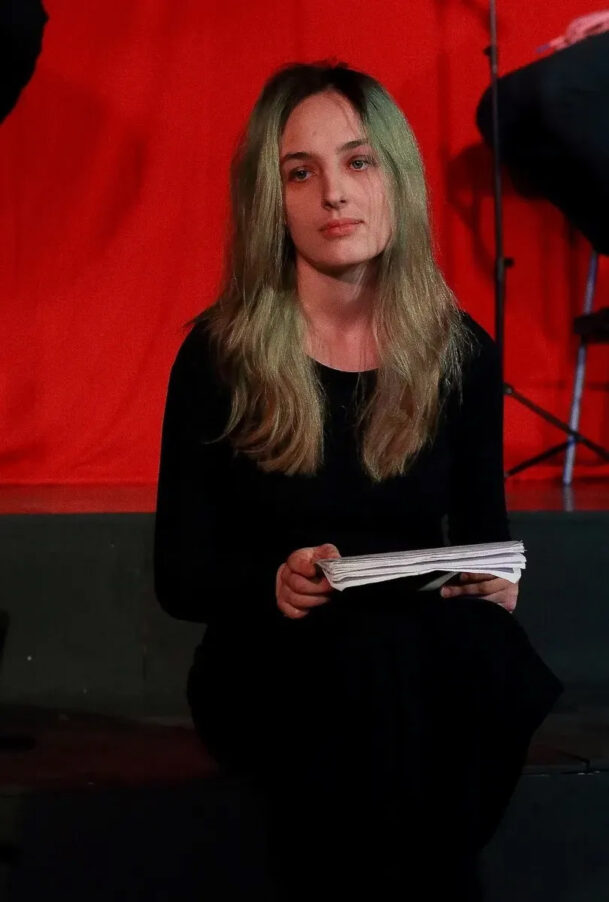

Yelena Kostyuchenko is a Russian journalist, writer, LGBTQ+ activist, author of the book My Beloved Country, and playwright. We met with Yelena before the performance of Unseen by Ia Patarkatsishvili, which Kostyuchenko flew in to see—and to discuss afterward. Yelena is not only a fantastically courageous journalist but also a person deeply connected to theater. She is the author of the verbatim play New Antigone, staged by Yelena Gremina in 2018. We talked about theater—and how art can help during the most challenging times.

Yelena Kostyuchenko: “Love Does Not Demand Submission”

I think it’s very important to stage performances like Unseen today.

Before flying to London, I read everything I could find about it. And, of course, it’s a conversation about political prisoners. Because their situation is not improving—it’s deteriorating progressively every second. I am corresponding with several of them, and some have been imprisoned for ten years already. That is, these are people who were jailed back during the Bolotnaya case. Among those I correspond with, there are doctors, workers, and a young female artist who had just turned 18.

One of the characters in Unseen is a doctor!

And in this context, of course, I can’t help but think about Nadezhda Buyanova and how she will endure imprisonment. She is my mother’s age and type, and when she gave her last word—when she said she had simply wanted to heal people and nothing more—I couldn’t stop crying. Naturally, I imagine my mom in her place. My mother is still in Russia, as is my younger sister, and of course, they both face enormous risks every day.

What do you think? Today, does art, including theater, have the right to talk about anything other than this pain?

I don’t know. It seems to me that art and rights exist in different dimensions. We talk about pain not because we have the right, but because it’s impossible to remain silent about it. At some point, you just break open, and then art comes to the rescue, giving us language.

I studied under Mikhail Ugarov and Yelena Gremina when they were alive. And they believed that art neither had the right nor should talk about anything other than repression and war, as long as repression and war exist. Precisely because the greatest amount of pain, trauma, horror, and instability is concentrated in that place. That’s what their Teatr.DOC was all about. Mikhail Yuryevich Ugarov used to say he didn’t see the point in staging The Three Sisters right now. Teatr.DOCstill adheres to this principle while remaining in Russia. Many have left, but many stay and work underground. And this is absolutely incredible.

Naturally, I immediately think of your play New Antigone.

It was very painful to watch—and you invited the women from the Beslan case to the performance. Do you remember how you felt?

Well, of course, when I performed—or rather, no, it wasn’t a performance but a documentary play about the trial of six Beslan women, whose children, husbands, and other loved ones died during the school siege. They had come out onto the street wearing T-shirts that said, “Putin is Beslan’s executioner,” and were condemned for it.

When they were in the hall, I felt an enormous responsibility before them. I understood that when you speak about someone else’s pain, it’s very easy to make mistakes, even in tone. And tonal mistakes, for some reason, are the most unbearable in such circumstances. The audience will never forgive them, and neither will those who have experienced it themselves. You can’t pile on pathos where a person has a raw wound, for instance.

When they stepped onto the stage, I saw that the audience was deeply hurt, and some found no better way to deal with their pain than to lash out at these women.

I remember one man—his inner fire was visible—stood in the middle of the hall and said, “Where were your men when the cops dragged you, beat you?” And Emma Tagaeva replied, “My men are dead. My husband and two sons were killed. I have no one; I’m alone.”

