The British are famous for their love of tea, queues, and quirky humour. But dig a little into the past, and beneath the Victorian frills and strict protocols lies a far less cosy reality. We like to imagine history as a parade of stately banquets, knights, and tea ceremonies. Yet behind that façade were public executions for entertainment, dead infants in family albums, and dinners held in the company of the deceased. Pre-20th-century Britain knew how to shock. Today, we’ll take a walk through the country’s long-forgotten (and perhaps best forgotten) history, revisiting some of its eeriest customs.

Grim Britain: Traditions and Rituals of Death

Dead in the Armchair

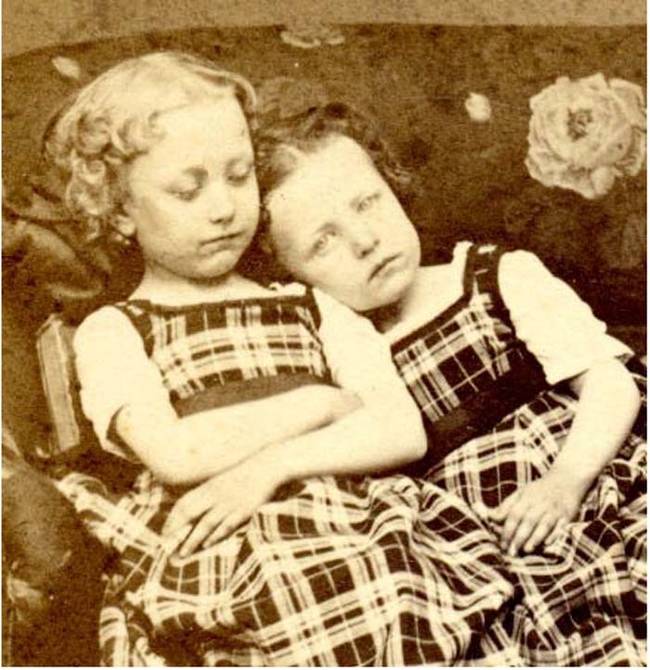

Photography existed in the 19th century but remained an expensive and rare luxury. Most families couldn’t afford a visit to a photo studio. But when a loved one died — especially a child — relatives seized the final chance to immortalise them, commissioning post-mortem portraits.

The deceased would be seated in an armchair or placed in a “natural” position, with efforts made to give the face a serene expression. To make the eyes appear open, they were either pried slightly ajar with pins or had pupils painted directly onto the eyelids. These images, known as post-mortem photography, belonged to the memento mori tradition (Latin for “remember you must die”). They became cherished family relics, treated with deep reverence.

Children were photographed especially often. They might be shown in a crib, a pram, surrounded by toys, or in the arms of their parents. Some of these photographs were so eerily lifelike that even today, historians and collectors can struggle to distinguish them from portraits taken in life. Back then, such images were not considered macabre but rather a means of coping with grief and preserving memory.

Public Autopsies

In 18th- and early 19th-century Britain, autopsies often became theatrical spectacles. Due to a chronic shortage of cadavers — especially after a surge in interest in medicine — dissections were typically performed on the bodies of executed criminals or the poor, who had no one to claim them.

Anatomical theatres in London, Edinburgh, and other university cities held public dissection sessions. Tickets were sold, and audiences — including students, doctors, and curious townsfolk — could watch the procedure. These events were often accompanied by lectures, and attendees were warned not to sit in the front rows: blood splatter and the stench of formaldehyde were very much part of the show.

The situation changed with the passing of the Anatomy Act of 1832, which allowed medical schools to legally use the bodies of paupers and prisoners, albeit under certain conditions. Although autopsies became more regulated, they still carried associations of poverty, marginalisation, and social powerlessness: the bodies of the poor could be dissected without prior consent, simply because no one came to claim them.

Picnics on Graves

Another long-forgotten practice was holding picnics… in cemeteries. In Victorian Britain, this wasn’t just acceptable — it was fashionable. Families would visit the graves of loved ones with sandwiches and tea, lay out a blanket among the tombstones, and spend the day reminiscing, reading letters, chatting, and even playing board games.

This tradition was especially popular in park-like cemeteries such as London’s Highgate, which were designed as “gardens of memory” — public spaces meant for reflection and rest. Some families held full-scale feasts with music and brought their children along, believing it was important to teach them about the transience of life and the naturalness of death from an early age. Though there’s a touching sincerity to it, the modern mind may find the idea of eating cake beside a gravestone quite unsettling.

In rural Britain and Ireland, there was an even more unusual mourning ritual: feasts held immediately after autopsies. Sometimes the body was brought home from the morgue and laid out in one room while a table was set in another. Such customs highlighted how closely death was woven into daily life. Proximity to the dead was not feared — it was seen as normal. These practices gradually faded with the rise of medical infrastructure, the introduction of public health standards, and the establishment of hospital morgues in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Amulets from Executions

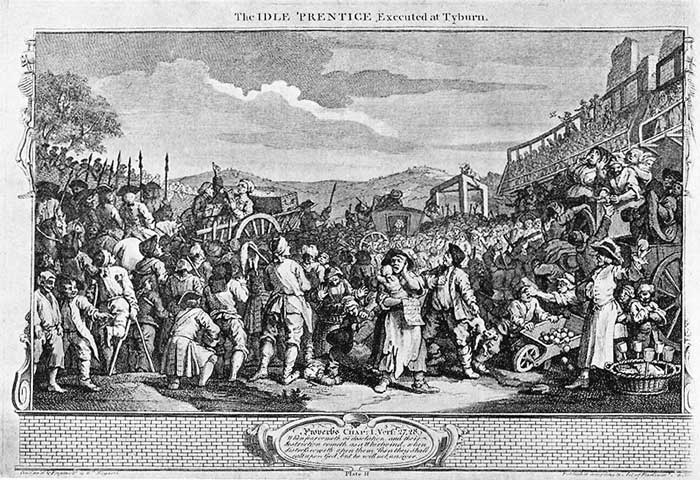

Until the early 19th century, one of Britain’s most sinister and superstitious customs persisted: the belief in the magical power of execution relics. Executioners, especially in major cities like London and York, often sold pieces of the rope used in hangings. These fragments were thought to be powerful amulets, particularly among the poor and street traders, believed to ward off illness, misfortune, and even bring luck in business.

The executioner’s status went even further: it was believed that his touch had healing powers. People thought that being touched by an executioner’s hand could cure epilepsy (then known as the “sacred disease”), skin conditions, ulcers, and warts. Historical records describe cases where parents brought their sick children to Tyburn (London’s execution site), pleading with the executioner to touch them with his “killing hand.”

These “healing sessions” eventually died out as scientific medicine developed and public perception of executions shifted — they came to be seen as legal procedures, not mystical rituals. Nevertheless, historians note that executioners were feared, reviled, and secretly revered all at once — they stood at the boundary between the living and the dead, law and crime, fear and healing.

Today, death is hidden behind hospital walls and crematorium curtains, and discussions about it are shrouded in discomfort. But just two centuries ago, the line between the living and the dead in Britain was much thinner — almost transparent. The deceased were propped in armchairs, photographed, dined beside, and touched for healing. Executioners were viewed as part hangman, part sorcerer. These strange and sometimes disturbing customs were not anomalies — they were part of daily life, a way to cope with loss, confront fear, and integrate death into the living world.