The story of one masterpiece: reconstructing the story of Bolero’s creation

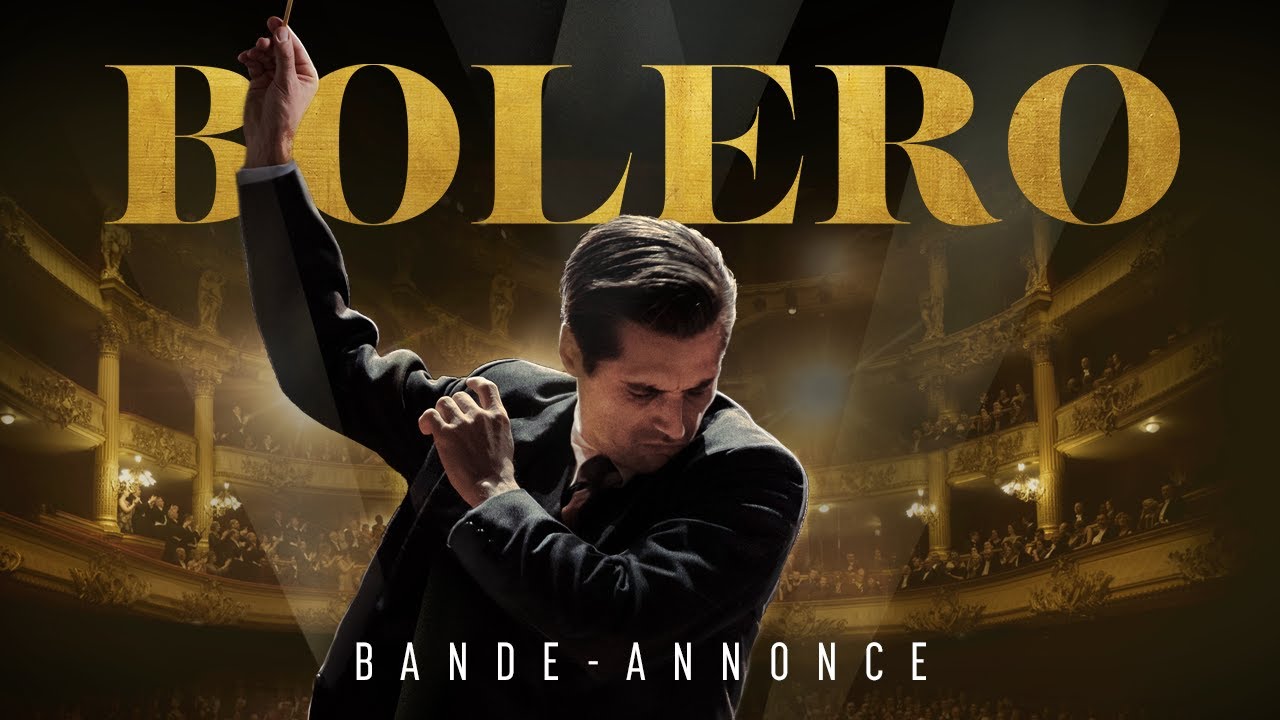

Actor Raphaël Personas, who plays Maurice Ravel in a new film, Bolero, by Anne Fontaine (released in France in March 2024), looks a bit like Cillian Murphy, having a similar piercing gaze. The new film, paradoxical as it may sound, can be compared to “Oppenheimer.” Anne Fontaine’s biographical film, similar to Christopher Nolan’s historical epic about the creation of a project that changed the course of world history, shows how the life of one genius is thrown into the furnace of a single work that, in people’s minds, will forever be associated with his name.

Surely, musicologists know and value many other magnificent creations of this composer. Maurice Ravel also composed the famous Piano Concerto for the Left Hand (1930), written for Paul Wittgenstein, who lost his arm in the war, the orchestral suite Le Tombeau de Couperin (1917), and the magnificent and innovative one-act opera-ballet L’enfant et les sortilèges (1925). Still, when we say “Ravel,” we think “Bolero.” It is mentioned in the film’s end credits that every fifteen minutes, Ravel’s Bolero is performed somewhere in the world. Also, as we will see in the opening credits, there are many arrangements and interpretations of Bolero in all kinds of genres, including rap, disco, and folk music. Anne Fontaine, also known for her biographical film about the rise of Coco Chanel, starring Audrey Tautou, was inspired by the biography of Ravel written in 1986 by musicologist Marcel Marna. From this source, she picks one particular thread and, in her film, aims to show how the composer’s character and professional qualities, as well as the feelings, circumstances, and even accidents that possessed him, led to the creation of Bolero. This results in a quite convincing and fascinating epic story, generally staying within the audience’s expectations of a biopic and allowing us to gain new insights into Ravel’s peculiarities as an artist and a human being.

