The World as a Playground: Francis Alÿs’s Perspective

At the “Ricochets” exhibition at the Barbican Centre, the rational questions of “why” and “what for,” often tethered to contemporary art practices, are jauntily supplanted by the phenomenon of play—an eternally youthful and invariably captivating pursuit. Through his global journeys, Francis Alÿs has documented children’s games, both centuries-old and those emerging in response to contemporary geopolitical and social shifts, as well as the increasing virtualization of entertainment.

Alÿs, a Belgian artist who has made Mexico his home since the mid-1980s, is renowned for his poetic actions; his repertoire includes traversing city streets in magnetized shoes to collect metal artifacts, propelling an ice block through Mexico City, plunging his head into a tornado in a quest for stability amidst chaos, sending an emissary peacock to the Venice Biennale, and crashing a Lada car into a tree in the Hermitage museum garden as a symbol of the collapse of individual and societal aspirations. Alÿs embodies the spirit of alternative globality, a nomadic flaneur whose urban interventions and guerrilla methods infuse a sense of playfulness into the gravity of the world.

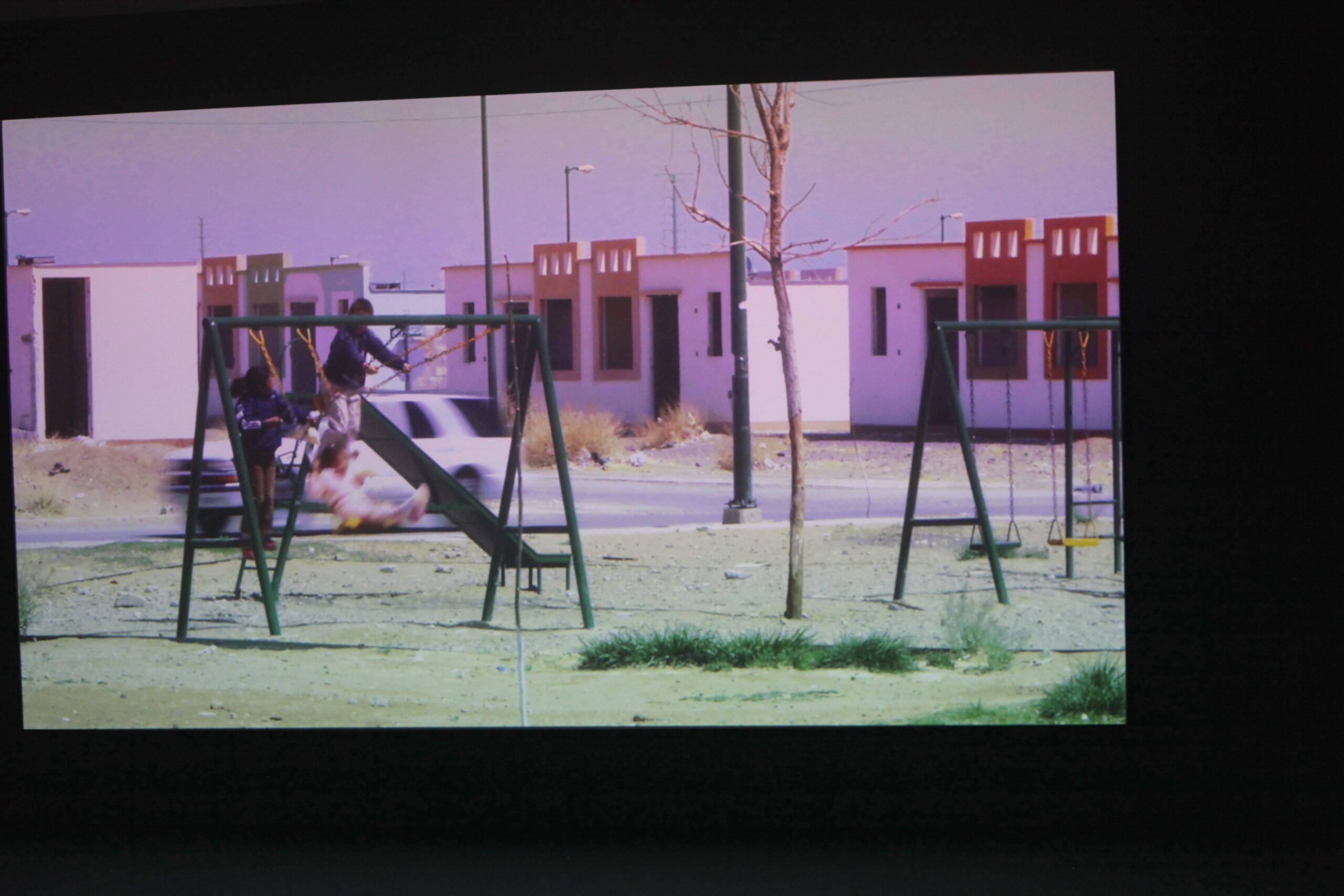

In “Ricochets,” Alÿs presents play as a fundamental human experience, one that children instinctively seek out, unmediated by boring forms of expression, or at the very least, where boredom is minimized to the utmost. The atmosphere of a playground pervades the Barbican Centre’s exhibition hall: screens of various shapes, orientations, and sizes display children at play—alone, in pairs, in groups, with or without spectators. In Nepal, the game involves catching tossed pebbles on the knuckles; in Mexico, the challenge is to secure a seat when the music stops; in Morocco, candy wrappers are slapped with the palm and flipped; in Iraq, an impressive goal is to be scored with an invisible ball. Almost every game displayed is comprehensible without explanations or subtitles (which, in any case, are not provided), embodying practices of participation and similarity, a sense of collective consciousness.

Each video in the exhibition has its own duration, and as they loop, repeat, and blend with others, the soundscape reconfigures the space with every cycle anew—could this also be a kind of game? The interaction between the various projections resembles another form of communication inexpressible in words, one that is between the artist and the viewer, deeply rooted in the tradition of conveying the sacred (art).

Throughout the space, Alÿs’ postcard-sized paintings, created between 1994 and 2024, make unexpected appearances. These works, named after the places where they were painted, predominantly depict children and their vibrant world of entertainments. On the second level of the exhibition hall, Alÿs has compiled an approximate chronology of the evolution of games, complete with brief comments and miniature reproductions of the “playing world” from Bruegel to Diego Rivera. Amidst the extreme fragmentation, in the gestures and movements repeated by children across different countries and various epochs, Alÿs uncovers evidence of the universality and integrity of the world.

In the darkened rooms, minimalist animations are projected, evoking chalk drawings on asphalt—delicate simulacra of innocent amusements: “rock, paper, scissors,” “thumb wars,” and the classic of hide-and-seek. In two halls, finally, viewers are invited to play: to cast shadows on a light panel, to chase vertigo (a reductionist definition given by anthropologist and game researcher Roger Caillois for sport) on low rotating stools.

Since 1999, Francis Alÿs has been collecting children’s games—testimonies to the unity of the world, and conditions of behavior, poised on the borders of art and life until the complex processes of growing up take over. Throughout his career, Alÿs’s primary medium was his own body (chosen ‘due to its constant availability’), however in “Ricochets,” he appears to pass the right of action to the next generation.

The “Ricochets” exhibition at the Barbican Centre will run until September 1.