You Won’t Get Me! Alexander Molochnikov stages Seagull: True Story

The play Seagull: True Story ran with great success in New York, and now Molochnikov has brought it to London. The premiere at the Marylebone Theatre played to a full house and—astonishing for London—to ovations so long the curtain rose five times. And it really is a very good production and a very good play (spoiler: not Chekhov’s).

In Seagull: True Story there are countless directorial and spatial inventions. They’re strung like beads along the thread of the narrative, exquisitely precise and devilishly witty. To describe them would be thankless—they must be seen. The production also looks almost annoyingly rich: a grand, intelligent set. And then the realization dawns that all this magnificence is made from red velvet, cardboard, plastic bags, and yellow tape—and that revelation makes it even more impressive.

It is, above all, a very young play. It radiates such vitality, such life-force, that it seems to push the despairing protagonist away from the suicide that Chekhov would have demanded—but Molochnikov does not.

But let’s take it step by step. Of course, this is not Chekhov’s Seagull—Eli Rarey’s script is partly based on Molochnikov’s own work at the Moscow Art Theatre, and partly on his emigration to the United States. The plot: a young director stages The Seagull at the Moscow Art Theatre, the war begins, he emigrates, and stages The Seagull again in America.

The production is, first and foremost, an artistic statement about theatre and about the fate of the director—Kon (played by Daniel Boyd). It is not about war (damn it), not about tyranny, not about escape—it is about a theatre director, his life, his work, his love of the backstage corridors of the Moscow Art Theatre, his actress mother. And only then is it about war. About that terrible 24 February morning during rehearsals at the Art Theatre, which crashed down on the actors’ heads—so quietly, so domestically. And that ticket to New York… Kon packs his suitcase, changing out of a loose Russian shirt into a shabby zip-up tracksuit that completely alters his body: the energetic, vivid man is suddenly hunched and constrained.

The surrounding darkness tries casually to grind this little director into mince—not because it wants to, but because the meat-grinder doesn’t care whose flesh it turns into cutlets. If not Kon, then his friend Anton (Elan Zafir). Yes, there’s a political message here, but it’s cleverly hidden, read between the lines. This is not a pamphlet, but a drama of a personality.

And that’s exactly what makes Seagull: True Story a genuine artistic statement about the current war—a statement full of rage, despair, and… love of life. That, at least, is pure Chekhov: so much love (and how nervy it is!), only instead of a magic lake there is a white bathtub on baroque legs.

The acting is precise to the last gesture and glance. Ingeborga Dapkūnaitė plays Olga’s maternal jealousy with a barely perceptible movement of the lips. Everyone admires her artistry—colleagues, managers—but her most important scene she plays alone, in her dressing room, after switching off a video call with her son. Dapkūnaitė is dazzlingly good—slender, elegant, on sharp heels, like a silver hairpin—and just as dazzlingly terrible, for beneath the prima’s beauty lies not a tender mother but a selfish monster-Arkadina.

