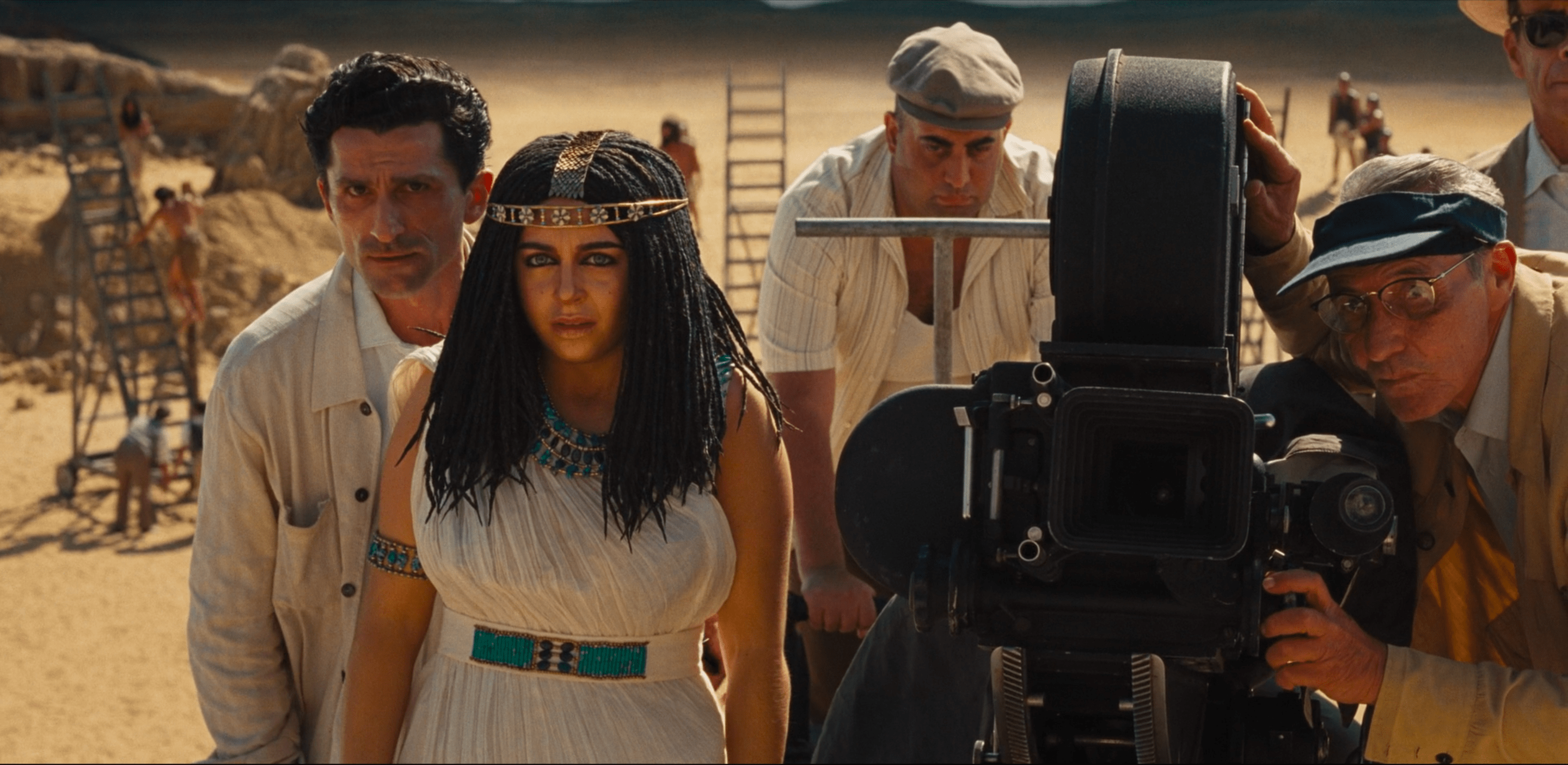

Transporting the viewer to the legendary premises of the Cinecittà studio near Rome, “Finally Dawn” nostalgically harks back to the 1950s. The narrative unfolds with a classic setup of a Cinderella-like transformation in a fairy-tale world: accompanying her sister to a casting call for an American epic reminiscent of “Cleopatra” and “Ben-Hur,” 19-year-old Mimosa (Rebecca Antonaci) catches the eye of the film’s leading star, Josephine Esperanto (Lily James). However, the unexpected role she lands, coupled with the malicious gossip of less successful extras, only serves to amplify the insecurities of the poor girl.

“Finally Dawn” by Saverio Costanzo: An Unrealized Thriller, A Nostalgic Fairy Tale

As the shooting concludes, the helpless and somnambulistic Mimosa, lost in the labyrinthine Cinecittà, stumbles upon a limousine carrying the aloof siren Josephine, her introspective partner Sean Lockwood (Joe Keery), and the kind-hearted art dealer Rufus (Willem Dafoe). The company takes Mimosa under their wing, whisking her away to a villa teeming with a demi-monde of influential philanderers, artists, patrons, and ordinary bon vivants. Josephine introduces her protégé as Sandy, a promising Swedish poetess, though it’s unclear how Mimosa relates to yetanother identity shift of the day, as she maintains only two facial expressions throughout the film: stunned and stunned-pleased. Thus, the unfamiliar attention from the public seems to genuinely stun her.

