“Winter in March”: A Puppet Animadoc about Escaping Russia Competes at Cannes

The new film by Natalia Mirzoyan, Winter in March, will premiere in the La Cinef competition at the Cannes Film Festival. Once known as one of the leading figures in Russian animation, Natalia Mirzoyan now represents Estonia and Armenia, and her new puppet film centers on the story of a Russian emigrant couple who left the country in March 2022. In an interview, Natalia talks about how the story of migration turned into a road movie, and how textiles and cotton became symbols of lost hope.

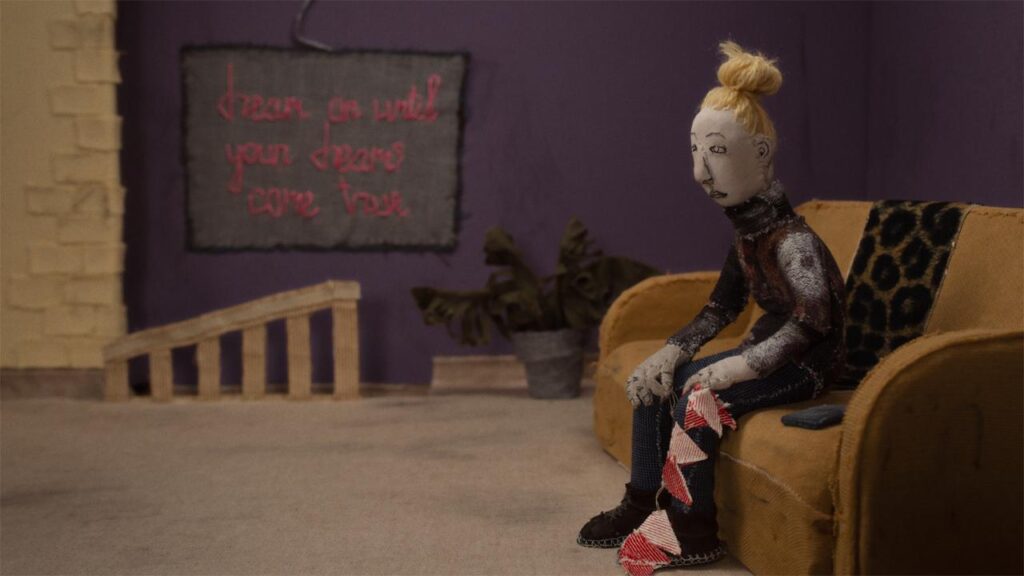

Two rag dolls walk, sinking their feet into cotton; colorless figures shout “Stop the war!”; snow falls on soldiers’ helmets; cars line up in an endless queue on a mountain road… — these are shots from Natalia Mirzoyan’s short puppet film Winter in March, which tells the story of two young Russians, Kirill and Dasha, who flee from Russia to Georgia after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine begins. Shot at the Estonian Academy of Arts (EKA), Winter in March will have its world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, where it will represent Estonia and Armenia in the La Cinef competition.

The creator of this puppet work, director Natalia Mirzoyan, is well-known to both festival and general audiences: six authorial animated films that won awards at major animation festivals, plus two dozen episodes of the iconic Russian series Kikoriki… a truly unique career.

An Armenian by origin, Natasha was born in Yerevan. She moved to Russia (to St. Petersburg) at the age of 22 to study easel painting. While looking for a job, she ended up at the Petersburg studio and stayed there for many years. Her debut film was the poetic coming-of-age story My Childhood Mystery Tree (2008), followed by Chinti (2011), which brought her widespread recognition. A provocative biblical anecdote Madame and the Maiden, the charming children’s mini-series The Kingdom M, the raucous Merry Grandmas!, and finally the watercolor seven-minute piece Five Minutes to Sea—a tiny, translucent, atmospheric film that enchanted animation festivals around the world… Few directors can boast such a diverse, multifaceted, and astonishing filmography.

And now, a very serious, sad, political, and, against all expectations, a puppet film made in Estonia with Armenian financial support. And immediately, a Cannes competition—a rare, almost unprecedented success for animated films, which only a few are honored with each year.

Natasha’s Facebook post announcing this incredible achievement sounded almost apologetic: “To be honest, I doubted whether it was appropriate to release it at festivals now, while Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continues. I often feel like disappearing when I read the news—not talking about our experiences or emotions. But the world is so shaky now, and we decided to send a working version of the film to Cannes. The selection encouraged to finally finish the film after 2.5 years of work just in 2 months.”

The story of Dasha and Kirill, which became the basis for the film, is so typical that it feels almost collective. News of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, hopeless protests followed by mass arrests, the escape through Upper Lars to Georgia. Horror, the “desire to freeze and not move,” the feeling of losing the right to live, helplessness, shame, guilt, fear…

MT: Natasha, why did you choose this story?

NM: Before the invasion, I lived in Armenia for six months. And suddenly, my Russian friends started coming to my Armenian universe. It was all very surreal. Everyone was shattered. Depressed. Afraid. In despair. You know, in that self-devouring state. And it seemed important to me to record what we were talking about. I did 7–8 interviews with different people. And I spoke with Kirill already in Georgia. His story was full of cinematic imagery. For example, I really liked the image of snow on soldiers’ helmets. Helmets covered with snow—that was the first image that hooked me. As you know, many directors (myself included) often start films from a single image.

Then I interviewed Dasha—Kirill’s wife. At first, I wanted to make a sketch from different stories, but then I thought that if I immersed myself in one story, it would be deeper and more interesting than if I showed a mosaic.

