John Galsworthy’s “The Forsyte Saga” is a grand novel of immense and utmost importance not only to English but also to world literature. A Nobel laureate, Galsworthy wrote about what he knew best—people, their loves, and desires. The vivid depictions of the Forsyte family members and everyone connected to them have intrigued directors from the very beginning. Nine books across three volumes—how can one truly encapsulate this Homeric narrative within the confines of a single artistic work?

The Pain of the Family System. The Forsytes as a Mirror of Pain

In film and television, the adaptation seems somewhat manageable with the ability to shift scenes from one location to another, and the potential to create a genuine multi-episode series. However, in theatre, such luxuries are absent, and a stage adaptation of the great novel had long been unattempted.

Galsworthy spent many years meticulously crafting the universe of the Forsytes, passionately detailing each character. Perhaps this is why every reader has their own vision of the Forsytes, and any stage adaptation tends to meet with significant resistance from a substantial portion of the audience. The indignant cry of “It doesn’t look right to me!” sounds almost childlike, as in pure perception, it’s essential for the hero to resonate precisely with one’s favored depiction of the character. And not loving this great novel seems almost impossible. Each cinematic portrayal of Irene suffers because Galsworthy modeled the main character after his wife Ada, enriching the character with hundreds of recognizable details. It’s an attractive yet perilous role!

And now, in 2024, Josh Roche undertakes to stage the epic at London’s Park Theatre. But how? How can such a novel be crammed into the narrow confines of a stage? The director finds a harmonious and elegant solution by splitting the narrative into two plays. You can spend either a whole day or two evenings with the Forsytes—the choice is yours. Rosh explores each generation meticulously, which is why the first play is titled “Irene” and the second “Fleur.”

The staging by Sean McKenna and Lynn Coglan is truly magnificent, not turning the play into a digest nor thoughtlessly cramming it into a Procrustean bed of allocated time, but preserving the atmosphere, spirit, and—crucially—the characters. The characters are so intricately portrayed that one wants to keep watching them. The intimate setting of the small theater turns the audience into participants, albeit silent ones. This strange but clearly directed sense of inclusion in the Forsyte circle makes the experience both sharper and more surreal, at times making the audience not just observers but accomplices—after all, the Forsytes love secrets, practically turning it into the play’s slogan.

On an almost bare stage — just chairs and lamps occasionally appearing—walk Galsworthy’s characters. And here lies a unique trick, similar to “Anna Karenina”—everyone knows what happens to the heroine in the end, but the play or film based on Tolstoy’s novel compels the audience to watch for entirely different reasons. Thus, these Forsytes become a kind of revelation to the audience, despite most being well-versed in the plot twists.

Forsytism—the philosophy of ownership against which Galsworthy wrote all his texts—is explored here not so much from a financial well-being perspective as from a human relations standpoint. “The Owner,” precisely the title of the first novel in the saga, threads through both plays like a red line. The thirst for ownership replaces love, anger eclipses pain, aggression destroys any attempt at understanding.

The costumes are beautifully precise. Irene’s dress, expensive and intricate, rustles with silk and ribbons, shining—it’s a candy wrapper, not a dress. Her friend June’s dress—a check pattern, coffee brown with a strict velvet trim—oh, how simple and everyday she appears, and how precisely Florence Roberts plays these unfair distinctions.

Finally, we get to the actors. The entire troupe’s meticulous work is evident, but there’s another important detail that cannot be overlooked. Throughout all the roles, like tiny sparkling diamonds, are reminders of previous performers. No, I’m not talking about copying or homages—it’s much subtler and more interesting. It’s a rethinking of the experience of previous acting efforts, where they serve as a foundation, a point of reference.

Fione Hampton, playing Irene, faces the toughest challenge. The word “beautiful” is uttered so often in reference to Galsworthy’s heroine that she must embody not just external beauty, which is evident, but also its reflected qualities—the weight of this beauty, her golden shackles. In modern terms, she plays objectification, and at times, she evokes Greer Garson in the 1949 film adaptation, which aptly was called “That Forsyte Woman.” There’s something of Chekhov’s Elena in her portrayal—particularly evident in the same fatigue, the same heavy habitual misery, the same loneliness. She falls for the young architect Bosinney, her friend’s fiancé, not because he is extraordinarily handsome, but because he is different. Not a Forsyte. That seems to be enough.

But with her, he is so timid that he can’t believe his luck—as if this radiant woman, descended from some dazzling staircase, could love him, a mere working man. Andy Rush, more reminiscent of a character from a completely different era, book, and universe — curly-haired, fluffy Snufkin in a crumpled coat and green hat, somewhere lost his harmonica. Such a Bosinney could not but be run over by the cruel world of the Forsytes — perhaps even literally by a cab wheel emerging from the fog.

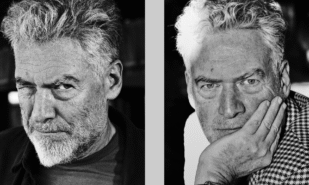

Another central character — Soames Forsyte. An owner, obsessed with passion, towards whom his wife Irene feels a physiological repulsion. Joseph Millson plays Soames—there’s nothing repellent about him as with other performers of this role. But the way he moves—like a wolf, turning his whole body towards Irene, his hands becoming predatory paws, he hunches and tilts his slick, pomaded head in stubborn rage. And with every minute, from a likeable person, he transforms into a monster, assaulting his own wife and never repenting for the rest of his life. It’s interesting that this isn’t Millson’s first encounter with the Forsytes — he voiced Soames in a long-running radio adaptation.

Lacking decorations, the plays are rich with fascinating mise-en-scènes, led by Fleur Forsyte — Soames’ daughter (Flora Spencer-Longhurst). In the first play, she moves across the stage unseen—because at that time, she wasn’t even born yet, simply slipping into the past in hopes of unravelling her own pain. The second play is about her, about her passion, about her possessiveness. Fleur, passionately in love with Irene’s son Jon — her father’s daughter, as if the play says, look how the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree… But again, it’s much more complex and subtle. By the director’s will, John is also played by the same Andy Rush who plays Bosinney, the same otherworldly poet (and indeed, Jon writes poetry).

The family system, its pain, horror, and love—turn children into their own hostages. It’s not the children who answer for the sins of the parents; it’s the parents who ruin the lives of their children. Irene and Somсs transmit mutual hatred to the next generation, denying their children a life. Through deception, manipulations, they drive their children apart—and make them miserable. And although Fleur, consumed by the same uncontrollable passion as her father, seduces her lover almost by force in this interpretation, he will still leave, leave without looking back.

But here is Soames — and Millton plays Soames in both plays, traveling the path from a young man to an old man with white hair—falls on the red plush carpet and lets out his last breath, his fingers still tightly gripping Fleur’s shoulder—will not let go, will not release, will not allow.

The genetic kinship of the novel, the play, and all the films makes the audience reflect not only on the eternal nature of ownership but on empathy and the impossibility of justifying violence in any form.