On a cool January evening in London’s West End, the Harold Pinter Theatre—built in the late 19th century and preserved almost in its original state—is buzzing with people, many of them children. There are still ten minutes before the show begins, yet the dimly lit stage already seems alive: cicadas chirp backstage, melodious xylophone notes resonate, and occasionally, the soft toot of a train whistle can be heard. White confetti is scattered along the aisles, hinting at snow—setting the stage for the spectacle that is about to unfold.

Slava Polunin’s “SnowShow”: The ‘Snowy’ Magic of Foolery, A Blizzard of Freedom

The show begins with the entrance of Slava Polunin, a lonely, weary clown with a silent gaze. He wanders across the stage in confusion and melancholy. But the sadness doesn’t last long; soon, the clowning escalates into a radical, almost anarchic expression of humour. Vibrant colours, soap bubbles, and carnival-like scenes exude an atmosphere of absolute freedom. The performers push boundaries, breaking the audience’s personal space: they walk on the backs of seats, leaning on the audience’s hands, drench spectators with water, and enshroud the hall in a massive web that drapes over everyone’s heads.

The first act is pure farce! Adults, in particular, react cautiously—it feels awkward to watch performers so shamelessly embrace silliness. Sure, everyone laughs on cue and claps when expected, but there’s a palpable sense of discomfort, a stiffness in the air. How deeply ingrained are our insecurities if simple clowning makes us squirm in our seats? Laughter becomes a weapon against people’s inhibitions. Words aren’t needed here; the only one in the entire show is a crooked, old lamp displaying the word “Interval” for the intermission—and even that, it seems, is stolen by one of the characters in the second act.

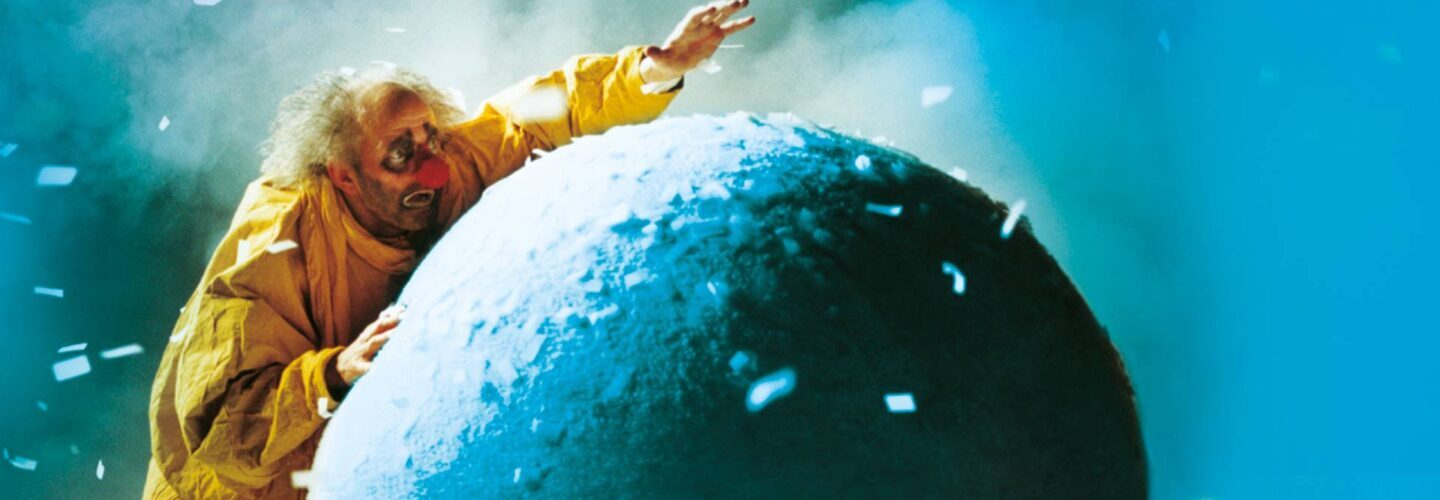

After the intermission, Polunin returns to the stage, and everything changes: the silliness gives way to quiet drama, and the performance gains a poignant depth. The climax of the show sees the lonely clown suddenly opening the backdrop, revealing a massive fan that unleashes a snowstorm throughout the auditorium, illuminated by dazzling spotlights, all set to Carmina Burana. (I wonder if Polunin considered the wordplay between “burana” and “buran”, “blizzard” in Russian?) The audience is instantly buried under paper snowdrifts. On stage, the small figure of an elderly clown struggles against the unstoppable force of the storm—a touching moment. But the audience, captivated by the snowy spectacle, seems to overlook the drama: children shriek with joy, parents laugh, and snow flies in every direction.

The show culminates in a jubilant celebration: all the clowns emerge, throwing giant, colourful balls into the audience, which bounce off walls, heads, and hands. Snow continues to swirl, children scream with delight, and parents record the chaos on their phones. A little boy in the aisle gathers a snowdrift from the paper flakes… Meanwhile, Polunin sits serenely at the edge of the stage, watching the mayhem with a contented, blissful smile.

***

As I leave the theatre, I try brushing the snowy confetti off my hair and clothes. Outside, one of the actors—a Frenchman with pink hair who has been performing in the SnowShow for 17 years—is singeing pieces of wood with a lighter. It turns out he uses charcoal to apply his makeup before every show.

I get a chance to speak with Slava himself. He steps out through the stage door—a small man with a grey beard, a quirky backpack, and a knitted hat adorned with three tassels.

Slava, the “SnowShow” has traveled the world for over 30 years. Has it changed over time?

“It’s important to understand that the SnowShow isn’t just a performance; it’s a slice of life. So yes, it has changed because we’ve changed. But clowns are special characters—they don’t think about the past or the future; they live entirely in the here and now.”

You’ve taken a break from London but have finally returned. Will you stay for long?

“Yes, we haven’t been to London in seven years, but now we’ll be here every year!”

What do you dream about?

“Whatever I dream about, I do immediately.”

(I hesitate for a moment.)

Can I hug you?

(He smiles broadly.)

“Of course!”

The tassels on his hat tickle my face.

***

After the performance, I find myself reflecting on Polunin’s words: clowns live in the present, free from the burdens of the past and future. This idea brings to mind two scenes from the show that left a lasting impression.

In one, a character in a whimsical hat and an old coat drags a string of miniature houses across the stage. Each tiny house looks like it belongs in a fairy tale, with glowing windows, snow-covered roofs, and an aura of warmth and coziness.

In another, Polunin’s character leaves his home—clearly for the last time. Holding a letter, he reads it sadly, then slowly tears it into pieces, tossing the fragments into the air, transforming them into snowflakes.

How symbolic! Letting go of the past and parting with cherished memories can be incredibly hard. But life is the moment unfolding right now, and it holds its own magic. Polunin and his clowns seem to remind us not to cling to the past or obsess over the future. “Whatever I dream about, I do immediately…” The clowns of the SnowShow are our guides to freedom. Through laughter and play, they teach us to let go and live in the present. In this eternal “here and now,” Slava Polunin offers everyone the chance to be a little happier and a little more human in a cold world.