Moreover, this story turned out to be very universal. As a rule, in emigration, men behave exactly like Kirill does. And women—exactly like Dasha does.

MT: So it all started with Kirill? But only Dasha remains in the film.

NM: Yes. I had many interviews with them—about 6 hours in total. And the script was written from the perspective of both characters. But literally at the last moment, I decided to throw out all of Kirill’s text and make the story from the woman’s perspective. Maybe because I am a woman myself. As a result, of the 16 minutes of the film, the text is heard for at most 4–5 minutes. And only a woman’s voice.

When talking about the film, Natasha calls Winter in March a road movie. But perhaps the term odyssey would be more fitting. Or even an anti-odyssey. After all, the famous Greek hero returned home, while the characters of this small puppet film, on the contrary, flee from home. An Odyssey of the 20th–21st centuries: a story of escape, exile, a journey into the unknown.

And the choice of technique and materials makes the theme even more poignant: everything takes on a second layer, a subtext, becoming symbolic. People who have no control over anything and cannot change anything turn into limp rag dolls. Rough stitches on their hands and faces look like scars. The snow made of cotton that engulfs the main heroine is associated with the political “cotton” (a term inspired by the word ‘vatnik,’ which signifies conformist and uncritical loyalty to the state). And the cardboard world, once so reliable and solid, folds and collapses before our eyes, revealing its fragility.

MT: Why puppets? You hadn’t worked with puppets before…

NM: I applied to EKA [Estonian Academy of Arts] before the Invasion. And Ülo Pikkov [Estonian animator, director, producer, professor, and head of the animation department at EKA] asked me at the interview: “What are you planning to do here? I know your films, you have tons of awards, why do you even need EKA?” And I said that I dreamed of trying myself in puppet animation. I really had dreamed of it since I was 20, but there was no opportunity in St. Petersburg. So I went to EKA with the goal of making a puppet film.

But when I decided to do this story, it became clear that doing it with puppets was pure madness. It’s a road movie, tons of sets, tons of shots. In the end, part of the sets is flat, part embroidered, part are puppets. I made all the puppets myself—about eight of them. Plus, I was very lucky with my co-author, Sander Põldsaar: he built the sets, was the cameraman, and later did the sound. And he invented absolutely incredible constructions. I have the mindset of a drawn-animation director. So I wanted to do transformations and other unusual things for puppet cinema, and he figured out how to bring my fantastic ideas to life.

Winter in March is indeed made very inventively. Trying to convey the characters’ emotions and inner worlds, Natasha came up with many images and visual metaphors. A heroine walking barefoot through the snow, fabric houses tearing apart, a character collapsing like a rag on the floor, tied hands… But perhaps the most amazing thing in the film is not even that, but that the puppets seem truly alive. And despite the stylized visuals, they are perceived as real people.

MT: What’s the secret? I feel like there’s some kind of trick here…

NM: In puppet animation, minimalist animation is often used. The puppet changes position —stop, changes position—stop. But we added breathing to every frame and constantly moved the camera. Plus, for many scenes, we filmed ourselves on a phone and then mimicked the movements.

And even this phrase about filming themselves on the phone to capture the authenticity of the characters’ movements sounds metaphorical. It’s quite a common practice in animation, but it’s hard not to think that Winter in March is also about Natasha herself.

MT: How did you leave Russia? How did you end up in Estonia?

NM: I first planned to go to Estonia about 11 years ago. But then I started a project called Marika (that’s my daughter). Then I planned again, but COVID began. After COVID, I finally decided and applied. That was before the invasion.

It so happened that I lived in Armenia for about six months during that period. And on February 15th, we went to St. Petersburg to pick up documents, collect our things, and head to Estonia. Everything was already at the breaking point, but we still didn’t believe the war would actually start, so on February 15th, we arrived in St. Petersburg. And then the Invasion began.

Lyoshka [Alexey Bazhin—co-founder of Inoekino, Natasha’s husband] went to a couple of protests. I didn’t because Stepa [Natasha’s son] was only seven months old.

At EKA, where I originally applied with a Russian passport, they told me I wouldn’t be accepted with it anymore, so on March 8th, we flew back to Yerevan to get Armenian passports. I had citizenship, but my passport was expired.

And then we moved to Estonia. With just one suitcase.

Unlike The Odyssey, refugee stories usually lack a clear ending. And although the characters of Winter in March successfully leave the country and find new places to live, it’s unclear whether these countries will become their permanent home.

Similarly, Natasha and her family’s personal road movie is far from a happy ending. Some time ago, Natasha received a five-year residence permit in Estonia. But her husband, Alexey Bazhin, has so far been denied residency. Although he continues to try to get that coveted document that every immigrant dreams of, the chances are shrinking by the day, and the family understands they might have to move again.

When the conversation turns to her own story, Natasha grows sad and recalls something she read recently about Lotte Reiniger. This great director began her career in Germany in the 1920s. In 1926, a full 11 years (!) before Disney’s Snow White, she almost single-handedly, in her unique silhouette animation technique, created the first full-length animated film in Europe—The Adventures of Prince Achmed. With Hitler’s rise to power, Reiniger, who was involved in “leftist” politics, decided to leave the country. However, not a single state was willing to grant her permanent residence…

“She lived her whole life between countries. She always had visa problems. She drifted from place to place,” Natasha finishes her thought. “And now, many of us are the same. For many of us, the road movie is still going on.”

Exclusive works by Natalia Mirzoyan are available for purchase in the “Art” section of our online-shop.