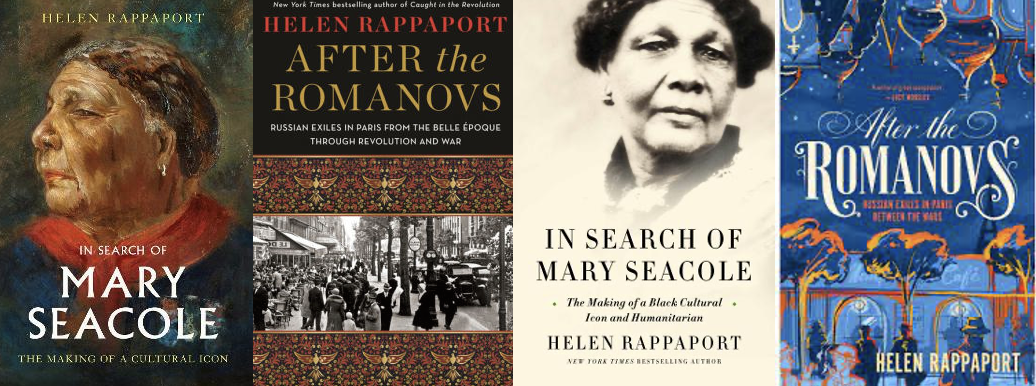

Helen Rappaport is a historian specialising in the Victorian period, with a particular interest in Queen Victoria and the Jamaican healer and caregiver, Mary Seacole. She also has written extensively on late Imperial Russia, the 1917 Revolution and the Romanov family. Her love of all things Victorian springs from her childhood growing up near the River Medway where Charles Dickens lived and worked. Her passion for Russian came from a Russian Special Studies BA degree course at Leeds University. In 2017 she was awarded an honorary D.Litt by Leeds for her services to history. She is also a member of the Royal Historical Society, the Genealogical Society, the Society of Authors and the Victorian Society. She lives in the West Country, UK.

From Stage to Study: The Remarkable Journey of Helen Rappaport, Historian and Storyteller

Helen, I saw that you started your career as an actress. How did your life, your experience, your education lead you to becoming a writer. You would become very prolific in future – what was the pathway to this career?

