This is a reunion — a return of the 2017 sensation. Girl From the North Country once swept up awards, nominations, and full houses on tour. Its author — the playwright, director, and storyteller behind the entire stage tapestry combining the Great Depression and Bob Dylan’s songs — is Conor McPherson, whose latest play The Brightening Air was recently staged at The Old Vic with great success. And now, McPherson brings back his hit jukebox musical — directing it once again himself.

The Siren of the Icy Lake: The Return of the Bob Dylan Musical at The Old Vic

We’re in 1930s Minnesota — a bleak time of the Great Depression. The heavy waters of vast Lake Duluth, bankruptcies, poverty, despair. What does any of this have to do with Bob Dylan? Everything: his childhood unfolded near Lake Duluth. It’s a place that’s almost always cold, damp, and dark — harsh climate, harsh life. The lake in Girl From the North Country is a full-fledged character in its own right, with its own will and mood.

On stage stands a shabby guesthouse. In its rooms live boarders — fragments of who they used to be. Each carries their own catastrophe. These people are the generation of Dylan’s parents — and somewhere in the womb of the innkeeper’s daughter, a future Dylan-like child grows.

Stuff a group of desperate people into a godforsaken guesthouse like mice in a jar — and see what happens. Remember the famous experiment? Mice were placed in a terrarium and sealed with a transparent lid. At first they jumped and scratched, trying to escape, but the lid blocked them. Then the lid was removed — and yet neither the mice nor their offspring ever tried to get out again. The invisible barrier remained. That’s what learned helplessness looks like — and that’s what Girl From the North Country is really about. Who will break free, and who will remain trapped? O you, enchanted lake! Everyone is fragile here; there’s so much love, so much damage — no whole hearts remain.

The hotel owner, Nick Laine (Colin Connor), is drowning in debt; the building will soon be seized. His wife Elizabeth — raw nerve and broken porcelain — is suffering from early dementia. She peers out from between the slats of illness like a fragile pearl, but those slats close tighter and tighter.

Their hapless son (Colin Bates) — a drunkard and poet — is losing the love of his life. Their adopted daughter, Marianne (Justina Kehinde), stunningly beautiful, is pregnant by a man she won’t name. The Burke family — mother, father, and their adult son Elias (Steffan Harri) — are odd in their own way: Elias behaves like a 3-year-old, always smiling beneath a suffocating knitted vest.

