Vladimir Raevsky: “I’m not ready to discuss the influence of art on the masses”

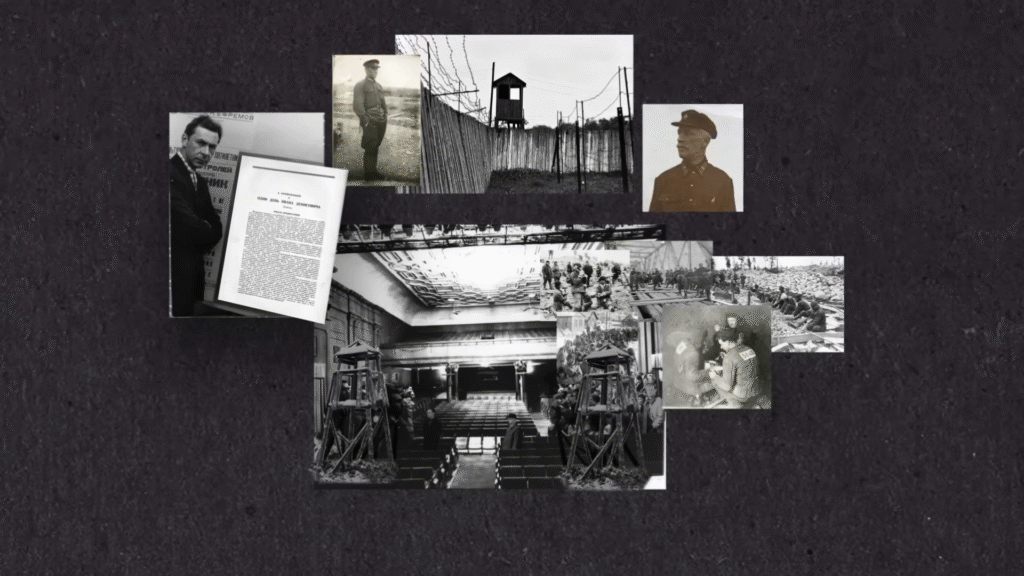

Television journalist, historian, and creator of his own tours, Vladimir Raevsky performs his program “The Realm That Never Smiled” in various cities and countries. Then he returns to London, manages to shoot a memorable segment for his blog, and flies off again—often to joke about a country whose history few are used to joking about. Recently, he also made a film about theatre—specifically, about the history of the Sovremennik Theatre—but it turns out that theatre and performances are just a pretext to talk about something much broader than what’s behind the scenes. That’s where we began our conversation.

Do you remember the first theatre performance that made an impression on you?

I grew up in a theatrical city—Yekaterinburg. Our opera house was founded back in 1912. My grandmother had a friend who worked there, so we’d get in for free. I went to everything, absolutely everything that was staged, sometimes more than once. I especially loved the grand, long operas—like Verdi’s Il Trovatore. I was about nine or ten years old.

What drew a ten-year-old boy to opera?

I still love opera. It seems to me it’s the most unnatural thing you can do—staging operas and singing in them. And I love everything unnatural.

Is history also something unnatural?

Of course. It’s dead, after all. And I love everything museum-ified or archived. Just imagine: an archaic, strange plot where people often behave inexplicably. Like Rigoletto’s daughter being kidnapped when his eyes are covered. Or characters mistaking close relatives in the dark, like in The Marriage of Figaro. And they sing—strangely too, by our everyday standards. I love all that. The more unnatural an opera is, the more I like it—so I’m especially fond of Baroque.

Is drama a more natural art form?

I really don’t know much about theatre, but yes, I think so. Some elements—like the Chekhovian plays, the life on stage that Stanislavski and his colleagues strived for in the early 20th century—feel more natural than opera.

You were invited to make a film about Sovremennik by Ryzhakov, who was artistic director at the time. Would you have explored dramatic theatre if not for the invitation?

Initially, Viktor’s team invited me. But yes, I think I would’ve explored it. The thing is, this film and the story of Sovremennik aren’t really about theatre. They’re grounded in theatre, theatrical relationships, and plays—but really, it’s about something that deeply concerns me: inner freedom, the possibility of that freedom taking root, the ability to exist as a free person in an unfree country, and about this country itself, which always seems to be tightly and inextricably bound to art. That’s what interested me most. Also, the personal dynamics—how these people met and agreed from the start that they’d be equals, that the theatre would be horizontal, with no one “in charge”. Theatre, in this case, is just the entry point for a much bigger conversation.

You said the history of our country is always intertwined with art. Can art save people? Did Sovremennik save its audience—give them something?

No, it didn’t save them. But it changed their lives, slightly, for many.

Gave them a breath of air?

For some, yes. For others, hope. For others still, a chance to find kindred spirits, to feel less alone. I think it’s deeply personal. I’m not ready to discuss the influence of art on the masses—it seems like a dangerous impulse to me. Recently, I went to see Battleship Potemkin at a cinephile theatre in London. I was impressed—but also horrified. I get uneasy when art is meant to influence the masses, direct them somewhere, or change them. Sovremennik, despite its full houses, centred around personal human experience, meant to resonate with the private emotions of each viewer. That’s why we don’t have sweeping mass scenes in the film—the spirit of the era is captured in a small room that changes over 15 years with a young man living in it, leading up to 1956 when the theatre was founded. This personal, intimate space is what matters most to me.

I often hear that if a Russian-speaking artist talks about anything other than pain, guilt, or current events—they’re betraying something: themselves or freedom. Do artists have the right to speak about whatever they want? Must they always view things through the lens of trauma, horror, guilt, and responsibility?