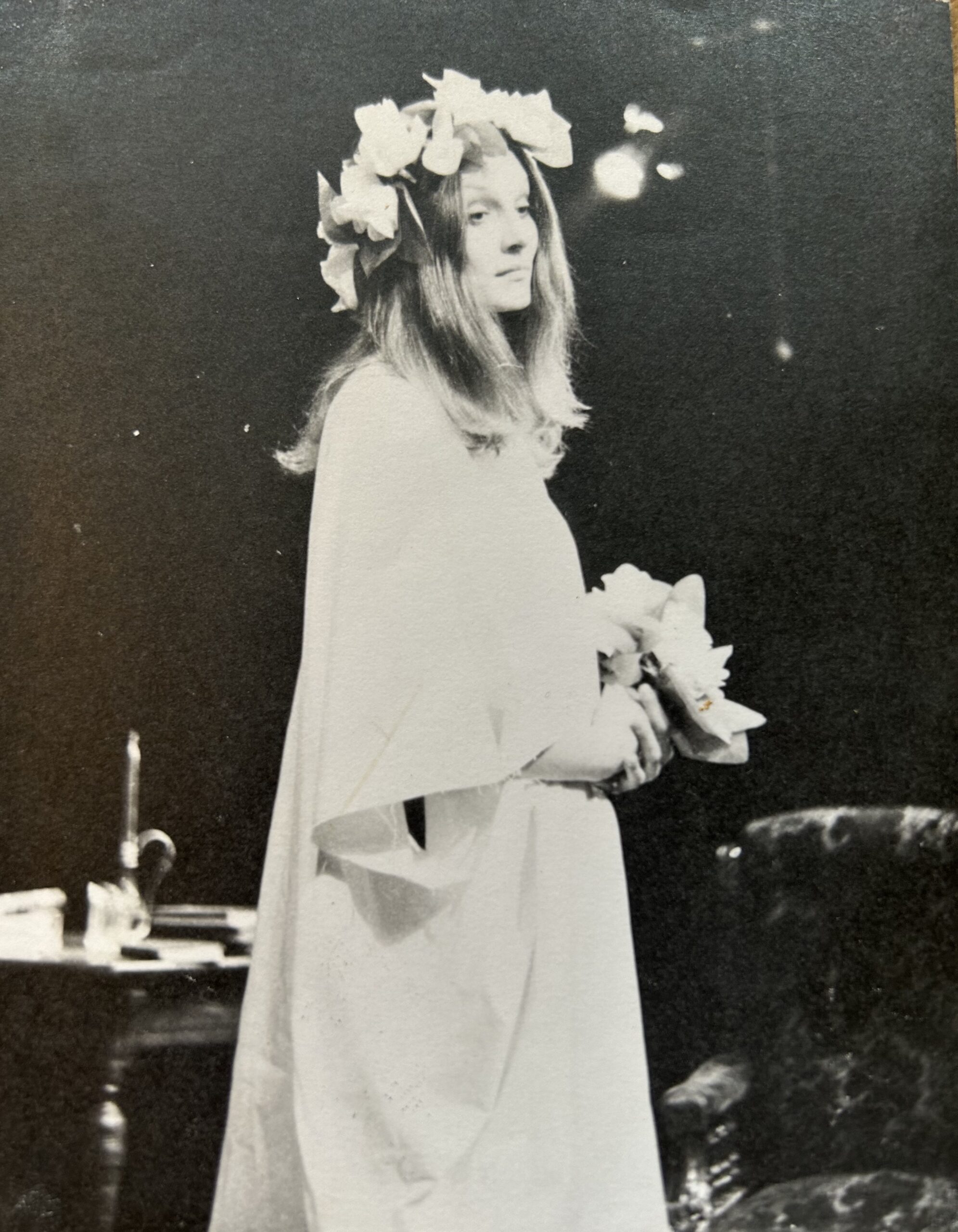

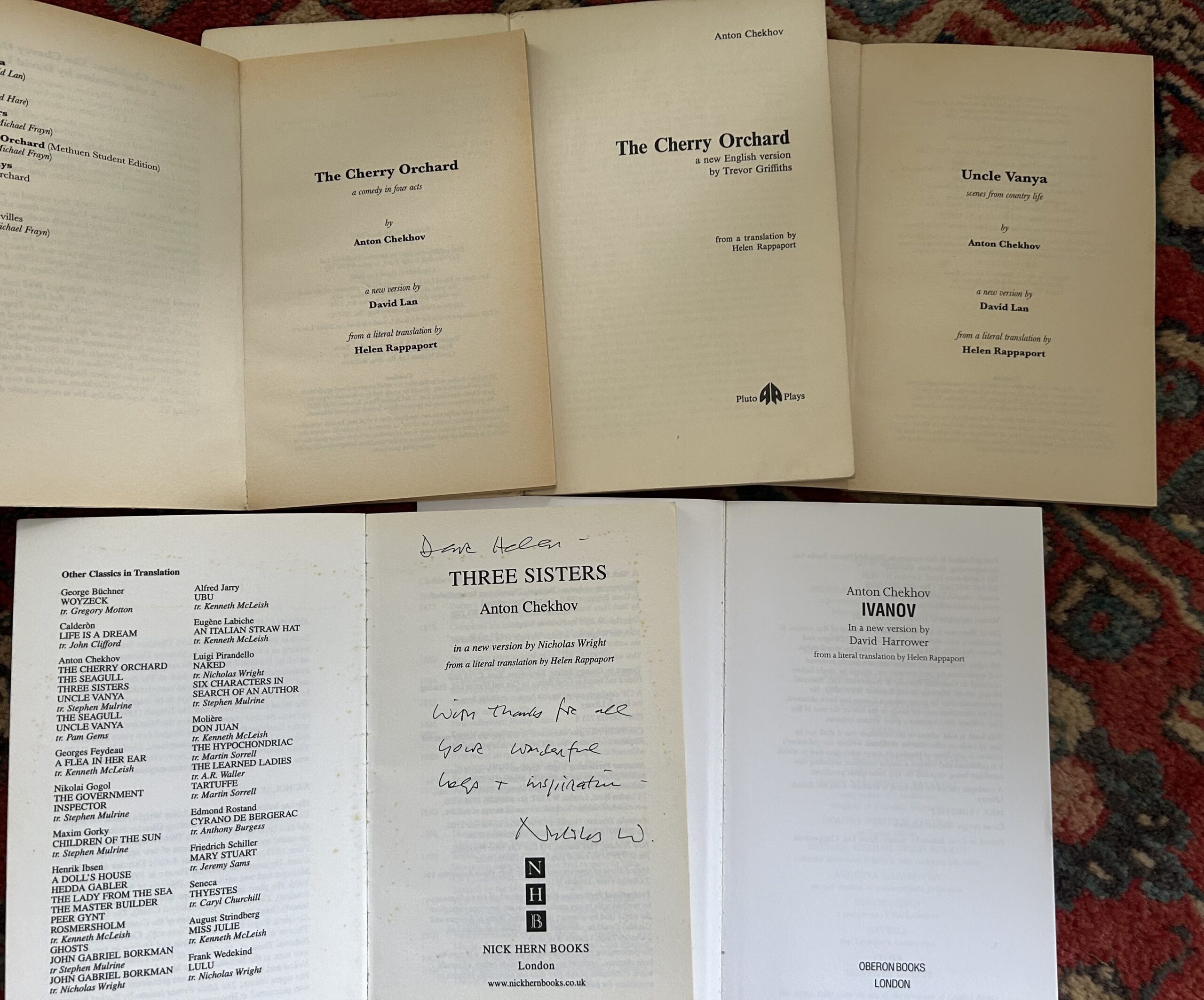

Well, I’d always loved history, I’d loved history as a teenager. So I was very absorbed in it, especially in the Victorian period, in Charles Dickens. I loved the Victorians. But in my teens I discovered the Russians. I discovered Chekhov and Tolstoy, and I absolutely fell in love with Russian literature, music, and art. And after doing my A-levels at school, I went to university to study Russian and did a very intensive four-year course in Russian special studies, for which I am very grateful. It was a wonderful degree course. You can’t get that kind of course anywhere now in the UK. The standards have gone right down. It was a fabulous course. I spent three months as an exchange student in Sofia and studied Bulgarian as well as part of it. But during university, I got very heavily involved in student theatre and was in a lot of plays, and one of them was Chekhov. I was in two or three Chekhov plays actually, including The Seagull, which I loved so much. I got completely bitten by the acting bug.

And acting is one of those things – once you kind of get bitten by it and feel you want to do it, you have to do it. But then you move on and do something else, which is exactly really what happened to me. I always loved history, I’ve always wanted to write history. So after coming out of university, when everyone was saying ‘You’re going to join the foreign office, aren’t you, are you going to be a spy, are you going to go to MI6?’… Obviously in those days when you studied Russian, people assumed you were a screaming communist, and you were pro-Soviet, which wasn’t it at all. I studied Russian because of my love of the culture and the language. So Ii said no, I want to be an actress, which of course is a terrible, fatal thing to say (laughing). So when I came out of university, I tried to break into the acting profession on and off for about 15 years. I did get work, but the trouble with acting work, especially for women, is that there’s far less work for women, now probably even more so than it was, because there are less programs and also because now diversity plays such a strong part in it all, and there are fewer and fewer parts anyway, for white women especially. I struggled. The trouble with acting is that you spend an awful lot of time waiting to get work, being unemployed, doing fill-in jobs which are very frustrating and unfulfilling. So I did temporary secretarial jobs, waitressing. Basically the problem with acting is for most people, even men, is that you end up unemployed for three quarters of the year and get the odd little job here and there. I never got any big sustained job in anything. I did a lot of television, I did commercials, but it wasn’t satisfying. And ironically one of the last parts I got before I gave it up was a big part in a Cold War thriller in which, get this, I paid a KGB officer. I was cast because I could speak Russian. It was rather funny and silly, but there was me stomping around in my KGB uniform and the big boots. It was a three-part miniseries.

