Serious Jokes; Alexander Panchin Tells London About Genetic Engineering

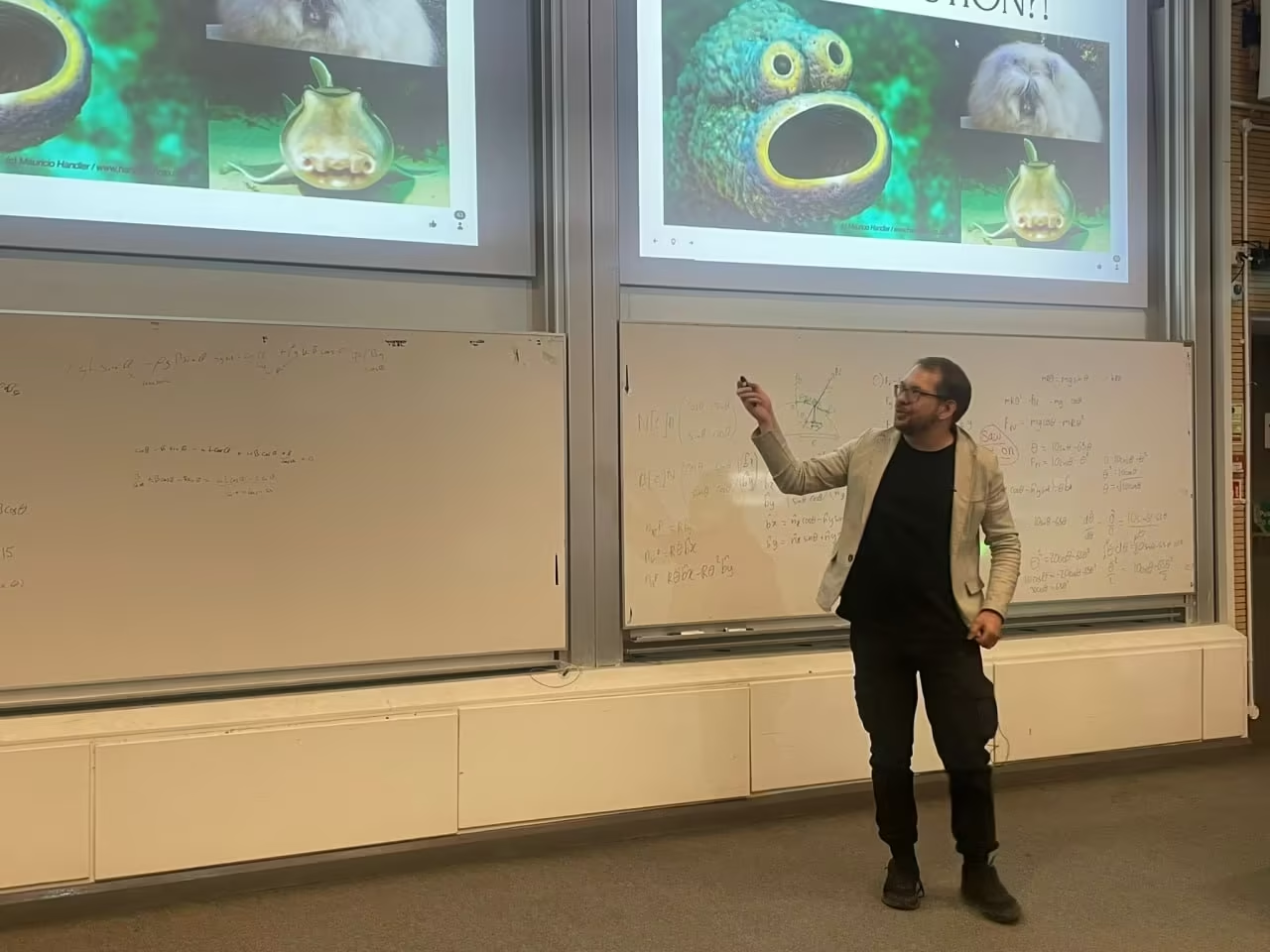

Alexander Panchin’s lecture at the Mason Leasure Theatre was completely sold out. Open public lectures are a popular format, and it’s easy to see why: the speaker, striving to convey the essence of their thoughts, often uses vivid, unexpected, and often humorous comparisons and analogies.