The story of Russian-born dancer Ida Rubinstein (played by Jeanne Balibar) commissioning a ballet for Ravel is central to the film, while many flashbacks and flash-forwards put his entire life into context. The film shows that the composer himself wanted a new challenge to get noticed by the public and suggested creating something special for the ballerina. The commission followed, the dates of the ballet’s performance were set, but not a single note was written for a long time by procrastinating Ravel. When the work did begin, the rights to Albéniz’s Iberia, the orchestration of which Ravel planned to do for his new ballet, were suddenly bought by someone else. Then, almost out of desperation, the composer first tapped out a new rhythm and then tried out the melody corresponding to it on the keyboard. He dismissed it, but it became too obsessive; it didn’t let him go. He still decided to give it up, but his long-term friend Misia Sert (Doria Tillier), the pianist who, according to the film, was Ravel’s only romantic attachment, suddenly whistled this melody after he sang it to her; she evidently liked it. And then, as the composer confesses to his friend and collaborator, the pianist Marguerite Long (Emmanuelle Devaux), in the film, he decides to simply play this melody, which lasts a minute, seventeen times in succession to fill the needed duration of seventeen minutes. And it does become his obsession; it comes out of everywhere. The rhythm of Bolero begins to be heard in Fontaine’s film in the sound of the composer’s alarm clock, in the impatient tapping of his own fingers, and in the monotonous, rhythmic humming of the factory turbines. It is to this factory that the composer brings Ida Rubinstein to present his creation to her and let her feel its overpowering rhythm.

Ravel, as interpreted by Personas, is a troubled musician, tormenting himself and others, immersed in his own self and searching for the right music for months and even years, tearing up or burning the scores he had been painstakingly composing. At the same time, he is not a hermit, but an active member of Parisian high society (Misia Sert and her brother, the philanthropist Tzipa Godebsky, are his friends and patrons). Ravel passionately conducts his music, angrily comments on rehearsals of Rubinstein’s ballet Bolero, as he is not convinced by its erotic side, and ironically argues with a famous music critic. The line of relations with his mother, shown through flashbacks of letters to her from the front (Ravel volunteered, and it might have been the reason for his future neurological disease), is woven into the image created by Fontaine and Personas of an emotional ascetic who cherishes the women dearest to him (Misia, Marguerite, Ida) and carries them through life because they resembled his mother.

The film convincingly shows the composer’s reservedness, bordering on asceticism and leading critics to reproach him for the mechanistic nature of his creative style. However, the composer, as Fontaine convincingly shows, has his unique emotional world that makes him act unpredictably. Thus, among the most memorable scenes in the film is the flashback with the strange jump from the window of the young Ravel after he had been eliminated from the competition for the prestigious Rome Prize. There is also a strange love declaration to Misia, in which his refusal to kiss her is explained by his desire to differ from other men who all desire her. It is a little peculiar that the film skips Ravel’s work with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and the creation of Daphnis et Chloé, because then it would be clearer why Ida Rubinstein commissioned Ravel for her new ballet afterward.

Fontaine’s Bolero leaves us with the feeling that we have been following the trajectory of an arrow for a long time. It gradually accumulated its energy and suddenly reached its goal, and after that, it was swallowed by the deep sea. Images of the first performance in 1928 of Ravel’s Bolero at the Paris Opera (for some reason the lobby is filmed in the interiors of the Opéra-Comique) become the aural and visual climax of the film, with Ida Rubinstein’s erotically charged performance causing an uproar. In addition to Bolero, a lot of beautiful music (mostly from the composer’s works for piano, as well as from his suites) is heard in the film. But after it, the viewer is left with the aftertaste of a mystery never solved. We are haunted by the sadness of the realization that perhaps Ravel finally never wrote the most important thing that would reflect the essence of his piercing gaze and unusual character. Ravel himself did not consider Bolero the pinnacle of his work, and Fontaine’s film manages to walk a very fine line here. It tells us how one masterpiece was created, but at the same time hints convincingly that many works are the result of chance and coincidence, and perhaps something else could have emerged from the source from which they appeared.