The Observer of Nature: Van Gogh exhibition at the National Gallery

On the 14th of September National Gallery opened an exhibition of Vincent van Gogh to mark two occasions: its bicentenary, as well as the centenary of the acquisition of two Van Gogh masterpieces – The Chair (1888) and Sunflowers (1888). Interestingly, both paintings were created during the period Van Gogh spent in Provence, France – and it is around this time that the new exhibition, which runs until 19 January 2025 and is already sold out, creates its main themes.

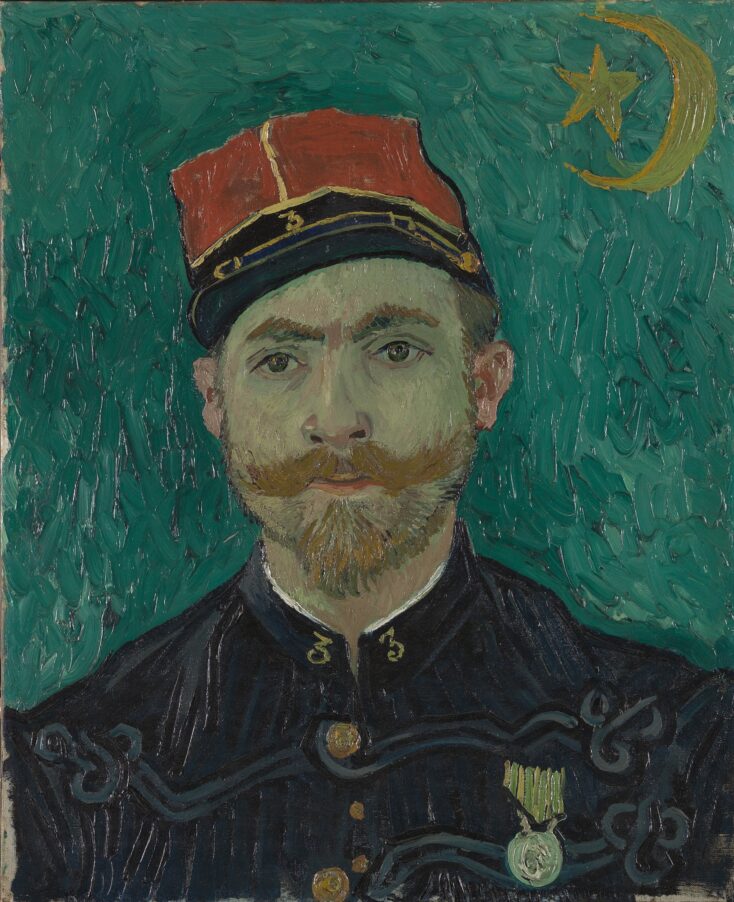

The curators have titled the exhibition “Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers”, and this title seems a little vague, unclear, despite the fact that the exhibition does begin with the paintings “The Poet (Portrait of Eugène Boch)” and “The Lover (Portrait of Lieutenant Milliet)”. This theme remains an artificial umbrella for the paintings of this period and does not fully convince despite the best efforts of the curators.

Despite the richness of the paintings one could see here, many of which connoisseurs of the artist will indeed see for the first time, the overall structure of this exhibition is unclear and blurred. Nevertheless, one can try to get a feeling of the atmosphere and the general theme of the exhibition by wandering through its six really crowded rooms.

Undoubtedly, its main focus is the nature of Arles, Saint-Rémy-de-Province and their gardens, mountains, paths, farm fields, trees, neighbourhoods. The exhibition brings together works limited to just two years – 1888 and 1889 – during which Van Gogh rented a small house in Arles (represented in the exhibition by the painting “The Yellow House (Street)”). Here he wanted to set up an exhibition of his works, making idealistic plans for an artists’ colony here.

