Iya Patarkatsishvili: “There’s no inspiration in this – only a cry from the pit of despair”

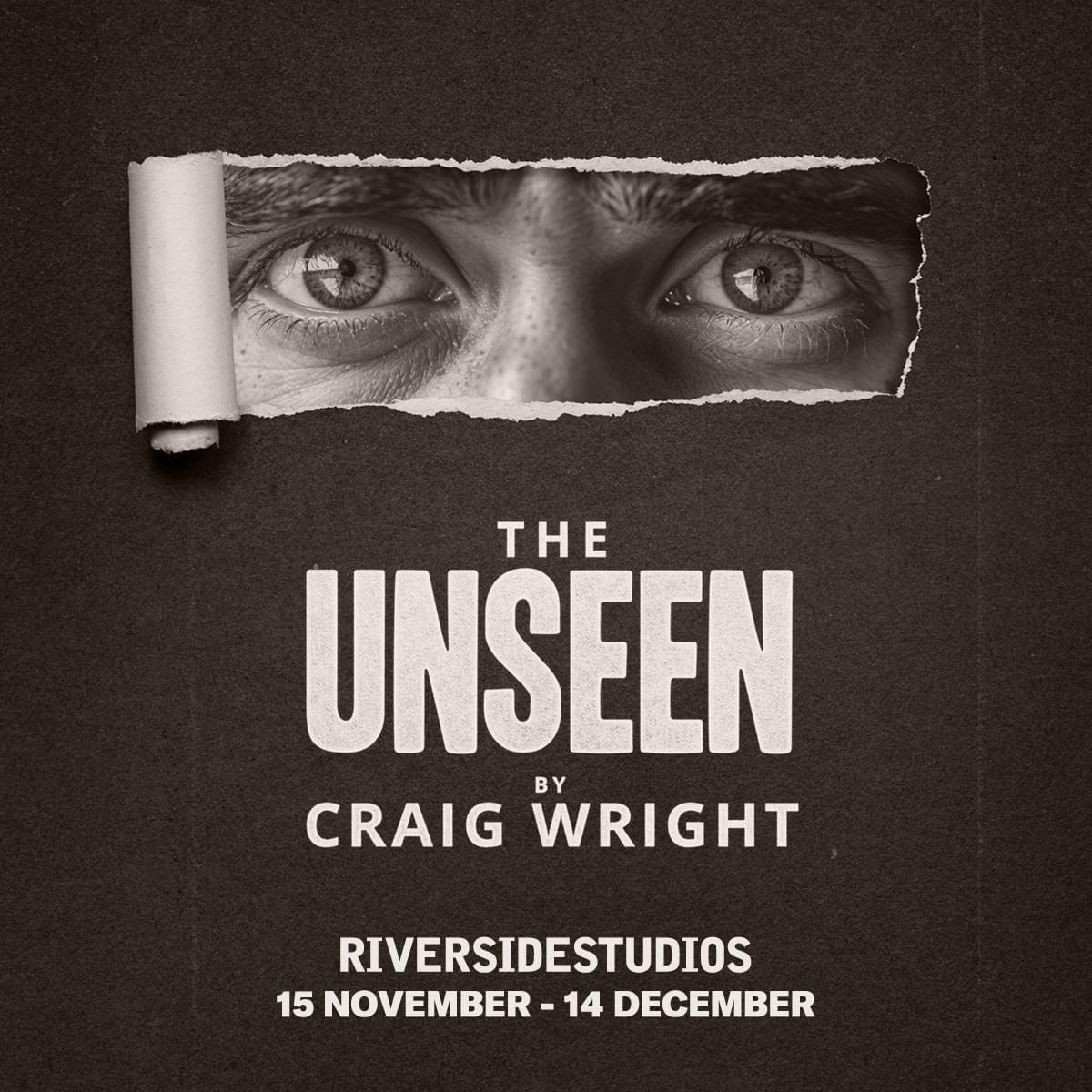

Iya Patarkatsishvili is a political activist advocating for human rights, with a particular focus on Russian political prisoners. Leveraging her extensive knowledge of the arts and her personal experience in politics, she uses the theatre as a platform to explore the nuances of human nature. For Patarkatsishvili, theatre is a powerful tool for conveying passionate activism. Her directorial debut, The Unseen, a thought-provoking drama by Craig Wright, premieres at Riverside Studios this fall.

Iya Patarkatsishvili is a political activist advocating for human rights, with a particular focus on Russian political prisoners. Leveraging her extensive knowledge of the arts and her personal experience in politics, she uses the theatre as a platform to explore the nuances of human nature. For Patarkatsishvili, theatre is a powerful tool for conveying passionate activism. Her directorial debut, The Unseen, a thought-provoking drama by Craig Wright, premieres at Riverside Studios this fall.

– Did you collaborate with Craig Wright on the play? Did you communicate with the playwright?

– I applied for the licence to stage the play in London. Craig reached out to me, and I explained my intent to draw parallels to the lawlessness happening in Russia. In its essence, this is a parable and universal story. However, it’s important to me to convey the truth about modern Russian gulags. So, we made a mutual decision to adapt the play. It’s now quite different from the original version, but I believe it has gained much more depth.

– How did the casting process go? Was there an open call for roles?

– It was a standard process organised with the help of a casting director. She selected a number of actors, and auditions were held.

