What Grief! About Love and Azovstal

Director and playwright John Retallack staged “Mariupol”, a play by Katya Haddad, at The Cockpit theater with the support of the David Nott Foundation. This is the first staging of the play after a successful reading at Oxford’s The Old Fire Station.

The set consists of just a few chairs and a couple of lamps. Later, details of wartime life are added—a few crates, a helmet, a flask, and a mug—the action, after all, partly takes place in the basements of Azovstal. But this minimalism is not forced; rather, nothing more is needed. Additionally, the atmosphere is created by a projector, which alternates between casting images of sea waves and terrifying footage of ruins onto the stage floor.

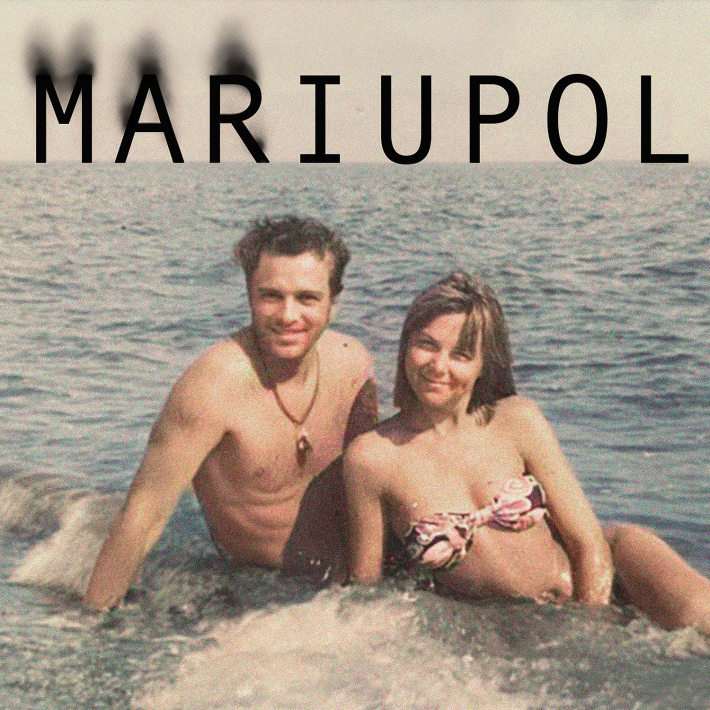

Haddad wrote the play based on her own memories of summer in Mariupol in the early ’90s. The poster features an old photograph from her personal album. The sea, a couple, smiles. Writing from personal experience, through one’s own prism of feelings, is always risky—the text can become so personal that it fails to detach from the author and take on a life of its own. But “Mariupol” navigates this reef effortlessly. On the contrary, in some incredible way, the performance begins to unpack the audience’s own memories.

It is completely unknown how these English actors managed to perform a play, partially set in post-Soviet realities, as if they had experienced them firsthand. If “The Cockpit” has a time machine, give me a sign—I have something to check! Otherwise, how else could they possibly convey a train station farewell so vividly that you can almost smell the specific scent of creosote, fried pastries, and longing?

The characters of Galina (Natalie Barclay) and Steve (Oliver Gomm) are portrayed with astonishing accuracy and evolve throughout the performance. They are not just alive but develop from scene to scene. And the actors grow along with their characters—or rather, they age, not from the passing years but from grief.

We won’t spoil the plot (though we don’t go to the theater for plot twists, do we?).

At the very beginning, Galina’s summer dress is so light, so playful, and suits her so well that she suddenly becomes shy—her cheeks flush in the middle of a conversation, and—miraculously—she suddenly resembles the main heroine of a Soviet film, Natalya Varley in “Kidnapping, Caucasian Style”. A student, an achiever from Moscow — though certainly not a Komsomol member. Young, carefree, glowing from within like a light bulb.

And beside her—Steve. That dashing demeanor, that half-smile acting as a shield for his true emotions, those eyes, shaded by his lashes like the visor of a navy cap. Steve is not his real name; it’s a nickname, a pseudonym that stuck to naval officer Bondarenko due to his love for Stevie Wonder’s songs. But no one calls him anything else.

The scenes in Mariupol are like snapshots from the very poster. Click—they’re sitting on a bench by the embankment. Click—a suitcase just before Galina leaves for Moscow (Steve stays in his native Mariupol.). Click—a hospital in Moscow. Click—Mariupol again. This time, in ruins.

The play takes us through three time periods: from carefree 1992, through 2002—mature, difficult, tragic—and finally arriving at 2022—monstrously, unbearably terrifying.

But really, it is terrifying almost from the very beginning, from the moment the young student carefreely jumps into the sea. The sense of boundless grief washes over the audience again and again, like a rising tide, each time stronger. There is no defense. The audience sits on four sides, while in the center, on a small square platform, the actors perform. The venue is tiny, the actors—practically right in front of you. And it seems this is a play about grief.

Barclay and Gomm perform not with theatrical, but human intonations—so naturally and intimately, without distancing themselves from their characters but merging with them, dissolving, transforming completely.

In such conditions, it would be easy to slip into hysteria, pathos, or excessive emotion. But they never allow themselves to push their emotions too far; they always perform quietly, without shouting. Even when speaking of death. Even when in mortal danger. Even when bombs explode with a deafening roar—Galina sobs uncontrollably but clamps her own mouth shut.

There, in the bunker of the shelled factory, Steve finally looks at her—truly looks at her—with eyes that no longer smile. And in them, there is love.

“Mariupol” is not a play about grief. No. It is a play about love, surrounded by grief.

The recent trend of interactivity in performances related to Russia and war is left aside here. The audience is not addressed, not forced to speak or chant. A wall is built between the stage and the hall (four walls, actually, on all sides of the room). The actors, illuminated by stage lights, are like fish in an aquarium—you cannot reach them. And yet, under these conditions, you feel compelled to say out loud: “What grief!”

Life granted these two only three meetings, but far more grief. And so it is. But love proves stronger. And in the end, Mariupol is not a political statement, nor even an attempt to comprehend today’s history. It is an ode to love—love that always lingers, love that flares up again in the weary, frightened Galina, just as it did thirty years ago. And there, in the underground depths of the factory, stands that very same light bulb—and Steve looks at it, and despite the surrounding horror, from them radiates happiness.

“Life has once again defeated death in a way unknown to me,” wrote Daniil Kharms in his absurdist text.

In “Mariupol”, love conquers all.

That very same love—merciful, unwavering.