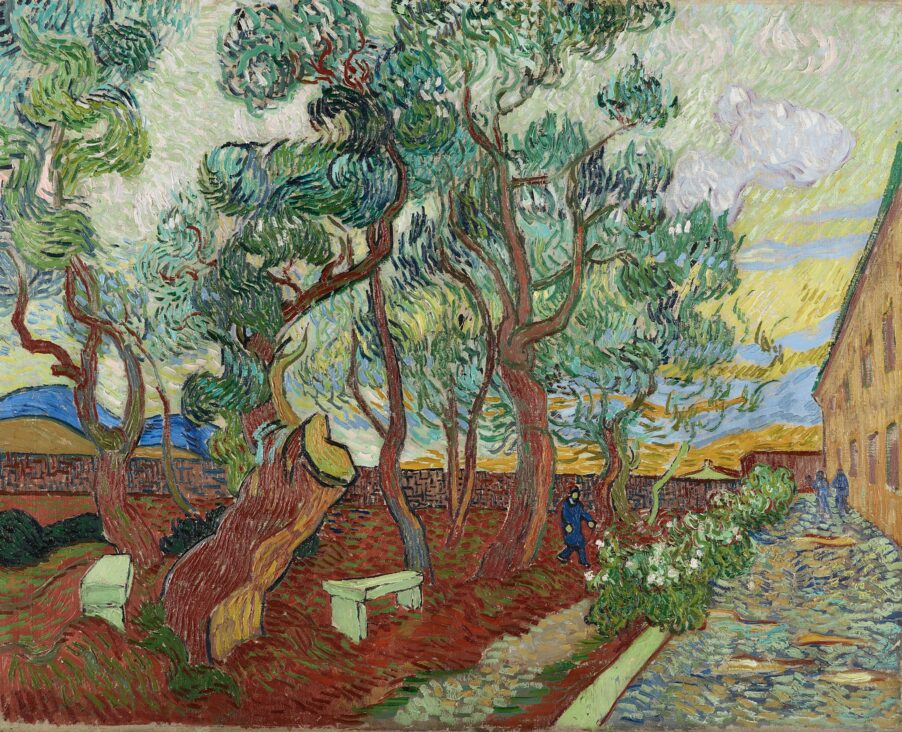

In San-Rémy Van Gogh spent several months in a psychiatric asylum, and we can see its courtyard and garden in the paintings “The Garden of the Asylum at Saint-Rémy” (1888), “The Park of the Hospital at Saint-Rémy” (1889), “Trees in the Garden of the Asylum” (1889) and several drawings of the latter. Incidentally, one room is devoted to the drawings, with a number of views from Mount Montmajour near Arles, and we learn that the local garden may have reminded Van Gogh of an episode from Zola’s novel.

The most significant curatorial achievement of the exhibition is bringing together three paintings – “Sunflowers” owned by the National Gallery, “Sunflowers” from Philadelphia Museum of Art that has left the museum for the first time, as well as “La Berceuse (The Lullaby)” from Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. If letters to his brother Theo are to be believed, Van Gogh planned to place them together for his first exhibition. Visitors are also impressed by the sheer number of museums, with paintings coming from Holland (not only Amsterdam, but also the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo), the USA, Japan, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, as well as private collections and owners.

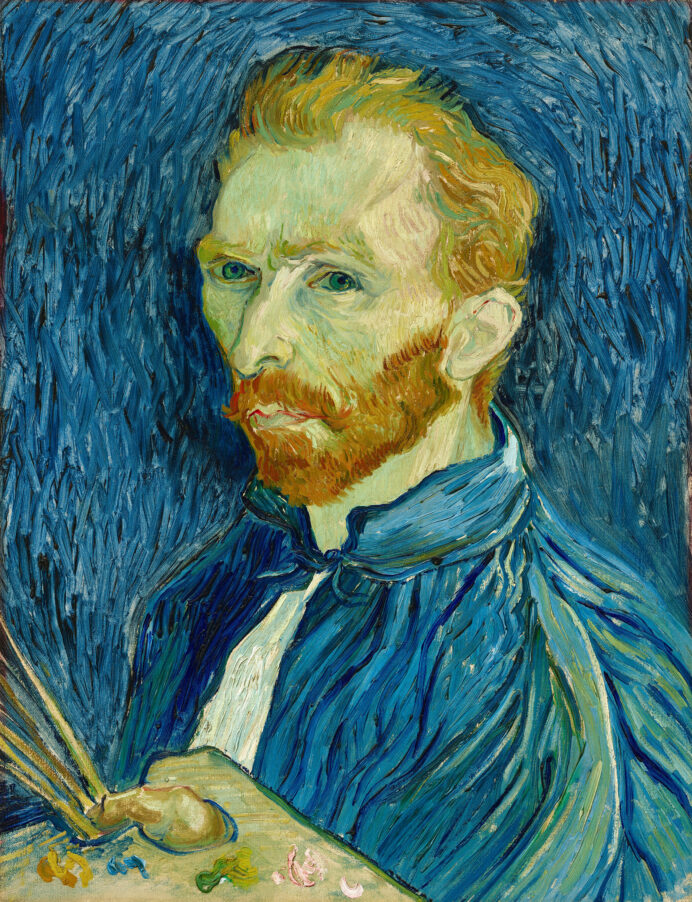

Even after the vast exhibition at Orsay last year, that brought together works from the last months of the artist’s life, connoisseurs will be surprised by paintings they may never have seen. Thus, surprising by its minuteness is “Roses” (1889) from the National Museum of Western Art (Tokyo), the Self Portrait (1889) of the artist from Washington will amaze by its unfamiliarity to our eyes, and The Sower (1888) from Zurich will reflecting the artist’s well-known passion for Oriental art.