After I did this, I thought it’s not going to get any better than this. I’m going to spend my life being out of work most of the time, being always broke. And when the work does come, it will be a few lines here and a few lines there. I really wanted to write history and get into publishing. Before I even gave up acting I’d started doing little bits of freelance history writing for publications, for instance for Reader’s Digest. After I gave up acting I managed to get editorial work at Blackpool Publishers in Oxford. I was living in Oxfordshire at the time. And from there I moved on into copy editing, desk editing. Eventually I was managing several books at a time as a supervising editor, and I was quite well paid, but I was yearning to write my own stuff. And eventually I edited a book by an Irish academic, it was a biography of Yeats. And we were sitting down, going through all my comments and questions about the text, and I remember very clearly, as he stopped and said to me ‘Helen, you should be writing your own stuff, not editing mine or anybody else’s’. And it was a matter of having the courage to give up quite a well-paid editing job and go completely freelance as a writer. And I was offered a book by a publisher in Oxford which was a branch of a big American reference publisher called ABC Clio. And it just so happened that I knew the managing director. And he said ‘We’re looking for someone to write a biographical companion to Stalin, are you interested?’ I thought oh my god Stalin… But actually I thought this is a challenge and it gets me a foot in the door. And so I did the biographical companion to Stalin and they came back and I did two more for them, one on Queen Victoria, and then a big two volume encyclopaedia on women’s social reformers. But I wasn’t earning enough, I was still having to fill in doing waitressing jobs and a bit of proofreading here and there. And eventually I was very fortunate, I did get my first book signed in 2006, and it was about a subject that I had embraced when I was 14 back at grammar school, which was the Crimean War. I did a book about women in the Crimean war, about the nurses. I did the Russian nurses, I covered the French nurses, the English nurses. In the course of researching that book I came upon Mary Seacole (Rappaport, Helen. In Search of Mary Seacole: The Making of a Cultural Icon, Simon and Schuster, 2022) but that’s another story. In fact I’d already found Mary Seacole but I engaged in a 20-year search and eventually wrote her biography. I got that book signed, and ever since 2006 it’s been a matter of holding your breath and hoping you sign the next book, and hoping you might get a few royalties or foreign rights deals, but I have been very lucky with my books on the Romanovs. I had a very very big success in America with Four sisters. In America, and this is a reference actually to my great love of Chekhov, when I decided to do the book on the four daughters of the Czar, I immediately thought of the title ‘Four sisters’ as an echo of Chekhov’s ‘Three sisters’. That was a deliberate echo of Chekhov on my part. Anyone who knows and loves Chekhov, especially in Britain, most well-educated people would have got that title, would have understood the illusion. The American market is different. The thing with the Americans, and it’s happened with every single book I’ve done, they come back and say ‘No you’ve got to call it the Romanov sisters’. The magic word in America for selling books in the history trade which is very difficult, very competitive is you’ve got to have a unique selling point. And my unique selling point after Capturing the Light (Roger Watson and Hellen Rappaport. Capturing the Light: A Story of Genius, Rivalry and the Birth of Photography. Picador, 2013), the first book I’d done, was Romanovs. They in the USA publishing industry said it’s got to have Romanovs in the title. So they called it the Romanov sisters, I called it Four sisters in the UK and some on the foreign rights, particularly Eastern European ones. I think the Poles and even the Dutch maybe, they called it Four Sisters in their translations rather than Romanov Sisters. So that was interesting. But for the American market, I have had a bit of a battle with every title of every book.

Well, I know that many emerging writers are afraid of the project of writing their own book. So maybe for those who think about a non-fiction book as their first book or for someone who just wants to have their book published, what are the steps? What is the routine without the romanticization of the process? What are the steps that you would recommend to take to publish your first book?

Honestly, I get asked all the time by people, friends, and readers, ‘I’ve written a novel, I’ve written a biography of my great-grandma, I’ve written this and that, how can I get it published?’ As if I’m gonna open the magic door for them and give them the secret of getting a book deal. I’m telling you now, it is 90% luck, 5% who you know and 5% sheer hard-plugging graft. Getting a publisher, if you’re a new author with a first book, I suspect now it’s unbelievably difficult. Getting your first book signed. The trouble is that the market has been so affected by the economic downturn and then COVID, and it shrunk and it shrunk, and a lot of what we call mid-list authors who are in the middle of the road, they’re not awful amateurs and they’re not brilliant bestsellers, they’re people who chug along and sell just at a steady stream, but a lot of mid-list authors especially in history have now been dropped, they can’t get their books signed. A very good friend of mine who’s with the same publisher as me in America, has had about three of her last book ideas all turned down. She’s a historian and she says I’m giving up now. I’m going to write fiction, because fiction is maybe a little bit easier to sell. My US publisher summed it up – the only books in America, and I don’t think it’s going to be much different in Britain, that now sell in non-fiction really really well are Romanovs, World War II and the Tudors, but maybe I think I’d squeeze in Queen Victoria.