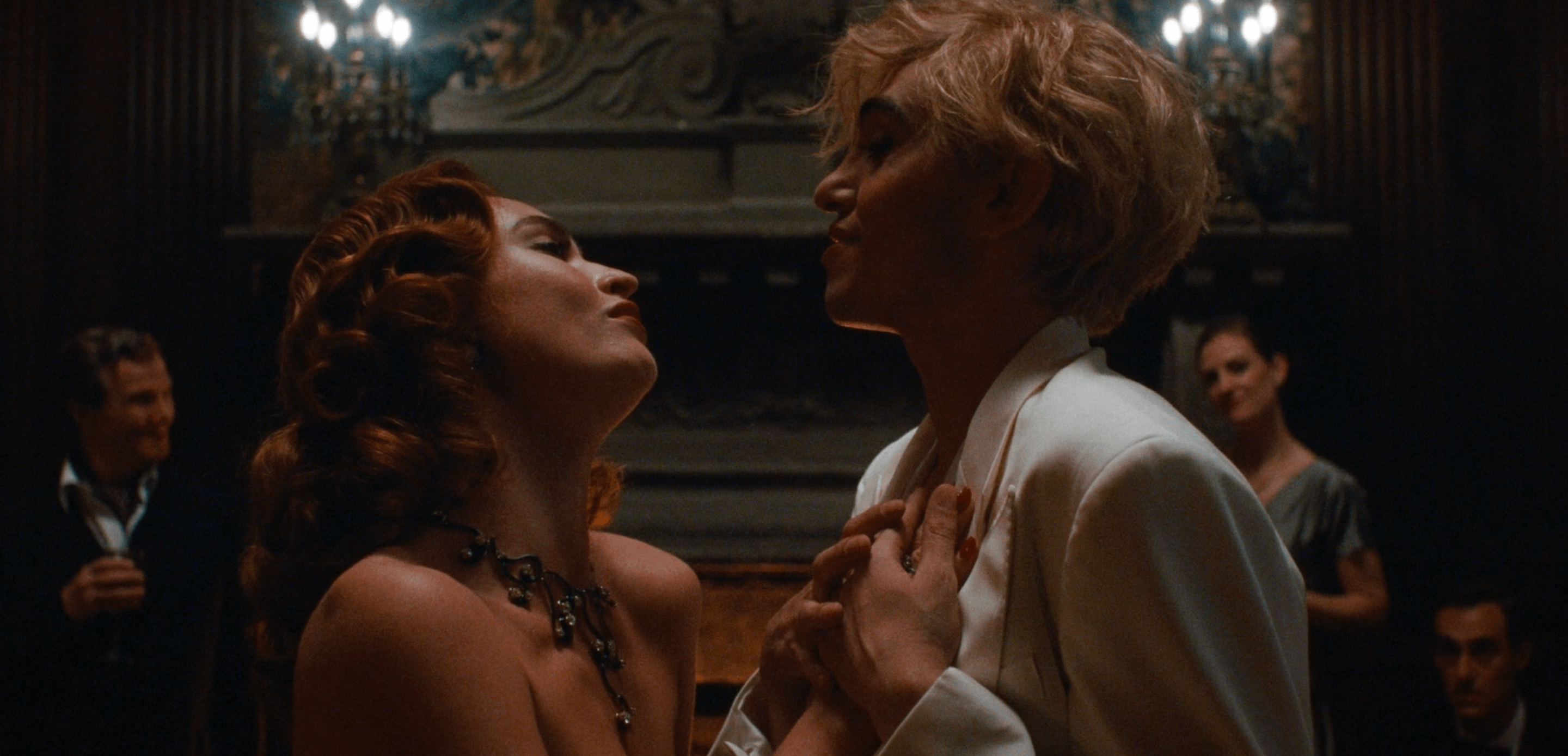

Josephine, having had her fun, callously discards her plaything to the wolves—she proposes the “poetess” to recite her latestcreations. A tense silence ensues, and instead of verses, to spite her tormentor, Mimosa drops a few tears—a performance that deeply moves and pleases the crowd. Immediately, she is offered patronage, with a publisher practically begging her to sign a contract, and no one questions why this “Swede” is short, curly-haired, and dark-skinned.

The initial three-quarters of the film pass, with an escalating rhythm and a retro charm make it quite engaging to watch. However, as the plot becomes increasingly tethered to the caprices of its characters, it loses momentum, bogging down in an interminable night. During this nocturnal odyssey, Mimosa undergoes various rites of passage (a spark of attraction ignites between her and Sean)—a night of maturation that,frankly, makes growing up seem rather undesirable. The finale, with the dawn, features the baffling appearance of a CGI–lioness, seemingly escaped from Cinecittà and animated with a dated smartphone app, parading alongside the protagonist through the streets of the Eternal City. This overused symbolism, orFellinism, is generally the main issue withSaverio Costanzo, from whom audiences continue to expect performances on par with those of Sorrentino and Guadagnino.

In truth, one could easily overlook this far-from-harmonious film if it weren’t for its meticulously conveyed cinematic atmosphere which, though pretentious, manages to sustain states of suspense, anticipation, attention, and sensuality. What was likely conceived as a poetic homage to the old Cinecittà is, in essence, a fairy tale, replete with sham, overwhelming gloss, caricatured characters, and a too-narrow perspective. Somehow this fairy tale serves as a metaphor for an eternal night—the sensation experienced every time one entersa cinema. Following “The Solitude of Prime Numbers” and “Hungry Hearts,” Costanzo has crafted another uneven film, this time with exceptional charm (but lacking character), which you admire until the end, following its lead, only to later chide yourself for such naivety.