A well-known science communicator and author of books debunking pseudoscientific paradigms, Panchin came to London with a provocatively titled program: “Playing God: Has Science Crossed the Line?” One might expect a sermon on scientific atheism sprinkled with quotes from materialist Ludwig Feuerbach—but not at all. A regular viewer of Panchin’s YouTube channel knows exactly what to expect: a fact-filled, detail-rich lecture, not a philosophical free-for-all.

“Scientists are playing God, and they’re bound to go too far. Today, I’m going to explain why scientists aren’t playing God—they’ve already outplayed Him long ago. We’re doing things that simply don’t occur in nature,” Panchin said at the start.

What followed was a dense, two-hour stream of facts, comparisons, and conclusions.

Of course, genetically modified organisms (GMOs) came up—often feared by the public. Panchin explained that nature itself regularly performs the same processes: “We are all mutants compared to our parents; gene mutations happen constantly.” Natural gene transfers exist, he said, pointing to the sweet potato: “All sweet potatoes contain genes of bacterial origin.”

The lecture was accompanied by a well-crafted visual presentation—clear, humorous, and most importantly, interactive. The audience could access the slides via their smartphones and participate in polls on key topics: Would you want to carry a child in an artificial womb? Would you choose the healthiest embryo—or one with specific physical traits? The crowd responded with laughter, clearly enjoying the unexpected results.

Panchin, a seasoned speaker and scientist, knows that a joke often works better than a slogan. When talking about transitional forms in evolution, he showed a hilarious hybrid of a motorcycle and a car—an absurd contraption that could’ve come from the dystopian worlds of the Strugatsky brothers:

“They might not be very functional or viable! That’s when the engineer steps in—and that’s where genetic engineers get accused of ‘playing God.”

In two hours, with humor and clarity, Panchin not only introduced the audience to the latest scientific breakthroughs, but also explained basic concepts—DNA structure, the Dolly the sheep experiment, and how different countries regulate scientific progress. He made sure not to assume everyone in the room was a biologist.

He also touched on practical uses of genetic experimentation—for example, how a virus shell that can enter a specific organ might be used to deliver medication directly to that site.

Scientists, Panchin said, are doing phenomenal things—intervening in the very fabric of life, in the DNA molecule itself—and he showed how elegantly they can alter the rules of genetic complementarity.

It seemed no one in the room disputed the value of scientific progress. Still, audience polls sometimes yielded surprising results. When asked whether a scientist should face prison for conducting unnecessary (but non-harmful) research, the winning answer was unexpectedly:

“God will judge him”—and the audience burst into laughter.

He also spoke about prenatal—or perhaps pre-prenatal—genetic engineering: such as creating a child from three parents by replacing a faulty part of a cell with a healthy one from a third donor. He described experimental mice born from two males—though a female was still needed to carry the pregnancy.

Artificial wombs were also discussed (accompanied by a slide of a hoofed fetus inside a complex plastic bag). They work, but current technology only shortens pregnancy by about three months; it can’t yet replace the entire process. Why not? “We don’t know yet,” Panchin said. “Only theories exist so far.”

Naturally, the audience had questions. One asked: who’s to say these brilliant genetic ideas weren’t implanted in scientists’ minds by God Himself? Another asked where the moral and ethical lines of experimentation should be drawn.

Panchin responded thoughtfully, especially regarding genetic testing for prospective parents:

“Routine tests cover the vast majority of genetic disorders. There are rare ones—you can do full genome screening and consult a specialist to check for anything unusual. It costs about $1,000, which isn’t much, considering the cost of childbirth and raising a child. The question is: how much is that worth to you? Maybe those same funds would be better spent on education or healthcare for your future child.”

As a media outlet focused on culture and the arts, we couldn’t resist asking Panchin about talent and science:

—If we manipulate the brain, can we create a Titian?

—Of course, genetics can influence abilities, including creative ones. But we don’t know how to tweak the brain to turn someone into a da Vinci. That’s the problem—everyone’s neural connections are different. We don’t know how neurons are interconnected in one person, let alone how to combine two people’s neural networks. Even their total neuron counts may differ.”

After the lecture, Panchin signed books and continued chatting with attendees. Forgive me, serious scientists, but history seems to be circling back again—in the 14th century, the Pope banned alchemists, yet they kept working in their laboratories, which were so different and yet so similar to today’s high-tech labs. They made mistakes, searched, and sometimes discovered. There was less knowledge then—but the thirst for science was the same. And, by the way, finding gold or the Philosopher’s Stone was important, but not the ultimate goal. The ultimate goal was man—to elevate him to new, unreachable heights. Because in the end, that might still be science’s greatest mission.