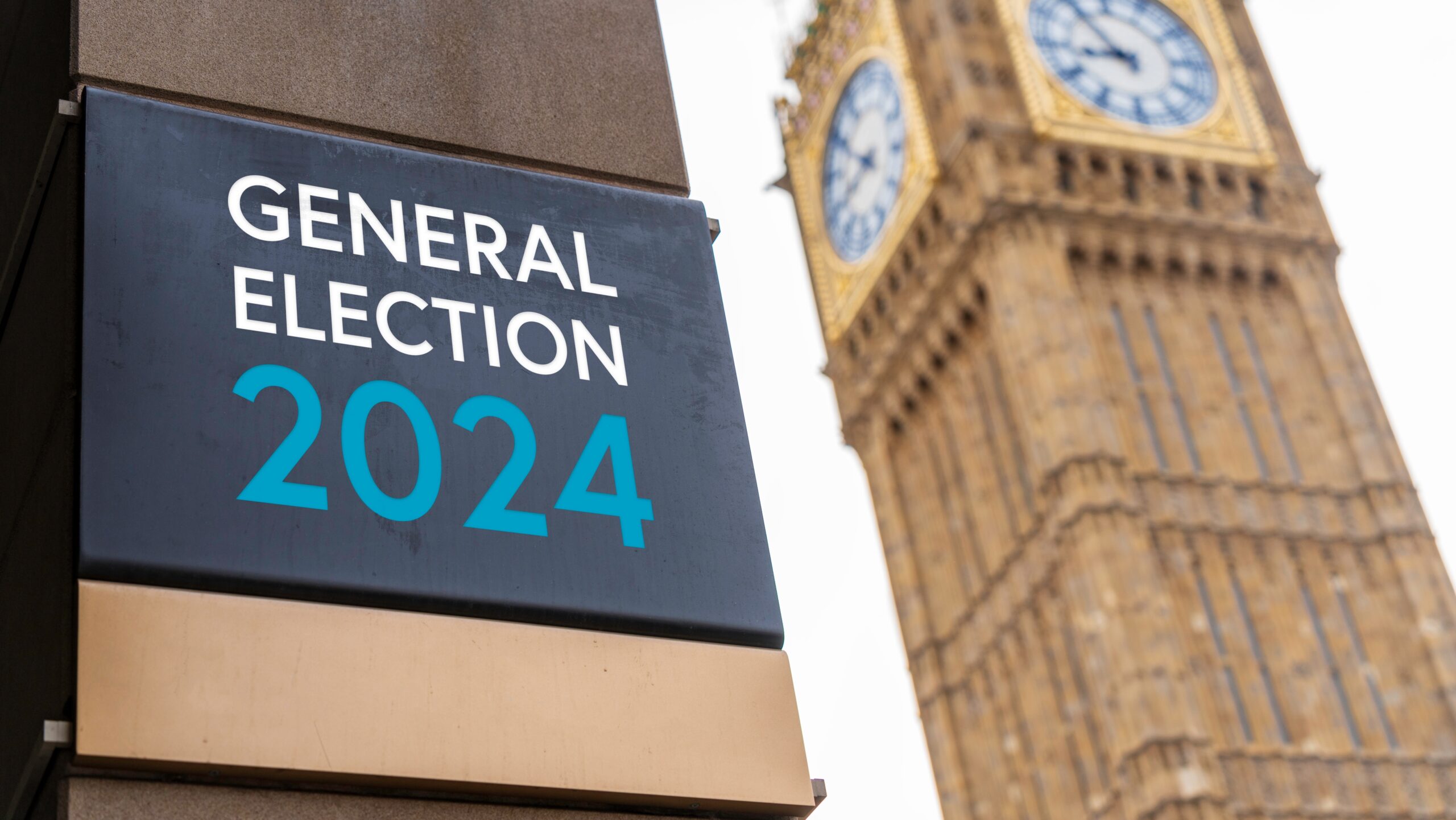

Elections 2024: Why Now and What’s at Stake?