– The play doesn’t directly mention any specific country? Is it about a totalitarian society, without being tied to a particular name?

– Yes, it depicts a totalitarian regime that, unfortunately, resonates beyond just Russian-speaking audiences. But my goal was to specifically portray Russia after the war in Ukraine started and how it affected those who dared to speak out. While it remains a parable, for Russian-speaking viewers, there is a direct reference to Russia.

– As a director, where do you find the strength to speak on such heavy subjects from the stage?

– I think it’s less about having strength and more about feeling powerless, angry, and desperate. There’s no inspiration in it – just a desire to scream, not into the void, but with a hope that more people will learn about this and be able to help.

– What is guilt? Can it be separated from responsibility?

– I believe that a responsible person inevitably feels guilt. An honest and conscientious person feels shame or discomfort – all forms of guilt for perhaps not doing more. So, this distinction is in the eye of the beholder.

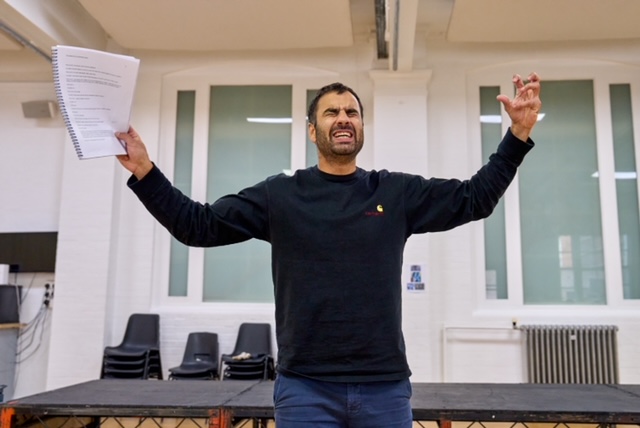

– How has the work on the play been going? What did you tell the actors, how did you define their roles? Did the story initially feel distant from reality to them?

– We’re still in rehearsals, but in the first two weeks, we analyzed this philosophical play line by line. I also provided the actors with a lot of information on Russian political prisoners, including documentaries about Navalny, various articles and interviews, and references to Orwell’s 1984, Umberto Eco, Natan Sharansky, Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones, and more.

– There’s a photo exhibition in the lobby. Who is the photographer? How did you select the photos for it?

– Faces of Russian Resistance is a series of exhibitions across different cities worldwide, focusing on Russians who stood up against Putin’s criminal regime and paid for it with their freedom. The project was conceived and organised by Elena Filina, a municipal councillor from Moscow’s Vernadsky Avenue district, who is currently wanted internationally. This wonderful volunteer-based initiative brings these crucial stories to light.

– Is the exhibition a prelude to the play? Do you aim for the audience to enter a state you, as the director, want them to be in by surrounding them with these documentary images?

– My idea was to debunk the myth that a political prisoner is necessarily a Nelson Mandela, who was himself a controversial figure at the beginning of his political career. It’s also not always someone willing to die for an idea – figures like Alexei Navalny are rare. I wanted to show the British audience that the regime’s most dangerous enemies turned out to be people of all professions who simply dared to voice their opinion. Or they called the war a war. Or opposed violence and the killing of innocent people in a neighbouring country. Orwell wrote it all. War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength.

So, when someone buys a ticket to the play, they immediately see the exhibition and learn the stories of real people, “guilty” only of their courage and integrity. Additionally, from November 28 to December 12, there will be a series of post-performance talks by Dmitry Muratov, Vladimir Ashurkov, Elena Kostyuchenko, and Sergei Davidis, as well as Q&A sessions.

– The Unseen is a literary, artistic work. How do you view the documentary theatre genre?

– I can’t claim to have seen a lot, but I wouldn’t consider verbatim theatre a separate genre. It’s more a way of presenting material, a form that, like any other, has a right to exist in theatre.

– Are political activism and theatre compatible? Can we say something through art that we cannot express in other ways?

– Yes, they are quite compatible, but only when it doesn’t turn into propaganda, otherwise, it’s mere manipulation. With The Unseen, I pursue several goals. First, to draw attention to the issue of political prisoners in Russia through art. The second goal is to invite reflection on human nature, urging people not to close their eyes to uncomfortable truths about ourselves. The more we speak of our darker qualities, the more hope there is for growing humanity.

Additionally, it’s a philosophical narrative that explores themes of not just the necessity but also the danger of hope, guilt, the desire to look away and be “non-political,” learned helplessness, and the cost of survival under such inhumane conditions.

– Is the play an opportunity for self-reflection for you? Or is it a way to communicate your position and feelings to the audience, helping them feel what you feel?

– It’s an invitation to discuss topics that may be uncomfortable but are nonetheless vital. I try to avoid moralising, so for me, theatre is a platform for open discussion where all sides are ready to change their perspective if presented with convincing arguments.

– Do you imagine your audience?

– Yes, it’s anyone willing to delve into the complexities of human nature and isn’t afraid to find something unpleasant there.

– Do you often go to the theatre in London? What has been a notable event for you?

– Not as often as I’d like. But I can’t say I rush to every new production, nor would I consider myself a theatre connoisseur. Recently, I found The Slave Play quite amusing, was aesthetically thrilled by Macbeth with David Tennant and the incredible Cush Jumbo, and the play that forever won my heart is Pillowman at Duke of York.

The performance will run from November 15/ 2024 to December 14/ 2024.