one considers the various manifestations of red—in clothing, bathrobes, lipstick, and the awnings of Roman balconies and cafes—as a subtle inversion of the genre’s bloody tropes.

A predatory maniac stalks the Eternal City’s elite escorts, prowling around in a van. One fateful evening, in true giallo fashion, he claims a victim. Simultaneously and rather fortunately, Diana (Ilenia Pastorelli), having just declined a client’s request for fisting,gets into her car on a nearby street. The ensuing chase through Rome’s desolate streets culminates in a crash, leaving Diana blind due to a hemorrhage in her brain’s Brodmann area (among other perverted interests, Argento has always had a penchant for medical terminology). The accident also orphans young Chin, who, after a brief stay in an orphanage, runs away to “Aunt Diana.”

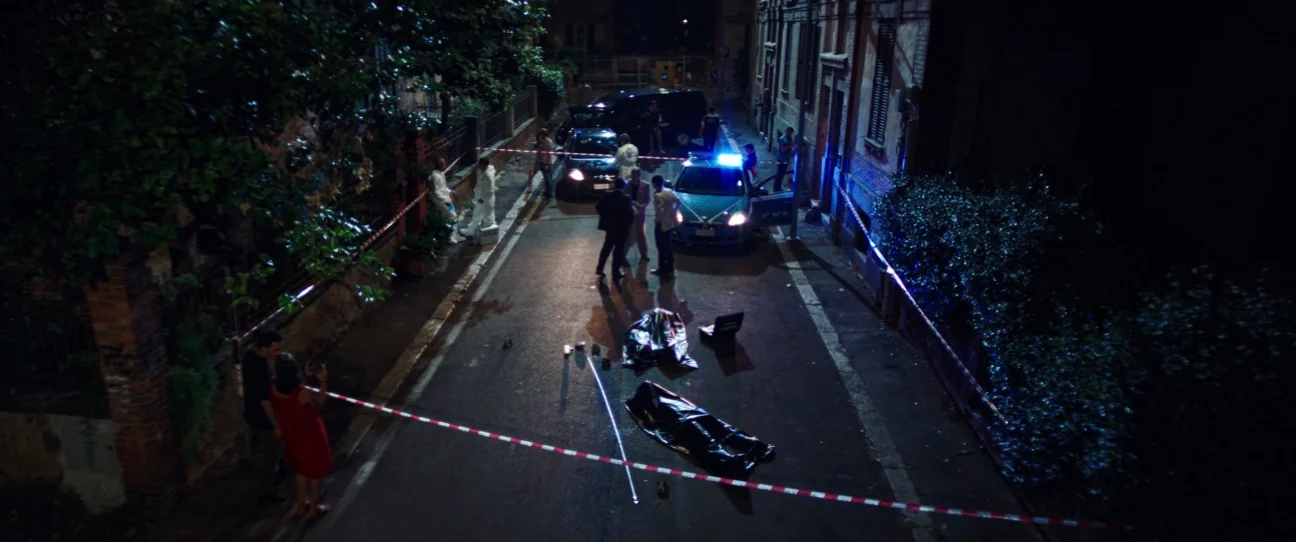

Around this juncture, or perhaps slightly earlier, with the introduction of Asia Argento—the maestro’s daughter—in the supporting role of Rita, a volunteer assisting Diana in selecting a guide dog, the giallo mutates, for a considerable stretch, persisting almost until the climax, into a melodrama. Under these newconditions, it is not so much Diana looking after Chin as the boy assuming a mentor-like role: ‘My sister in Hong Kong did the same thingas you, she always had lots of money and la pistola.’ Consequently, there remains littleroom for the maniac or occult justifications for violence—the murders are reduced to a set of happenstances tinged with luck. Yet even so, the police remain powerless, they can only shake their heads in disbelief, document the atrocities, and leave to await the next victim.

After the release of “Dark Glasses,” Argento was critisized of excessive melodrama, a dulling of giallo’s tools, a dearth of moral depth in conception, and glaring plot holes. Critics,worth their salt, attributed these flaws to the director’s advancing years. However, the real issue with devaluing artistic decisions based on the author’s age lies not in its frequent irrelevance, but in the absence of an equivalent biographical scrutiny of the critics themselves. Sophisticated dramaturgy and meticulous psychological portraits were never the forte of Argento—an independent, eccentric auteur who follows the discordant rhythms of logic’s dark underbelly. If this approach leads him to place Chin, a boy who claims to have relatives in Hong Kong, in a Catholic orphanage—so what?

‘Neither the sun, nor death, nor logic can be looked at directly’—thus should the quote from “some French writer” appearing in the film be extended. While “Dark Glasses” has itsimperfections, it boasts an utterly brilliant integration of Arnaud Rebotini’s electronic score—ranging from spine-chilling synths to 130bpm techno, a metronome for the unfolding drama—into the narrative’s dynamics. The film also presents a chemistry within the triangle of Diana, Chin, and Rita that, while perhaps caricatured for giallo, proves effective (potentially evolving into a square if weattempt to arrange an additional corner for the guide dog). Furthermore, there are mythologicalreferences, though simple, to the goddess Diana and her canine protectors. Finally, there’s the climactic escape from the maniac, with the sudden appearance of water beasts at the most inopportune moment.

“Dark Glasses” is certainly not a Colosseum of fear constructed in Argento’s signature works, yet it’s quite an impressive attraction that doesn’t look at all anachronistic. No matter what year it is outside: for those who might confuse ‘giallo’ with ‘gelato,’ unfamiliar with Argento’s work, “Dark Glasses” offers a worthyalternative to cookie-cutter American post-horrors.