The Lockpick to “Lolita”. The Challenges of Nabokov’s translation

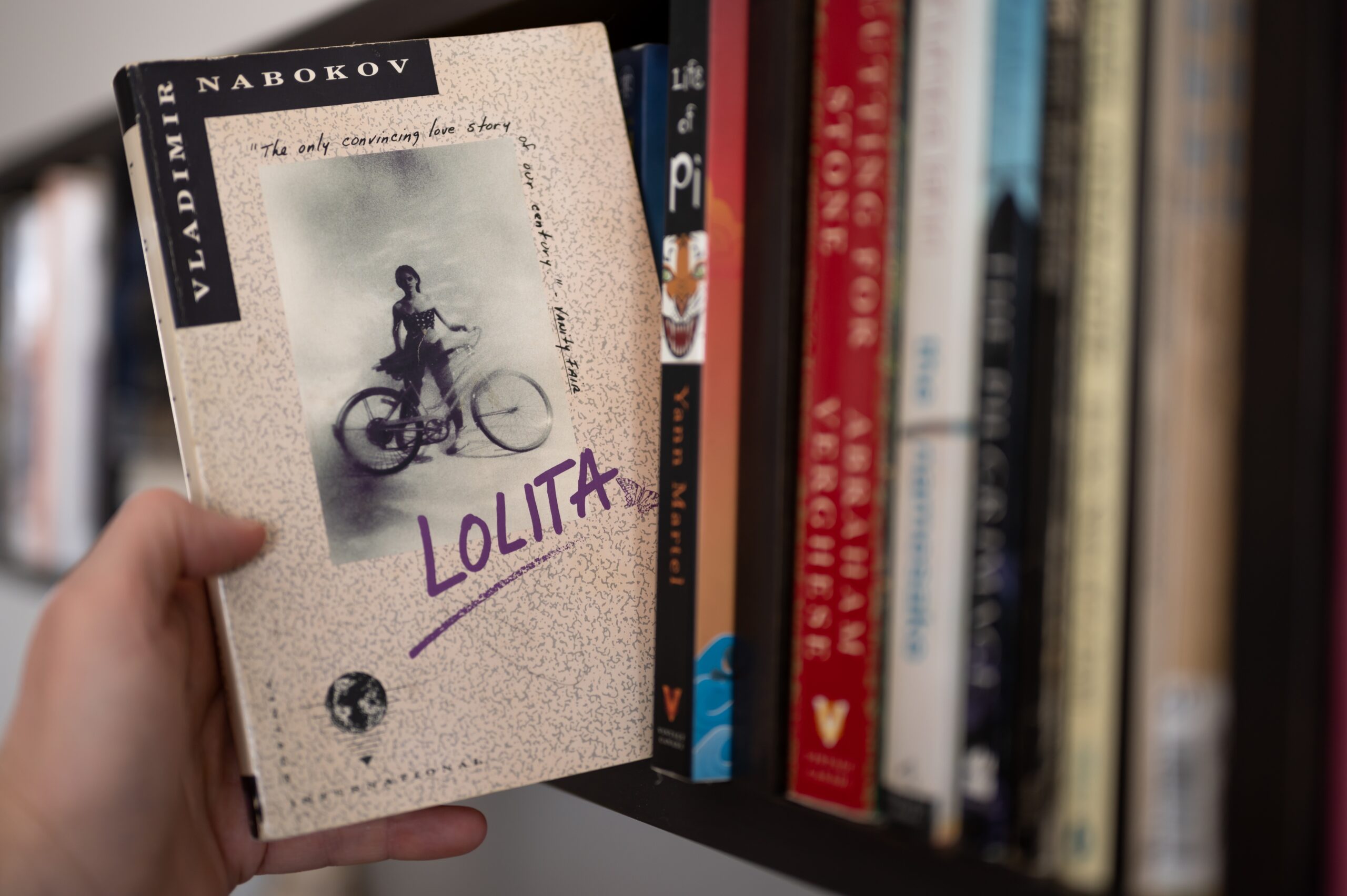

Publishing novels in English in France has long been sort of a tradition. We spoke about “Ulysses,” the famous novel by James Joyce, which was banned by censors in the UK and the USA and published by Sylvia Beach in Paris in February 1922. Vladimir Nabokov’s “Lolita” was published in France in 1955 as part of the “Passenger’s Companion” series by Olympia Press. While critics referred to “Ulysses” as “a heap of dung, crawling with worms, photographed by a cinema camera through a microscope”,” Lolita received no less harsh criticism. “The filthiest book I have ever read” ,” wrote the Sunday Express. What readers of Olympia Press, a publisher of semi-pornographic literature, thought about “Lolita,” and whether anyone among them read the novel to the end, we are unlikely to ever know.

Nabokov complained in a letter to Graham Greene: “From various friends I keep receiving heart-warming reports on your kindness to my books … My poor Lolita is having a rough time. The pity is that if I had made her a boy, or a cow, or a bicycle, Philistines might never have flinched. On the other hand, Olympia Press informs me that amateurs (amateurs!) are disappointed with the tame turn my story takes in the second volume, and do not buy it”

In the afterword to the American edition, Nabokov writes: “My private tragedy, which cannot, and indeed should not, be anybody’s concern, is that I had to abandon my natural idiom, my untrammelled, rich, and infinitely docile Russian tongue for a second-rate brand of English, devoid of any of those apparatuses–the baffling mirror, the black velvet backdrop, the implied associations and traditions–which the native illusionist, frac-tails flying, can magically use to transcend the heritage in his own way”.

However, the greatest gift that awaited all future translators and philologists was Nabokov’s translation of his most notorious novel back into his native tongue:

“I imagined that in some distant future somebody might produce a Russian version of Lolita. I trained my inner telescope upon that particular point in the distant future and I saw that every paragraph, pock-marked as it is with pitfalls, could lend itself to hideous mistranslation. In the hands of a harmful drudge, the Russian version of Lolita would be entirely degraded and botched by vulgar paraphrases or blunders. So I decided to translate it myself”.

And when he finished the translation, he wrote a completely tragic commentary: “…story of this translation is the story of a disappointment. Alas, that ‘wonderful Russian language’ which, I imagined, still awaits me somewhere, which blooms like a faithful spring behind the locked gate to which I, after so many years, still possess the key, turned out to be non-existent, and there is nothing beyond that gate, except for some burned out stumps and hopeless autumnal emptiness, and the key in my hand looks rather like a lock pick”.

This metaphor, due in no small part to its poignant relevance, brings me a sense of despair and sorrow, but what is a disappointment to Nabokov is a treasure and methodological material for a linguist.

Lolita is a Spanish name derived from “Dolores”, which means sorrow, in honor of Our Lady of Sorrows. “My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta”. In the third syllable the “t” sound is pronounced according to Spanish or Russian pronunciation. In English the tip of the tongue touches the alveolar ridge; in Russian, it touches the upper teeth.

“My purest, most abstract, and meticulously constructed book,” Nabokov said of the novel. “I am probably responsible for the odd fact that people don’t seem to name their daughters Lolita any more. I have heard of young female poodles being given that name since 1956, but of no human beings”

Reading “Lolita” is both a stylistic pleasure and hard work. It is a struggle against the siren song of Humbert, so subtly and unobtrusively offering us his worldview. As Vladimir Propp wrote in his diary: “Literature is powerful because it evokes an acute sense of happiness… Happiness ennobles us, and this is the significance of literature, which makes us happy and thereby elevates us.”