It’s a trap. And we’re stuck in it. On one hand, art can’t be detached from the present—it loses all meaning. Our present has been filled with tragedy and catastrophe for over three years now. So, when that’s not reflected at all, it feels odd. I also find it strange to see artworks that seem ripped from the context of today.

Someone might say, “What about an artist painting flowers? Why should they reflect today’s turmoil?” But even Giorgio Morandi, painting vases and glasses, somehow absorbed his time. So when art is completely divorced from the present, it doesn’t feel like real art to me. But how deeply the present is reflected, how that interaction plays out—that’s a broad spectrum.

On the other hand, placing a strict duty on Russian and Russian-speaking artists to voice certain mantras—this, too, feels wrong. It denies us the chance to be just like any other creator. The further history goes, the less room it leaves for manoeuvre. And it’s not just artists—it’s everyone from Russia. What comes to mind when someone says they’re from Russia? War, death, horror. Or Dostoevsky and Tchaikovsky. You want to be something else, to talk about something else. But again, there’s a sense of inevitability.

A friend of mine, an Iranian who’s lived in London since the ’80s, works in contemporary art and archaeology. But the fate of Iran in the 20th century constantly hangs over him—he can’t escape it. It’s a trap. And honestly, I don’t know how to get out of it.

Only 5–7% of big-city populations go to the theatre. So why has theatre always been such a sensitive space for authorities? From tsarist censorship to Soviet art councils and today’s scrutiny?

Why go after poetry, which even fewer people read and which is harder to grasp? Why kill poets? But that’s how totalitarian regimes work—for decades. I don’t fully understand it myself. But the machinery of terror has its own logic and instincts. It knows what’s incompatible with it.

As for Russian theatre after 2022, it’s hard for me to comment—I haven’t been to it since autumn 2021. It’s one thing to talk about 1935, a time few alive today remember—we deal with documents. That’s the dead history we spoke of earlier. But talking about what’s happening now in my country, which I can’t visit, based only on headlines and hearsay—it feels unfair. I’m not authorised to say.

Why do you think lectures have become so popular since 2022?

There are two reasons—one loftier, one more practical. The loftier: people have been looking for answers since 2022. They want to understand the times, why we all ended up in this part of history’s anatomy. And lectures, whether they’re about the Middle Ages, monkeys, Putin, Zelensky, or political science, help point toward those answers.

The practical reason: people abroad want to stay connected to audiences—and earn fair pay. Lectures are economical to produce—no sets, lighting, filming, or screenwriting. They became a way to speak to the Russian-speaking diaspora while letting that audience support the speakers. I can relate—I’m part of this scene. But I’ve also drifted toward a different bear. I’m not really a lecturer—we’ve turned it into a kind of stand-up.

You once said we’re not used to laughing at our history—it’s treated with deadly seriousness. If we could have laughed at it, might things have turned out differently?

If we could laugh at our history, that would reflect a different kind of society. It couldn’t be the cause—only the result. Or a sign that we’re healthy, open to dialogue, and capable of seeing ourselves from the outside. My goal is to bring together those willing to do that—to see ourselves as characters in a comedy, to run this experiment—not mass-scale, of course!—to start loosening the bolts. But when it comes to the general public, I’m not trying to influence millions.

Do you have a favourite period in history?

“Favourite” is tricky. I enjoy working with material from the interwar years—post-WWI to pre-WWII. But to say it’s my favourite era… Well, sure, I don’t quite “love” 1936, but I absolutely “adore” 1937! [laughs]

Yes, that does sound odd…

It’s that this period is both familiar and distant. We have lots of photos, films, and grandparents who lived then—it feels accessible. But WWII cut it off from the better-known ’60s and ’70s. So it feels both forgotten and imaginable. I love the painting, architecture, and literature of that era.

Why were Art Nouveau and Art Deco so under-represented in Russia?

Art Nouveau flourished—just under the name Modern here. Riga calls it Jugendstil. Art Deco—yes, we didn’t get much of it. There are exceptions—like Moscow’s Aeroport metro station, which is very Deco. But broadly, no. I’ll say something unpopular here: I think Art Deco came from capitalism. It was linked to private initiative, capital, and investment—a response from art to the wealth of the few. But the Soviet Union went a different way.

When you moved to London, did you find places that gave you strength or that you fell in love with?

Absolutely. I live in my favourite neighbourhood—Hackney. I love it dearly. Some days I don’t even leave it. It’s incredibly international, very immigrant-heavy, and historically one of the poorest areas. I greet my barber in Turkish, the lady who sells fruit in Arabic. My favourite cafés are here. A 15th-century tower, the imperial Hackney Empire Theatre from the early 20th century. An old cemetery, a Victorian park called Victoria, and a great little museum. My favourite thing about London is my neighbourhood.

When you fly in from a lecture, do you feel like you’re coming home?

Oh, yes. This is the first city I’ve ever missed when away, the first place I don’t want to leave. Sure, I enjoy travelling—Oslo, Malta—but I have very tender feelings for London, and Hackney especially. I got very, very lucky. I know not everyone feels this way, but I truly feel I’m coming home.

Did that feeling come right away?

Pretty quickly. I moved here in the third year of the war. During that time, I lost my first home—Moscow—and Russia altogether. Then I found a second home: I lived in Tel Aviv for almost two years. Then came London. Moscow is a city I know inside out. Yekaterinburg is my hometown—I’ll always miss it. Tel Aviv also became “mine”, and I’ll always be a proud Israeli.

And London? Who am I here? Nobody. Hundreds like me arrive daily. I’m nobody here—but somehow, this strange place has become the most interesting, the most magnetic. That’s how it turned out for me. I feel lucky. Really lucky.