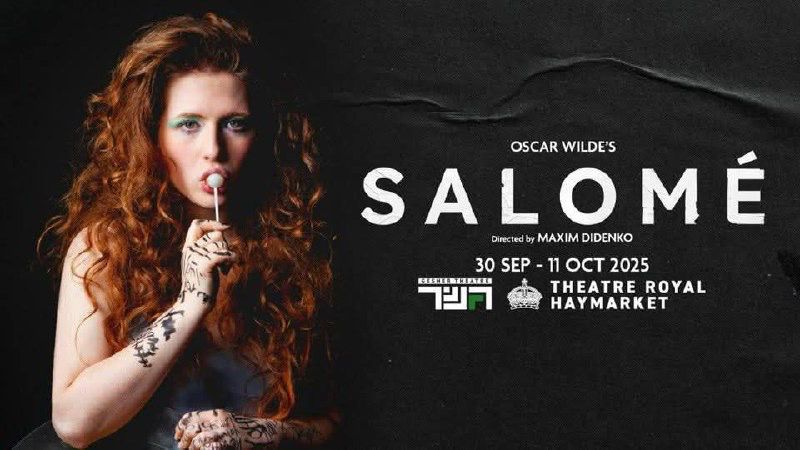

Maxim Didenko and Galya Solodovnikova: «Salome» in London

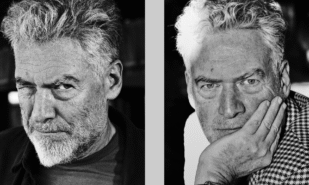

In London, two artists who have long worked together and deeply understand each other — director Maxim Didenko and scenographer Galya Solodovnikova — reunite on stage. Their new Salome, brought from Tel Aviv’s Gesher Theatre to the Royal Haymarket, transforms Oscar Wilde’s classic play into a pressing conversation about power, desire, and the brutality of the modern world. We spoke with Didenko and Solodovnikova about creating the production during wartime, why it had to change languages and casts along the way, and how artistic choices strike a balance between beauty and concept.

Maxim, how did it all begin?

I staged this production at the Gesher Theatre a year ago, during the war—but rehearsals had started much earlier. At first, we wanted to stage Salome in Hebrew. But when Lena Kreidlina, the theatre’s director, told the ticket sellers about the plan, the elderly Israeli women working there asked her what play it was and who Salome was.

Really? They didn’t know?!

Can you imagine? The story wasn’t at all popular in the land where it actually took place. Lena explained the plot, and they were horrified, saying: “We don’t need this. We won’t sell the tickets!” At that moment, I was sitting on the beach, confident everything was fine—we’d already cast the show, everything was in place. Then Lena calls me: “Maxim, we’re not doing it in Hebrew. Russian-speaking Jews are more liberal, let’s stage it in Russian.”

So, we had to start a new casting process—Hebrew-speaking actors usually don’t perform in Russian. We assembled a Russian-speaking cast. But then, just a week before rehearsals, on October 7, the war began. Our readings had to take place online: the actors were sitting at home in bomb shelters. Sometimes the air raid sirens would cut off the connection.

And then another question came up—who would need Salome in Russian? That’s when the collaboration with the Royal Haymarket appeared, so we staged the play in English—with a third cast. There aren’t many actors capable of handling such a complex text in English. Three roles are especially demanding: Salome’s monologues are huge, Herod speaks endlessly, and of course John the Baptist. Bringing such lofty texts to life in English, when you’re not a native speaker, is no easy task. But we found three astonishing actors—Neta Rot, Shir Sayag, and Doron Tavori. You can imagine how many times the concept, the language, and the cast changed, and how many perspectives I gained on this play.

When did rehearsals begin?

In May last year. The war was at its peak, but that didn’t stop me and my team from spending seven incredible weeks in Tel Aviv, staging this play on the very land where this ancient story unfolded. Visiting Jerusalem was unforgettable. We stayed in a huge, old hotel on the Mount of Olives—built by Americans in the 1960s, originally meant to reconcile Palestine and Israel. A giant conference hall, 600 rooms, luxury everywhere—yet the building stood completely empty on top of the hill, where no religious structures are allowed. Around it: fences, gates, mosques. At night, the muezzins were chanting, and the slope of the mountain was covered with the graves of ancient Jews awaiting the Messiah.

And at the foot of the mountain—the Old City, eerily empty at the time. The Holy Sepulchre stood deserted. The war and this centuries-old conflict created a phantasmagoric atmosphere.

Did this journey influence the production?

Very much so. This is the story of a king who killed his brother to seize the throne, then married his brother’s widow, and lusted after his stepdaughter. It’s a suffocating, archaic world—a toxic mix of hunger for power, endless conflict, and a harsh ancient way of life.

It’s the kind of world where someone could easily slit your throat and leave a corpse in your yard, while at the same time you’d see the envoy of Caesar—or, today, perhaps the US ambassador—sitting nearby.