Without a doubt, theater is an important medium. I didn’t understand theater’s power until I started working on New Antigone. When I was in the courtroom, what troubled me most was the thought that no one would believe me—because it’s impossible to grasp that these women were being judged. I had a recorder with me, which a bailiff constantly tried to confiscate. He sat behind me and, whenever I relaxed my grip, tried to snatch it. To prevent the city from gathering and rescuing these women, all the doors were locked within ten minutes of everyone entering the courtroom. Throughout the session, people stood outside, banging on these locked doors.

When Yelena Gremina suggested creating a play about it, I didn’t immediately understand or accept the idea. Why a play? What’s the point? Only when we began reading the script did I suddenly feel like I was back in that courtroom—feeling the bailiff behind me, the hard wooden bench, the women breaking bread to eat, as no one fed them, of course. I saw the bruises on their hands.

Only then did I understand how theater works—it makes everyone in the audience a witness. You can no longer deny this piece of reality, nor say it didn’t happen.

Yes, they can lock every door on Earth, but if theater manages to bring truth, pain, life, and death to the stage, then these people will no longer be alone. The audience becomes witnesses—linked by an invisible but very strong bond. If art and journalism have any higher purpose, it is precisely this.

I don’t believe we’re the fourth estate or that art serves the people. Art serves only itself. But if we speak of a higher purpose, I believe it lies in creating these invisible connections between people, which are the strongest things in the world, holding it together against chaos—not politics, the UN, or borders. I’ve become convinced of this over the past three years. I’d like these connections to grow stronger and more numerous.

Is this love?

I think so. Love in its purest sense. The kind that is patient, kind, does not envy, does not boast, and is not proud.

Your book My Beloved Country is filled with love. With all your life and professional experience, how have you managed to preserve love?

I don’t think love is something you can preserve or beg for. I am a believer, and I truly think that love is simply a gift from God. There’s no other way to explain why we have it.

Can it be lost?

I think so. You can reject it, especially because sometimes loving is very painful. My love for my country is a very, very painful feeling right now. It brings a great deal of pain into my life. But I’m not ready to abandon it precisely because I understand the nature of this feeling.

Love doesn’t demand submission, killings, lies, silence, or fear. Love demands a very close look at what you love and care for the fate of what you love. That’s love.

And my life experience has indeed been, let’s say, varied. But I have seen how love can triumph over death: for example, in Zaporizhzhia in the spring of 2022, when I was preparing to go to Mariupol. There were very active battles, and no humanitarian corridors existed. But people got into cars, tied them with white rags, believing that no one would shoot at civilians, and formed columns, heading to Mariupol in the hope of finding and saving their loved ones. There were thousands of these people—the column had no end. They believed their love would save those left in the city. I witnessed this and will never forget it. That’s why I will never betray my love, no matter how much pain it brings me.

Sophocles’ Antigone is an ancient play, written centuries before Christianity. But New Antigone is an entirely Christian play. Not coincidentally, you quote the New Testament. What can you say about hatred?

I don’t think love and hatred are opposites. It seems to me that the opposite of love is indifference. Hatred, probably, is a very strong, destructive process that sometimes begins within and then seeks an object. First, you feel this emotion inside, and then you look for someone or something to direct it at. And then you’re told where to aim it.

How do you deal with it?

Poet Lev Rubinstein once said something profound: hatred is more fundamental than its object. Approach someone who hates another and start asking them questions, and you’ll find out that they don’t hate just one specific group of people but many. I think hatred is like an autoimmune disease of the soul. I’ve seen how hatred consumes a person alive, leaving only an empty shell. That’s why I try very hard not to cultivate it in myself.

I often notice that when I begin to feel angry at someone, it’s connected to my own inner dishonesty. For example, it hurts, but I don’t want to admit it. Or I’ve made a mistake, but I can’t accept that—I’m supposed to be perfect!

I mentioned earlier that I correspond with political prisoners. What struck me in their letters is the complete absence of hatred—it simply doesn’t exist as a dimension. It’s assumed that we, on the outside, should support political prisoners. But in reality, it often turns out that they support me in their letters. A friend of mine is currently in solitary confinement, where there’s nothing but a wooden bench, a barred dirty window letting in cold air but no view, and a hole in the floor for a toilet. She writes: How can I find joy in today?

In solitary confinement, you’re not allowed anything—not a pen, not a notebook. You’re supposed to sit and reflect on your behavior. And then, she writes, I remembered how I used to compose poetry in my head during school lessons. It’s such great practice! And when the guards come to taunt her, saying, How are you? What’s new? she smiles and says, I’m fine. Everything is great!

How would you describe your current state?

I haven’t found the right word in Russian to describe it yet. In English, there’s the word exile, but in Russian, изгнание(exile) sounds overly dramatic.

Ah, standing on a little pedestal, “I’m in exile.” And it’s not refugee either because that immediately makes me think of Ukrainian refugees who literally fled under bombs. I ran under bombs for work and was paid for it. It’s not emigrationeither—emigration is voluntary, and I never wanted to live abroad.

Sometimes I feel helpless: I’m 37 years old, and what now—rebuild my life from scratch? But when I correspond with political prisoners, and they share how, in a two-meter solitary cell, they manage to feel free, creative, productive, and engaged, I realize I can do so much. I’ve even started writing my second book.

If I may, I would like to tell your readers: please write to political prisoners. There are many of them, and their numbers grow every day. These are people who most need your attention, sympathy, and warmth. But you also need their survival strategies, which they practice every day. That invisible connection is the strongest bond in the world.