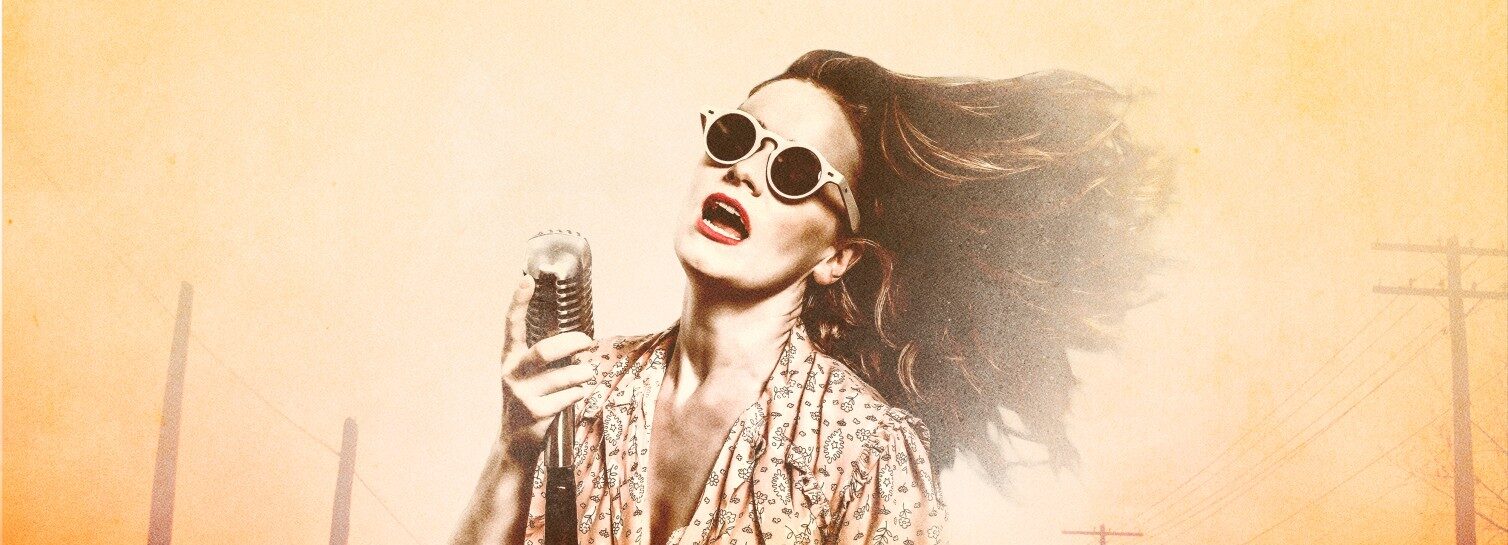

But musical theatre, by nature, doesn’t allow the actors to break fully into drama — or into tragedy. The rigid timing (damn it!) permits just one pin in the carefully stitched fabric of Dylan’s songs. There’s no time to add folds or deepen the seams. A Dylan song. Then a short dramatic scene that nudges the plot forward. All of this is strung along the narration by Dr. Walker (Chris McHallem), who stands calmly at a vintage mic in a noir-style fedora, recounting this tale the way a doctor might present a case at a clinical meeting.

Song – drama – song – drama. With each number, the lighting shifts; actors’ faces glow with strange beauty as they gather around vintage microphones in warm amber twilight. And poor Elias — he suddenly becomes sharp, mature, ironic, pulling a harmonica from his pocket. It’s no longer a toy, but an instrument — a clear homage to Dylan.

The songs have been rearranged, of course — but that very unfamiliar sound is the link between the 1930s and the 1960s, when most of them were written. The atmosphere thickens with each stitch, each song, each set change. Sheer curtains rise and fall, revealing either bleak Minnesota landscapes or dingy hotel interiors. A table at center stage appears and disappears. It should symbolize togetherness — mealtimes, quiet conversation — but here, it evokes something else entirely.

When the guests gather around the table for Thanksgiving, a dreadful sense of doom thickens in the air — you can almost touch it. And yes — thunder cracks, sudden and brutal. The tragic core becomes the brilliant Mrs. Burke and her husband — the bearded Mr. Burke, who maintains a shred of elegance even in ruin (David Ganly). Ganly, a gifted dramatic actor, plays with subtlety and inward power. He builds his character’s arc carefully, within the narrow confines of a musical. And we witness the tragedy of his son through the prism of his own dark relief — a crime born of grief and panic. But then — snap! — a cut to the next moment, and suddenly the couple is packing to leave the inn, as if memories were erased. As if nothing happened.

And of course, the main demon here is the traveling Bible salesman — Marlowe. He arrives in the middle of a storm. Lightning flashes across his sharp face, thunder roars ominously. Eugene McCoy, who just played a stellar Prince Andrei in Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of 1812 at the Donmar, now appears at The Old Vic as Marlowe. With his jack-in-the-box energy, you distrust him instantly. Sloped shoulders, slicked-back black hair, a condor’s profile, a stalking gait. The character is vivid, precise, and unmistakably drawn. No one believes him — but no one has the strength to resist. Everyone is too burdened by their own demons. He is, of course, a classic trickster — and just as classically, vanishes with the storm.

There’s something here of a Russian play from the early 20th century — Gorky’s The Lower Depths — and of Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh. It’s a wandering, haunted narrative. And where better to gather broken souls than a failing hotel?

Because of the musical’s structural rigidity, the audience never fully sinks into the characters’ inner pain. Instead, we watch from a slight distance — as if from the far shore of the icy Lake Duluth. Where will they go? What will happen to them? How will the winds scatter them?

The final word belongs to the Laine family — husband and wife. And here, it becomes clear: the true central character is Elizabeth Laine. This is her story — her descent into illness, as into the icy depths of the lake. Katie Brayben plays her with fearless physicality — at times childlike, at times monstrous. Then suddenly, she becomes magnetic — not a sea siren, but a lake siren. McPherson writes her like Homer wrote his. Wild, chthonic Elizabeth with a trembling knife in her delicate hand suddenly turns soft, golden, playful. The shell of her mind opens and closes — and we’re left unsure where the real Elizabeth is.

Poor, poor Dr. Walker — what a difficult patient he had. A life that resonates so deeply with Dylan’s iconic lyrics:

When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose

You’re invisible now, you’ve got no secrets to conceal

How does it feel, ah how does it feel?

To be on your own, with no direction home

Like a complete unknown, like a rolling stone.