Leprosariums of Medieval Britain: Fear, Mercy, and the First Healthcare System

Leprosy was one of the most mysterious and frightening diseases of the Middle Ages. In Britain, its outbreak peaked in the 11th–12th centuries, leading to the establishment of hospitals for lepers across the country. These early leprosariums were not just medical institutions but also important social structures reflecting the anxieties, beliefs, and moral values of medieval society. They stood at the boundary between humanity and isolation, care and estrangement. Many of these institutions have not survived, but some can still be seen today.

The Emergence of Hospitals for Lepers

Leprosy reached England by the 4th century and had become an integral part of life by 1050. Society’s response to the disease was mixed — some viewed it as divine punishment for sins, while others believed that the suffering of lepers mirrored the experience of purgatory, making them spiritually closer to God and ensuring them a place in heaven. Those who cared for lepers or donated money to them hoped that such acts of charity would shorten their own time in purgatory — in other words, that they would be “credited” for their good deeds.

The earliest known leprosarium in England was St. Mary Magdalene Hospital in Winchester, Hampshire, where excavations have uncovered burials dating from 960–1030 AD. It housed lepers who were provided with food and shelter in exchange for adhering to strict monastic rules. Despite their isolation, residents received medical care and could participate in religious life through specially designed rooms with windows allowing them to observe church services.

By the 12th century, medieval England had developed a network of at least 320 leper hospitals. These institutions were often built on the outskirts of towns or near major roads, allowing lepers to maintain some contact with society. Many engaged in begging, small-scale trading, and praying for the souls of others in exchange for donations.

St. Giles’ Leprosarium in Essex

Founded in the 12th century, St. Giles’ Leprosarium served as a final refuge for lepers in southeastern England. Residents were required to keep their distance from healthy individuals and were obligated to wear bells to announce their approach. As leprosy cases declined in the 13th–14th centuries, St. Giles’ was repurposed as a shelter for the elderly and disabled, and later, it was even used as a barn.

Despite their condition, lepers in such hospitals led relatively stable lives. Hygiene was emphasised — clothes were washed twice a week. Gardening was considered therapeutic, and many hospitals maintained gardens with medicinal herbs and flowers. Leprosy did not lead to a complete severance of social ties; many lepers maintained contact with their families, received visitors, and were even permitted to return home for short periods.

A Leper Island Off the Coast of Scotland

Brei Holm, a tiny landmass near the Scottish Isles, was long believed to have been a place where lepers were exiled until the 18th century. Connected to the mainland by a narrow strip of land visible only at low tide, Brei Holm seemed almost purpose-built for isolation. However, some researchers suggest that those labeled as lepers on the island may have actually suffered from severe vitamin deficiency, which can cause similar skin and limb damage.

Ruins of several rectangular structures, known as “leper houses,” still remain on the island, reinforcing its grim reputation. However, recent archaeological findings cast doubt on this history — excavations suggest that Brei Holm was originally a monastic settlement (with buildings of Norse origin dating back to the 5th–7th centuries) before later being repurposed as a refuge for the sick.

St. Mary Magdalene’s Leper Chapel in Cambridge

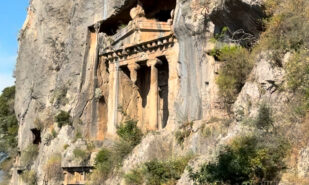

One of the oldest surviving chapels in England, St. Mary Magdalene’s was built around 1125 adjacent to a leper hospital, located along a road leading out of medieval Cambridge. Constructed in the Romanesque style, the chapel provided a place of worship for the sick.

By the late Middle Ages, the hospital had been disbanded, and the chapel found new purposes — first as a resting place for pilgrims and later as the center of an annual fair, which became the largest in medieval Europe. In fact, the prosperity of this event was so great that the post of priest at this small chapel was considered one of the most lucrative in the country, while the fair itself became the inspiration for the term “Vanity Fair”. Despite its modest size, the chapel has survived for over nine centuries, experiencing both periods of prominence and neglect, and today, it stands as the oldest preserved building in Cambridge.

The Historical Legacy of Isolation

By the 14th century, attitudes toward leprosy had shifted, particularly following the Black Death. Heightened fears of contagious diseases led to stricter isolation policies and, in some cases, harsher treatment of lepers. However, the disease itself began to decline, possibly due to increased immunity among the population.

Many remaining leprosariums fell into disrepair during the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII in the 1530s. Nevertheless, some have survived, including St. Nicholas’ Harbledown Hospital in Canterbury (established in the 11th century), St. Mary and St. Margaret’s Hospital in Norfolk, and St. Mary’s Hospital in suburban London.

Leprosy left behind an important legacy. Institutions for lepers laid the foundation for disability care and social welfare. The surviving ruins of leprosariums serve as a reminder of a past in which isolation was the primary method of combating epidemics. Today, they stand as historical landmarks, illustrating how far medical and epidemiological attitudes have evolved.