We are talking about the process of actually writing a book. Let’s imagine you have a deal signed, what happens next, what are the stages of your work afterwards?

Well you’re not going to get anywhere selling a book without an agent, and this I’m afraid is the real stumbling block. Publishers have been so swamped with people sending in their manuscripts, what they call unsolicited manuscripts, i.e. I’ve written a novel, here it is, please read it and tell me you think it’s wonderful. They don’t look at them anymore. It used to be that every publisher would have one or two junior assistants who would sit and read through these piles, and they’re called the slush pile. The slush pile is the pile of manuscripts that haven’t been asked for, that people have sent, you know, they’ve written their life’s work, their granny’s autobiography, you name it. They send them in, and it is incredibly rare now for any manuscript sent in blind in that way to even get looked at. Because now if you send a manuscript for publication, it has to be channelled through an agent, because the agent’s job is to filter out stuff that’s hopeless or not good enough. So they will only look at manuscripts from an accredited agent, and to get an accredited agent you have to have a book published, so you’re in a catch-22. And why would an accredited agent with a lot of named authors on the list take on an unknown person with their first book? It’s very, very difficult. It maybe happens occasionally with new fiction, but getting a new book signed, getting an agent to sign you is incredibly hard. I mean, the same friend has tried endlessly to get a good agent, because she has one in the States, and she wants a British agent, and it’s just not happening for her. So because of this, a lot of authors now are bypassing the depressing fact that they can’t get agents or they can’t get publishers, and they are simply self-publishing. And I think print-on-demand, publishing online, is the only way now to go for new authors if they can’t get an agent. Because without an agent, it’s virtually impossible. So that’s the brutal truth. And I have to be brutal when people ask me. There’s no point in me saying, oh, yes, this is wonderful, you know, you’re going to get a publisher just like that. The chances are tiny.

But what does your actual work include? You can choose either a Petrograd book (Helen Rappaport. Caught in the Revolution: Petrograd 1917. Windmill Books, 2017) or a Lenin book (Helen Rappaport. Lenin in Exile. Making of a Revolutionary. Basic Books, 2010). Could you describe your process of work? How did you do your research? Did you go to different places in Russia for material for your books?

Yeah, that’s a big question. Each book has a different agenda and a different research plan. Well, let me just give you a few examples because it would take too long. When I did my first book, I did it for so little money. There was no way I could go to Crimea. That was impossible. But I knew the Crimea really well. I knew about the war. I’ve been reading about it since the age of 14. And I found pretty much all the material I needed in the UK, though I did make some very useful Russian contacts in Crimea. And I’m so grateful that I did two lecture cruises, one in 2011 and one in 2006 to the Black Sea, which took me to Crimea. So I have seen Crimea. I’ve been to the Livadia Palace. I’ve been to the wonderful Panorama Museum at Sevastopol. I’ve been to Yalta. I mean, I’m so glad I saw them… Anyway, the first book I did real on the ground research for was Ekaterinburg (Helen Rappaport. Ekaterinburg. The Last Days of the Romanovs. Windmill Books, 2009). Now, this was a really big leap in the dark for me, this book. First of all, I thought no one’s going to accept that title. But I wanted it to be about the place. It’s about Ekaterinburg, those last 14 days before they killed the Romanovs, from when Jurowski arrived to then when they killed them, took them out to the Koptyaki Forest. So I called it Ekaterinburg. And my English publisher accepted that title. In order to do that book, and I feel this very strongly with every book I write, I have to go to the place where it happened, or some of the places connected to the story to get a sense of place, to get a sense of the story I’m writing about. And I had never been further east than St. Petersburg. No, Moscow’s a bit further east, isn’t it? I’ve been to Moscow. So here I am. Just imagine this is me, a lone woman back in 2007 I’ve got to go there. And back in 2007, it was incredible, there actually was a direct flight, Heathrow, British Airways, to Ekaterinburg once a week on a Wednesday. Fantastic. So I got on this plane. Luckily, now before you travel with something like that, I mean, I was going into the Ural. To the Ural Mountains, beyond the Ural, to Western Siberia. To me, this is mind boggling. It was further than I’d ever been. So I made sure I made contacts before. So before I left, I got a couple of contacts in Ekaterinburg through people I knew at my old university, a couple of academics who volunteered to meet me and show me things. Wherever you go on a research trip, you have to set up a framework of contacts of people who know the place on the ground. I also found a wonderful Russian lady working for the British Council, and she was incredibly helpful. So there I am, arriving in Ekaterinburg. All that way on my own. I was quite proud of myself. But what was so wonderful, I met this lovely guy, Alex, he was an academic. And we walked all over Ekaterinburg, north to south, east to west. I found a local company who took me out by car to Koptyaki Forest, out to Ганина яма (‘Ganin’s pit’), and all the places connected with the story there. I was sorry I didn’t have time to go up to Perm. But I did at least go to the monastery of the holy Russian passion bearers out there. I went to the Novotihvinsky Monastery in Ekaterinburg, from where the nuns came bringing food, milk and eggs for the Romanovs. Of course, I walked up and down Voznesensky Prospekt, where the Ipatiev house had been, and went to the Church on the Blood. And I timed my visit to go when they had the Tsarsky Dni, The Tsar’s Days, in July. And I went to the all-night vigil. And I shall never forget that experience. The church was crammed and people were all on the grassy verges, all the way out from the church. And they had loudspeakers. This was before they had a screen. Later on now, they have a big screen. And I stood through that vigil and I spoke to the ‘babushki’. And I really, really got a sense of Russia that I could never have got had I not gone to Ekaterinburg. And that, all in that, and going out to Ganina Yama (Ganin’s pit) and seeing where the bodies were thrown, that gave me such a strong sense of the family and the atmosphere, which I hope I conveyed in the book. Because I don’t think you can write a story that has a powerful setting like that without going there. So, Ekaterinburg was very special.