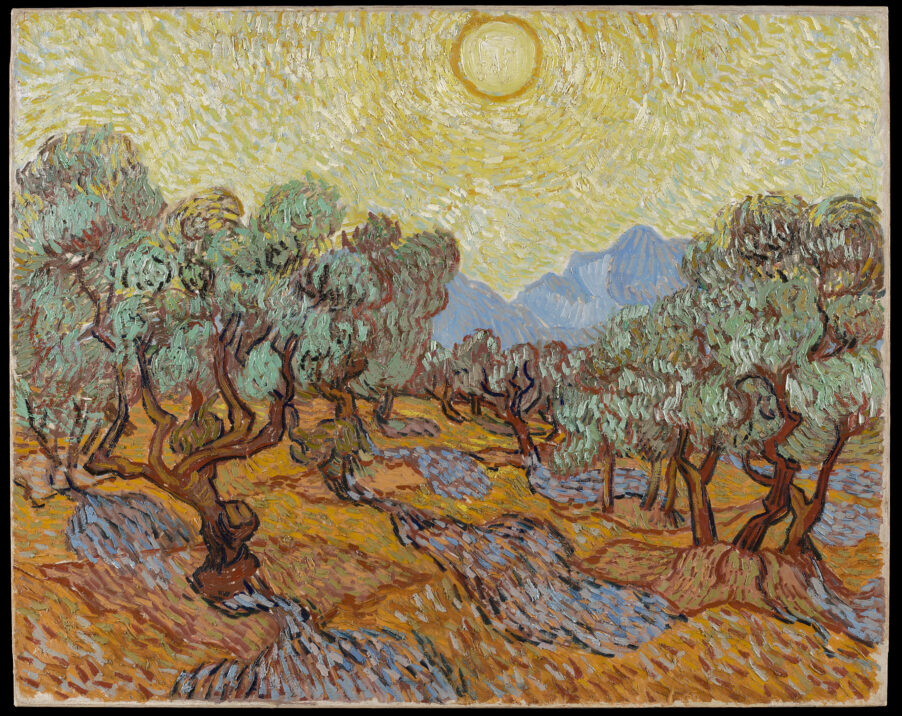

The last room – “Variations on a Theme” – is also eye-catching, as it reveals the artist’s interest in exploring similar motifs. He likes to try out his own compositions again to create their new variations, with different colour tones each time. Van Gogh does several paintings of the same landscape – the same garden or the same farmer’s field. Interestingly, in the the letter to his brother the artist admits to the difficulty of conveying the colour palette of the olive fields, and then we can trace, looking at five different paintings of them, how exactly Van Gogh searched for the keys to their interpretation on canvas.

Judging by the individual quotations appearing on the walls of the exhibition (apparently, the additional information has to be acquired through a paid audio guide), the curators wanted to convey the poetic influences of certain literary works and figures on the artist. But they got an unexpected, almost the opposite result. These gardens of poets (where, perhaps, Dante and Boccaccio could walk), these uneven rows of trees in Arles, these shaky diagonals of Provence fields – they reflect not literature and not poetry as such, but the complex inner world of the artist himself. Yes, we see his paintings from private collections, and we can then search for the places in Arles and Saint-Rèmy where they were painted – unlike Orsay, the National Gallery has not done the curatorial work of finding these locations and leaves this research to us.

But the important thing is that in these lines, in these colours, or rather inflorescences, in this very recognisable palette of Van Gogh, the artist himself becomes strongly visible – we, as always, receive a pathway inside his head and his world. And our heads spin from this contact. As always with Van Gogh. And this is Van Gogh – a subtle poet, observing nature, striving to convey its smallest shades, but still showing himself in trying to convey them. This is Van Gogh – not only a poet but also the lover from the title of the exhibition, that is, he himself is all those “Poets and Lovers” that the curators tried to find around him, and this love is directed not at humans, but at nature.

There are so few portraits here – the rare exception being two versions of “L’Arlesienne” from Rome and a private collection – and we leave the exhibition full of colours, curves, connections and lines in which Van Gogh and his unique vision of the world and nature have been revealed to us. Yes, the path through his works has been only sketched out by curators, but the richness of the works in the exhibition still makes it a must-see.

The exhibition is on until the 19th of January.