What I saw felt like our reality. Here it is: people can break into a house, burn children alive, and in the same place host ambassadors. And this is still happening on that land today.

It didn’t inspire me—it horrified me. It tore open a tunnel through time, showing me there’s no difference between those ancient days, Wilde’s time, and our present. For the people I worked with—born on that land, speaking that language, breathing that air—Wilde’s text is strikingly relevant, alive, without pretension or artificiality. That level of passion is their daily reality.

Before rehearsals for Salome in May 2024, I had been in Dresden staging Kafka’s The Castle. The Germans are calm, meticulous—you can’t move forward until you’ve analyzed every line. Immediately after that, I came to Gesher and said: “Let’s run through the whole play!” And, to their credit, the actors at Gesher performed with talent, abandon, and courage. It was so powerful that many elements from that first run-through made it into the final version.

How many rehearsals did you have at the Royal Haymarket before the premiere?

On Monday we rehearsed all day, on Tuesday we had a morning run, and in the evening we performed. That’s how it works here. I had rehearsed Salome for a long time in May 2025, then was supposed to fly to Bonn to work on Giya Kancheli’s opera Music for the Living. But I couldn’t leave—someone fired a rocket at Ben Gurion Airport, it broke through the Iron Dome for the first time, landed near the airport, and left a crater twenty meters wide. All flights were canceled except for Russian, Georgian, and Israeli airlines. I had German tickets, so I was stuck and missed a couple of rehearsals in Bonn. Ironically, Music for the Living begins with a rocket hitting a theater. I thought, maybe that rocket flew straight out of my opera. Luckily, no one was hurt.

My teacher and friend Anton Adasinsky told me: “Maxim, get into that crater—rockets never hit the same spot twice.”That’s the kind of humor surrounding us these days.

You’ve mentioned having a long history with Wilde’s play…

I first studied in Omsk under Moisey Vasiliadi, an actor at the Omsk Drama Theatre, then moved to St. Petersburg. My master there, director Grigory Kozlov, had staged Salome in Omsk with Vasiliadi playing Herod. I never saw the production, but they spoke endlessly about it. So Wilde’s text carried this added magic of my earliest theatrical impressions, through my teachers.

Why the 1920s aesthetic?

I wouldn’t say we leaned heavily on it. I told the set designer, Galya Solodovnikova, that it was the palace of a dictator in a small Middle Eastern country today. She chose Art Deco, something like a luxurious hotel lobby where a reception takes place—or the palace of an oligarch-dictator. It’s more a reference to Art Deco in a modernized form. We tried to span the period from mid-20th century to today—basically since the founding of Israel. We aimed for the most contemporary resonance possible: the dictator, the hostage locked in his basement… It turned out to be all too relevant, honestly. And we conceived this concept even before October 7.

You’ve worked in London before. Do you find the audience here different from elsewhere?

Absolutely. It’s a unique, multilayered audience. There’s a significant Russian-speaking community, a large Jewish diaspora, and, of course, the core English theatergoers. Ingeborga Dapkunaite told me about the Lithuanian audiences who come to her shows—it’s not the same group of people. I’d say London audiences are just as diverse. And then there’s the specific West End audience. London is unquestionably a theatre capital—similar to Moscow in that sense—but what sets it apart is its multicultural, layered society. A pie of communities. You’ll never get bored here.

Which of your projects has stayed with you the most?

Without a doubt, The White Factory. We worked on it for six years, won many awards with it. It was my first project with a large group of English actors, an English production team, and in the English language.

And how does an English production differ from a Russian one?

Radically! Everything is different—it’s a completely different structure. I was shocked for the first three weeks, I couldn’t understand who was responsible for what, or how things worked. You can’t speak to the actors directly—you have a manager, you talk to them, and they relay it to the actors. If you try to address actors directly, nothing happens.

During previews, I rehearsed for ten days straight—giving notes to actors, and they just walked away. I yelled at them, and they looked at me like I was crazy. Then the producer told me: “Look, if the stage manager signals with a flashlight, then they respond.” And that’s how it works across every level of production. It’s another philosophy, another rhythm of life, everything is different. For a Russian actor to adapt, they need to completely reset their rhythm of breathing, their tempo of thinking. It’s even a bit easier for a director, since we don’t have to perform eight shows a week. But for actors—that’s their reality.

Galya, this isn’t your first production with Maxim Didenko.

I’ve lost count already — definitely more than ten.

With each director you need to find a different language of communication?

Of course. Each collaboration is unique — there’s no single recipe. Every time you need a delicate fine-tuning, to understand how another person thinks, how they process information. Some people are visual, some are logical — images say nothing to them. With Maxim, visuals are essential, images are his way of thinking.

This tuning takes time. The first production with a new director is always difficult. But once you’ve gone through fire together, you start understanding each other at half a word.