But I’ll give you one other example because I can’t go through every book. When I did my book on Lenin in exile, this is Lenin from when he was released from jail in 1900 until he got on the train in Zürich to go back to the Finland rail station. And he lived in lots of places. He lived in London. He lived in Munich. He lived in Paris, in Poland. He lived in Zurich, in Finland. Finland was his favourite place because he could get there quickly up to Karelia, and hide out in a dacha somewhere in Finland. And the reason I particularly went to Finland, because it had the only surviving Lenin museum, it was at Tampere. I think it’s closed down. In fact, again, what I did, as I’ve said before, before you go anywhere that’s completely new to you and you don’t know the language, you have to make contacts. I thought I got to have a friendly Finn or two. I contacted the Lenin museum people, and they were fantastic and helpful. They met me off the plane at Tampere, they helped me find a good hotel. They took me, and this was really fantastic… When Lenin was fleeing Finland because the охрана was after him in 1907, he went down the southwest archipelago across the islands to hop on a boat and get to Sweden. I said to them, can I get a bus to go down there? I wanted to go across that huge sound, there was a big frozen sound of water that Lenin crossed on the ice and nearly fell in and drowned when he was escaping. And they took me there. They drove me all the way down the archipelago. It was fantastic. They took me up to Abu (Turku) where he was where he went when he first arrived, and I couldn’t have got that kind of context and comprehension of the story without going to Finland and being around real Finns. And the other thing I did on another different trip. Oh, no. On the same trip. I said, I would love to do that train ride down through Karelia into St. Petersburg. We went on the train from Helsinki. We did that train ride down past all the dachas and into St. Petersburg. And we went and looked at the big locomotive they had on the train that Lenin came with at the Finland railway station. She took my photos standing outside by the Lenin statue. You see, these are very special parts of researching a book. But you can only do that if they pay you enough money. With all my research trips, I haven’t had much money up front, and I had to self-fund.

And my last, my most recent trip I did with a friend – we drove down. This is very good friend of mine who drove me down to Coburg because I wanted to go to Saxe-Coburg to see the area where Juliane of Saxe-Coburg came from, i.e. Anna Fyodorovna. And from there we drove on down to Bern. And you see, again, this is where knowing someone who’s a specialist, is just so precious. I had found online and contacted a wonderful Swiss lady called Alessandra, who was a specialist on the Napoleonic period, on women’s dress. She was a curator at a nice country house outside Bern. She knew the period, and she knew Juliana. Because very few people, apart from me, knew anything about her story. And she, bless her, met me and my friend Nick, who drove me, and walked us all around this beautiful park called Elfenau, where there’s a house in the middle where Julie lived. And she took her to the places she went in Bern, and she arranged a special meeting for me with the archivist at the Bern Historical Museum, who took me down into the storage area at the museum and showed me books and china that had been Julie’s, but they were in storage, they weren’t on display. Now, you have to work hard to make those contacts. But they always pay off, and they enrich a book. With every book I’ve written, there are a huge number of people who help along the way. And plus languages that I don’t speak.