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak suddenly announced the holding of general elections on July 4, 2024, which means one thing: in the next two months, we can expect fierce political battles. Sunak’s announcement, made in the rain outside Number 10 Downing Street, signalled a turning point for the United Kingdom. This move came after a period of growing pressure from the Labour Party, which had been demanding elections for over a year, and amid internal issues within the Tory party. Despite all this, the announced date surprised the public, the media, and Sunak’s Conservative Party.

Why Now?

Many expected that trailing Labour by 20 points, Sunak would delay the elections until October-November. This would align with the Tories’ idea that their economic program “just needed time.” However, recent signs of nominal economic improvement and the finalisation of the immigration programme involving Rwanda likely influenced his decision. Sunak saw a window of opportunity: inflation had dropped from a peak of 11.1% in October 2022 to 2.3% in April 2024, and the economy grew by 0.6% in the first quarter of 2024 after a shallow recession. The Prime Minister stated, “We live in uncertain times, and those uncertain times call for a government that is prepared to take bold action, that has got a clear plan.”

Therefore, according to Bronwen Maddox, director of the Chatham House think tank, Sunak is rushing the elections because he fears that favourable economic conditions won’t last long.

So, deciding to deal with the elections as soon as possible seems quite logical: if he wins, Sunak will remain in power, and if he loses, he will find new opportunities for himself and his family wealth (which, by the way, has grown by 120 million to 651 million pounds). By scheduling the vote now, the Prime Minister aims to control the course of events. Additionally, the government’s sudden move caught the opposition off guard.

What Are The Key Pledges?

Regardless of motivations and behind-the-scenes maneuvers, the general elections will take place, and two main, long-known opponents will face off. The Liberal Democrats, Reform UK, and the Greens are in the race too, of course. But it’s the Conservatives and Labour who have real chances of winning. Each party has one goal: to convince voters that they, not their opponents, can fix the country’s problems—from the economy to the environment. So, what measures are both parties promising to take if they win?

1. Economic Policy: Diverging Views

For both parties, the economy is a central focus. For Conservative voters, Sunak’s administration has emphasisedthree key priorities: reducing inflation, growing the economy, and cutting public debt. And it seems Sunak has some right to claim certain successes here. However, the Institute for Fiscal Studies has questioned the government’s achievements, attributing the victory over inflation mainly to the Bank of England’s policies.

In response, Labour hasn’t missed the opportunity to criticisethe Conservatives’ 14-year economic management. Starmer, in turn, has promised voters a new approach to the issue, called “securonomics”: strict fiscal rules, the creation of an Office for Value for Money, and reducing spending on consultants. Labour also proposes introducing a “COVID Corruption Commissioner” to recover funds lost due to numerous cases of contract fraud during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For both parties, the economy is a central focus. For Conservative voters, Sunak’s administration has emphasisedthree key priorities: reducing inflation, growing the economy, and cutting public debt. And it seems Sunak has some right to claim certain successes here. However, the Institute for Fiscal Studies has questioned the government’s achievements, attributing the victory over inflation mainly to the Bank of England’s policies.

In response, Labour hasn’t missed the opportunity to criticisethe Conservatives’ 14-year economic management. Starmer, in turn, has promised voters a new approach to the issue, called “securonomics”: strict fiscal rules, the creation of an Office for Value for Money, and reducing spending on consultants. Labour also proposes introducing a “COVID Corruption Commissioner” to recover funds lost due to numerous cases of contract fraud during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Taxation: Reluctance to Raise Taxes

Regarding taxes, both parties are demonstrating a cautious approach. Labour has stated they will not reverse the Conservatives’ 2p reduction in national insurance but will instead eliminate the “non-dom” tax status, tax private schools with VAT, and crack down on tax evasion. In response, the Tories have advocated for the gradual elimination of the “non-dom” status without alarming the concerned electorate with sudden changes.

Regarding taxes, both parties are demonstrating a cautious approach. Labour has stated they will not reverse the Conservatives’ 2p reduction in national insurance but will instead eliminate the “non-dom” tax status, tax private schools with VAT, and crack down on tax evasion. In response, the Tories have advocated for the gradual elimination of the “non-dom” status without alarming the concerned electorate with sudden changes.

