“Bigger, louder, bolder, stranger” — if Leigh Bowery had left us a will, it might have sounded something like this. Tate Modern’s new exhibition, Leigh Bowery! — yes, with an exclamation mark, because anything else wouldn’t do — reveals the full scale of Bowery’s talent and courage. His name, once whispered in the smoky depths of London’s 1980s club scene, now shines on the walls of one of the world’s most prestigious museums. But has Tate done justice to Bowery’s legacy? In short: absolutely.

Leigh Bowery at Tate Modern: The Rebel Triumph of Flesh

A self-proclaimed “living artwork,” Bowery never confined himself to a single medium. He distorted, wrapped, and inflated his own body, transforming it into a living sculpture that defied traditional notions of beauty, gender, and taste. For the first time, the exhibition brings together not just Bowery’s dazzling costumes but the full spectrum of his creative legacy — club culture, performance, fashion — finally securing his rightful place in the pantheon of contemporary art.

From Sunshine to Soho: The Birth of a Legend

The exhibition doesn’t open with the neon frenzy of London’s nightlife but with the pastel stillness of Sunshine, Australia, where Bowery was born in 1961. His early life is explored through photographs depicting an awkward boy yearning for transformation, setting the stage for the explosion to come.

When Bowery arrived in London in 1980, Thatcherism was in full swing, conservatism was stifling self-expression, and society was in desperate need of a shake-up. Bowery delivered.

He found his calling in London’s underground club scene, where excess wasn’t just encouraged—it was mandatory. His era at Taboo, the nightclub he founded in 1985, takes center stage in the exhibition’s second section. Photographs by David Swindells and Derek Ridgers capture Bowery in his natural habitat: a neon deity ruling over a world of unbridled creativity. His parties became spaces of “anti-productivity,” a rebellion against the workaholic ideology of the time—living art installations where every outfit was a manifesto, every movement a political statement.

Punk Ballet and the Art of Pain

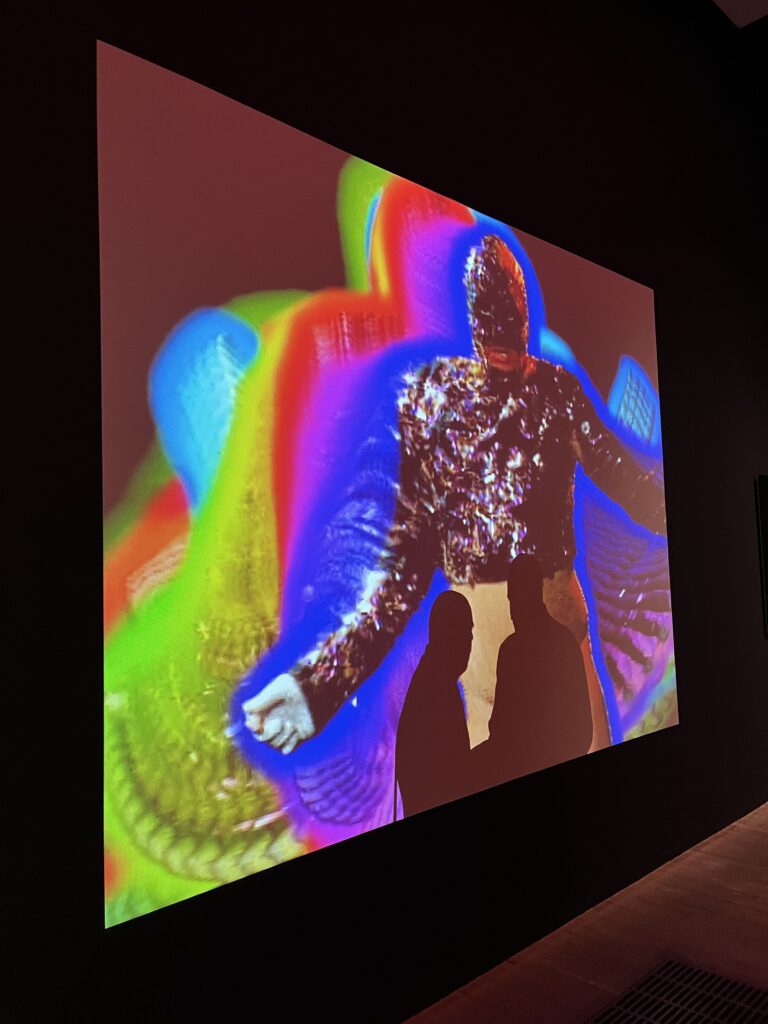

Bowery’s transition from the club scene to high art is traced through his collaboration with punk dancer Michael Clark. Excerpts from the films Hail the New Puritan (1986) and Because We Must (1989) pulse with the energy of their partnership — Bowery’s grotesquely exaggerated costumes transforming dancers into hyper-sexualised, absurdly distorted mutants. These works remain strikingly modern, anticipating today’s conversations on body politics and performativity.

And then — discomfort. Leigh Bowery’s art was never easy or convenient. He strapped his body into excruciating corsets, expanded it with prosthetics, and wore latex masks that turned his face into something alien. Pain, for Bowery, was a tool — a way to reclaim his body from society and the state. He stretched skin, exaggerated flesh, became other, challenging norms of identity and desire. It’s impossible to watch his infamous performance, where he theatrically “gave birth” to his friend Nicola Bateman on stage, without drawing parallels to contemporary discussions on gender.

From Gallery to Canvas: Bowery and Freud

Perhaps the exhibition’s most unexpected and intimate section explores Bowery’s relationship with Lucian Freud. The great painter of flesh, known for his unflinchingly raw depictions of the human form, found in Bowery an ideal muse. Unlike Freud’s typically passive sitters, Bowery was an active participant in his own myth-making — rumour has it that when Freud wasn’t looking, Bowery would add a few brushstrokes to his own portraits.

The works displayed in the exhibition reveal a different side of Bowery: open, contemplative, utterly at ease in his monumental physicality. He once declared, “Flesh is the most fantastic fabric,” and in Freud’s paintings, that truth is laid bare.

Minty, McQueen, and the Final Performance

Bowery’s final act, in every sense, was Minty — a band that fused grotesque spectacle, cabaret, and shock art. A brilliantly executed multimedia installation by Jeffrey Hinton recreates the atmosphere of Minty’s performances: a cacophony of fetish latex, distorted pop, and transgressive humour. The show’s climax? Footage from Bowery’s last-ever performance at London’s Freedom Café in 1994. Among the audience that night were Lucian Freud and a young Alexander McQueen — proof of Bowery’s far-reaching influence.

Just weeks later, Bowery was gone. His death from AIDS-related complications at just 33 was a devastating loss to art, fashion, and the queer community.

A Legacy Without Limits

Yet this exhibition isn’t a conventional retrospective. It’s a celebration — a joyous, anarchic, unrestrained tribute to a man who refused to be confined by anything. Leigh Bowery didn’t just challenge boundaries — he obliterated them.

One thing becomes clear: Bowery foresaw the future. In today’s world, obsessed with digital identities, self-reinvention, and the dismantling of binary norms, his legacy feels more relevant than ever. Tate Modern honours his genius, inviting us to see the world through Bowery’s eyes — a man who proved that you can be art.

The exhibition runs from February 27 to August 31, 2025.