Do you read the previously done research both in Russian and in English? And do you use the sources both in Russian and English? Or do you do research in the British library?

Well, the British library isn’t the only place. In fact, I do very little research there. Most of my source material comes from archives all around the world. Particularly America. I get scans. The British library isn’t strong for Russian documentary material. Leeds Russian archive, my old university, is useful. They have a huge amount of Bunin stuff there. I do use Russian sources. But I have to say, and I’m going to be brutally honest with you. Until about the last few years, Russian sources were so poorly produced. No footnotes, or if they were, they weren’t… They were bad, they were inconsistent, they were faulty. No bibliographies, no indexes. Russian history books with no indexes become practically useless. Unless you can get an online edition and search online. I have also had huge problems with some Russian sources on Roma. And I’ve had a lot of problems with Romanos as being incredibly biassed and very much into conspiracy theories. I don’t go near that. But the best sources I used for After the Romanovs are documents, letters, diaries of people of the diaspora who left and who left a much more honest account. The problem is that after they murdered the Romanovs, you can’t find an honest word about the Romanovs, it was forbidden. And what was said, it was influenced by Soviet politics and it wasn’t worth reading. I never looked at anything written in the Soviet period. A lot of my material came from the foreign press – British and American magazines have a lot to say about the Romanov sisters, and also the memoirs of people who left were really valuable – they were to be found in the American archives. Speaking of Russian, I have now published four books in Russian. My publisher in Moscow is Eksmo. I am hoping they would want to buy Julie as this is a Russian subject as well.

When you did your two books on Petrograd and on the Romanovs, what is your view, why was this period so important, and what is the main backbone storyline of that period.

The reason I did Caught in the Revolution, which was about the foreigners who got stuck in revolutionary Petrograd, was that I’d been thinking that so much had been written about the Revolution and Bolshevism, and I suddenly thought that no one has really written a book from the another side of the revolution, i.e. the point of view of the foreigners who were there. And I had been collecting them, foreign eye witnesses, and there had been a huge number of Brits and Americans in Russia, particularly in Petrograd at the time, obviously for business, there were established British families who had factories in Petrograd, but also a lot of Brits and Americans and French were in the city at the time of the Revolution because they were Allies in the war effort. And there were also the wives and daughters of those businessmen, diplomats, soldiers. And when I started looking, I found an incredibly rich mine of fascinating descriptions of the experience of witnessing the Revolution in Petrograd that had hardly been touched. I had masses and masses of new eye witnesses, I have huge files still full of material. I decided I would focus on the British and the Americans, although there was also a wonderful Dutch diplomat who had written his memoirs. It was a wonderful joy writing that book, I never thought oh I didn’t have enough material. I had plenty. There is a book called Former people by Douglas Smith (Douglas Smith. Former People: The Destruction of the Russian Aristocracy. Pan, 2013) about the aristocrats who didn’t manage to get out of Soviet Russia, but I thought – what were the lives of those who managed to get out, what were their lives like. And I knew from what I had already read that the main focus of the diaspora of the early 1920s and 1930s was initially Berlin, but not for very long, and then Paris. And I thought I couldn’t write a book about the whole Russian diaspora, because people went to America, there was also an enclave of Brits in London. But to me the obvious place with good sources for the book was Paris – some lived there, some passed through before going to the USA as Nabokov, Chagall, Stravinsky. But what really fascinated me when doing that book was the number of women, a number of aristocrats well brought up were women, older and young women, arriving to Paris completely penniless, who found work in the fashion trade – for instance, Maria Pavlovna, the Great Duchess, who worked with Chanel. So that was of particular interest when I wrote the book. This book is available in Russian, and I have four books in Russian so far, my publisher in Moscow is Eksmo. I hope that they will want to buy my new book about Juliana of Saxe-Coburg, because that is also a Russia-related topic.