3. NHS: Ready for Labour and Defence

Waiting times in the NHS have only increased recently (for instance, at the end of 2023, 7.8 million people were waiting for treatment). The Conservatives blame these delays on the COVID-19 pandemic and promise record funding and an increase in medical staff. However, the Institute for Fiscal Studies provides a pessimistic forecast: a real increase in the NHS budget is unlikely. Labour, led by Shadow Health Secretary Wes Streeting, is ready to reduce staff workload by creating new jobs and offering 40,000 additional weekly appointments in the evenings and on weekends.

Waiting times in the NHS have only increased recently (for instance, at the end of 2023, 7.8 million people were waiting for treatment). The Conservatives blame these delays on the COVID-19 pandemic and promise record funding and an increase in medical staff. However, the Institute for Fiscal Studies provides a pessimistic forecast: a real increase in the NHS budget is unlikely. Labour, led by Shadow Health Secretary Wes Streeting, is ready to reduce staff workload by creating new jobs and offering 40,000 additional weekly appointments in the evenings and on weekends.

4. Immigration: Diverging Strategies

Immigration has always been and remains the most contentious issue of all. The Sunak government’s hardline stance includes a 12-point plan aimed at reducing migration from 606,000 people in 2022 to 240,000 people in 2024. However, the results have been mixed: in early 2024, a record number of migrants crossedthe Channel. Labour proposes an immigration system based on a points system, inspired by the Australian model, and plans to create a Border Security Agency and a Removal Unit to expedite the deportation of those denied asylum.

Immigration has always been and remains the most contentious issue of all. The Sunak government’s hardline stance includes a 12-point plan aimed at reducing migration from 606,000 people in 2022 to 240,000 people in 2024. However, the results have been mixed: in early 2024, a record number of migrants crossedthe Channel. Labour proposes an immigration system based on a points system, inspired by the Australian model, and plans to create a Border Security Agency and a Removal Unit to expedite the deportation of those denied asylum.

5. Environmental Policy: Bright Future Ahead

Both parties have committed to the goal of reaching net zero emissions by 2050, but their approaches differ. Sunak’s administration supports a ban on the sale of diesel and petrol cars and aims to transition everyone to electric vehicles by 2035. They also advocate for shifting from gas boilers to heat pumps. Labour’s strategy includes creating “Great British Energy,” a state organisation aimed at reducing electricity bills and creating jobs, funded by a windfall tax on oil and gas companies’ profits.

Both parties have committed to the goal of reaching net zero emissions by 2050, but their approaches differ. Sunak’s administration supports a ban on the sale of diesel and petrol cars and aims to transition everyone to electric vehicles by 2035. They also advocate for shifting from gas boilers to heat pumps. Labour’s strategy includes creating “Great British Energy,” a state organisation aimed at reducing electricity bills and creating jobs, funded by a windfall tax on oil and gas companies’ profits.

6. Education: Many Plans, All Different

Labour prioritises education by planning to hire 6,500 new teachers and implement a “national retraining program” for continuous professional development. They also intend to review and expand the national curriculum. The Conservatives propose introducing the “Advanced British Standard” qualification for 16-18-year-olds, increasing the number of A-level exams from 3 to 5, and ensuring the study of math and English until age 18. This plan is supported by significant funding but faces resistance from teachers’ unions, who continue to strike over pay and working conditions.

Labour prioritises education by planning to hire 6,500 new teachers and implement a “national retraining program” for continuous professional development. They also intend to review and expand the national curriculum. The Conservatives propose introducing the “Advanced British Standard” qualification for 16-18-year-olds, increasing the number of A-level exams from 3 to 5, and ensuring the study of math and English until age 18. This plan is supported by significant funding but faces resistance from teachers’ unions, who continue to strike over pay and working conditions.

July 4 elections will be historic, regardless of outcome. Hannah Bunting, a lecturer at Exeter University, noted, “I think it is going to be an election that we are talking about for quite some time.” According to her, Labour needs to gain 12.7% of the vote to secure a parliamentary majority. While they are significantly ahead of the Tories, this percentage is much higher than what Tony Blair achieved in 1997, one of the most popular Labour prime ministers. Additionally, recent local elections have shown not so much a Labour advantage as the potential of smaller parties and independent candidates, which also casts doubt on the certainty of a Labour victory.