Since May 24th, Damien Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery has been the stage for the Dominion exhibition, curated by Hirst’s son Connor. This exhibition is primarily composed of Hirst’s own collection—a formula that is quintessentially Hirst. The roster alone commands attention, featuring works by Francis Bacon, Banksy, Georg Baselitz, Jeff Koons, and Hirst himself. Dominion occupies six spaces within the gallery, which was converted in 2015 from several Victorian-listed buildings.

Dominion at Newport Street Gallery

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Category | Columnists, Culture, Lifestyle, People, Town |

| Date | June 11 2024 |

| Reading Time | 3 min. |

Dominion at Newport Street Gallery

On the right: Stop & Search Basquiat by Banksy

Upon crossing the threshold, visitors are greeted by Marcus Harvey’s Myra, a standout from the 1997 Sensations exhibition by the Young British Artists at the Royal Academy. The canvas is paved with patterns using casts of a child’s hand, collectively forming the infamous portrait of Myra Hindley, the Moors murderer convicted in 1965 for the brutal slaying of five children. This piece replicates the starkness of a black-and-white newspaper photograph of ‘England’s most evil woman.’ The work’s fusion of concept, execution, and subject matter earned it scandalous renown, showcasing how art had the capacity to strike a social nerve some 30 years ago.

On the right: Bunny by Sara Lucas

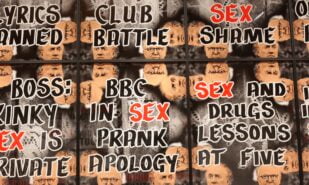

Each subsequent hall features at least one Banksy on a spectrum of surfaces—from classic canvas to road sign—each piece narrating rebellion: Madonna poisoning her Child, Lenin on roller skates. Richard Prince contributes his iconic cowboy and nurse motifs—the latter an emblem of 20th-century culture, with its sexual charge explained by the artist as stemming from the profession’s proximity to both life and death. The raw materiality and primordial expression of Keith Cunningham’s Yellow Monkey and Four Bulls anchor in the avant-garde ethos of the 1960s, a time shared with Francis Bacon and Frank Auerbach.

On the right: Transit Disaster Diptych by Gavin Turk

The exhibition includes works by Hirst’s early associates, Mat Collishaw and Sarah Lucas, participants in the pivotal YBA’s Freeze and Sensations exhibitions. As if to confirm the notion that Collishaw’s oeuvre is experienced on the borders of the attractive, filthy, and indecent, his Burnt Almonds, Rudolph and Gisela stands next to a sign warning of sensitive content—a relevant notice for the entire exhibition.

Among the eighty exhibits, only two—the skulls presiding over each floor of the gallery—are accompanied by annotations with historiographic references. To identify the remaining works, one must refer to the printed plan. Whether the lack of elucidation is intentional or not, it emerges as perhaps the exhibition’s most triumphant aspect. These archaeological artifacts (with one of the skulls pierced by an iron spike), nestled within an environment of ostensibly informal art, are steeped in irrationality—if such a definition is fair and applicable to osseous remnants. Simultaneously serving as a Memento Mori, they oscillate between mockery and solemnity. Through the hollow gaze of these skeletal sentinels, Damien and Connor themselves could be surveying their audience.

The artworks are arranged across the rooms by stylistic attributes: reds beside oranges, florals with patterns, etc. The presence of an overarching, foreground conceptual thread is not readily discernible, and it is doubtful that one was ever intended. Most pieces, while meritorious in their own right, become a challenge to appreciate in isolation: the overall coherence is roughly calibrated, at times too loud, at others indistinct, often blending into a backdrop of artificial white noise that pushes individuality to the periphery.

Dominion, true to its name, is an exhibition of distilled essence—a grand yet utterly optional abstraction that pays only lip service to the sovereignty of art but is poised to break away and assert its own defiant identity. Whether this identity will be defined by kitsch, irony, ecstasy, carnal triumph, confusion, or a fusion of these, Damien Hirst could express the idea behind Dominion in his characteristic manner of reducing any subject to the level of a joke. As two men approach a black-and-white portrait at the exhibition, one asks the other: ‘What does this mean?’ To which the black-and-white portrait replies: ‘And what the **** do you mean?!’