I’m a team player. I work to make the production succeed, not to “express myself” at its expense. That stage I’ve passed. At the beginning of your career, you want everything to be brilliant, you try to pack all you know and can do into a show. Later you realize: you need to work with one clear method. The main thing is not your work but the success of the performance. Sometimes that means sacrificing personal ambitions. Maybe you want it “beautiful,” but the director needs it raw, ugly, even trashy. A choice may go against my taste, but if it works for the show — that’s what matters.

You transferred Salome from the Gesher Theatre stage to the Royal Haymarket. These are very different spaces. How did the set adapt?

I never design a show without knowing the venue. It’s crucial. I need to know the proportions of the stage, its spirit, atmosphere, where the audience sits, from what angles they watch.

With Salome, I was amazed at how perfectly the set fit. From the start, we built it for both venues, checking proportions with 3D models. The Gesher stage is a wide rectangle; the Royal Haymarket is deep, vertical, with a raked floor. But everything settled as if it belonged there. It even looked like a continuation of the gilded auditorium — the aged gold of this royal theatre flowed seamlessly onto the stage. I was absolutely happy. And of course, it wasn’t luck but the result of long technical calculations.

The production had three casts. Did you adjust the costumes depending on the actors?

Absolutely. We searched anew each time. Actors looked different, their characters were different. For example, Herod: Anatoly Bely is one thing, Doron Tavori completely another. Different presence, different energy. And Salome too — we redesigned her costumes because the actresses had entirely different natures.

When you first read a play, do you already see the images that later appear on stage?

The first reading is free and intuitive. The second, though, is aimed at the result, once visual images and concepts appear. The second reading tests the new concept.

You had a fashion brand, ALOE, yet you are primarily a stage designer. Is there a difference between costume for theatre and everyday fashion?

Enormous. It’s a completely different approach. Fashion design has other goals: it develops visual language within the context of contemporary culture. Fashion reflects our view of society itself. You have to catch fleeting waves that arise in a constantly changing context.

Theatre exists in all times at once. You can stage Ancient Greece, you can stage the Baroque. And you must consider both text and context: what ideas, what archetypes, what characters live in this world you’re creating? Fashion also supports personalities, identities, often linked to status or subculture.

Theatre costume, though, must both reveal the character and reflect the meaning of the world on stage — a world that can be entirely different from reality. It may follow completely different rules. Each time we reinvent reality.

How do you see modern technology, including AI?

My view is simple: you can’t fight it. It develops whether we want it or not. So the question is how to use it creatively. Alongside apocalyptic scenarios, there are benefits these tools bring. I’m not afraid at all. For me, AI is a fantastic research tool. I use it to shift perspective. In the past, if I needed to study, say, Mongolian costume, it would take weeks. Now I can gather it instantly, and then navigate from there. I never take AI’s output at face value — it’s just a tool. But its speed and scale break your usual perception patterns, opening new directions.

Right now, in Potsdam, I’m working with German director Andreas Merz on Dürrenmatt’s The Physicists, staged as a piece about artificial intelligence. With Andreas, I previously did Three Sisters from Moscow in Augsburg, based on the Khachaturyan sisters’ court case, even using transcripts of their testimonies. It became a powerful play against domestic violence — a painful subject in Russia, especially now.

The Physicists, however, is very different: absurd, very funny. Dürrenmatt originally asked: can a scientist release an invention if society might use it against itself? Today the theatre says: let’s talk about AI — as significant as the atom bomb.

We’re using huge amounts of AI-generated content: text, music, video. I work with AI’s mistakes, too — those errors are fascinating.

You also teach. What does teaching mean for you as an artist? A way to share experience?

I still teach at the British Higher School of Design. With Polina Bakhtina, we’ve been curating the course for eleven years. It’s a year-long program, almost like a Master’s, for people who already have higher education and want an upgrade. For me it’s very valuable: I’ve grown a lot thanks to teaching. It keeps me connected with creative youth from Russia, which is vital for me. Through their projects, I see what’s happening with them, and with society.

We do about eight projects a year in different genres. Every year we pick new texts — always those that interest us too. It becomes a joint lab where we test new possibilities. If there are fifteen students, we develop fifteen different solutions. That’s inspiring.

Once, for a graduation project, students created their own manifestos: they imagined a utopian theatre and staged Hamletin that genre. The projects were incredible — and the most amazing thing is that two years later, many of them had implemented their manifestos in real life. That is deeply inspiring.

A broad question: what does beauty mean to you?

It’s too abstract. In people, beauty always comes from the soul. In theatre, though, beauty became a disqualified word at some point. It was replaced by “concept.” Art is not there simply to please the eye; it must provoke feelings, ask questions, make the viewer work. I had to fight myself here, because I do love things to be stylish, neat, beautiful. But that’s my evolution — from designer to artist. Sometimes you must step on the throat of your inner designer.