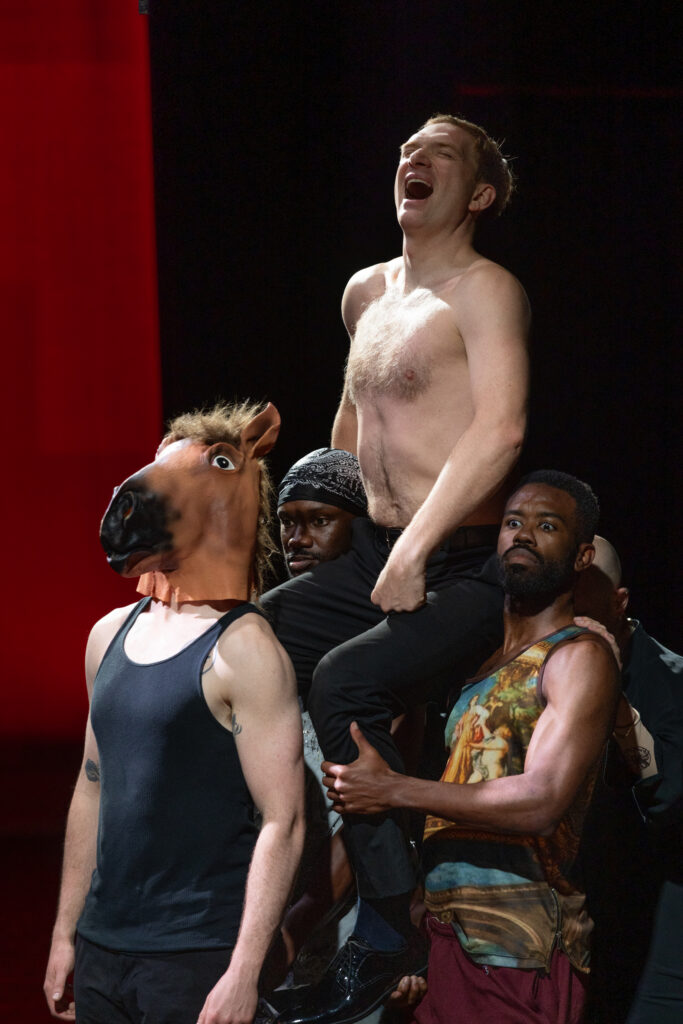

Andrei Burkovsky plays two theatre managers—one in Moscow, one in New York. At first glance, this suggests some kinship between them, but in truth they share nothing but a profession. A huge, many-layered, complex role! Burkovsky manages to talk with the audience, quietly discipline the actors, play his role, and engage in a love triangle. He changes faces, jackets—these endless transformations have something devilish in them. No wonder he appears in Kon’s dream as an equestrian statue of a tyrant-ruler.

One of the most striking performances is Elan Zafir’s double role as Anton and Sorry. His Anton—the assistant director, Kon’s friend and comrade—is gentle, quiet. He wears his jacket and scarf, speaks softly, nothing suggesting the tragic fate awaiting him when he confronts terrifying forces. You can picture him sitting aside, humming some little tune to himself his whole life. And then—suddenly—he throws himself into the meat-grinder. He gives Kon a birthday present: a solitary fish in an aquarium, a symbol of muteness and loneliness. A standard that applies to so many here. Who is the actor without English in an English-speaking country? Who cannot, for various reasons, say all they wish to? The fish in the aquarium. Incidentally, also named Anton.

There’s another layer—intentional or accidental—of references to Moscow theatre life. Burkovsky’s character spreads his arms like wings against the red curtain, and suddenly the crimson is replaced in your mind by the olive-grey drape with its flying seagull. The Moscow Art Theatre, of course. Strange flashbacks: Boyd truly resembles Molochnikov, but at times he seems identical to other Moscow actors, as if souls had migrated. And Dapkūnaitė sometimes recalls different actresses from the Art Theatre—both uncanny and funny, almost magical. Or Kon and Anton walking from the Art Theatre to Red Square: Kamergersky Lane, the Theatre School, Chekhov’s statue, the turn to Tverskaya, the underpass. This is not nostalgia—it is literally the power of theatre.

The play is divided into two acts—Moscow and New York. And by the ease with which Kon joins a rehearsal in New York, it’s clear: the language of art is universal. Art, but not communication. How funny when one American actor yells indignantly: “Don’t touch me! Why are you touching me?” The audience roars—the gag lands perfectly. Kon, seeking total freedom of expression, flies to New York. Quite literally flies—pressed into his seat, hoping at last to merge with the American dream. But there too disappointment awaits him—and the more unexpected, the more painful.

The breakneck rhythm of the play (you barely have time to breathe in either act) is built on the interplay of tragic and comic, fear and freedom, jealousy and love. Yes, there is a love story too. Stella Baker plays both an actress in the Moscow troupe and the American Nico—the main lyrical heroine. This Nico is stunningly beautiful, glowing with the same vitality that suffuses the production. A suave patron makes advances, but she knows what she wants:

“You keep looking back, always looking back. How long can you keep looking back? I’m not Nina, I’m Nico! The Seagull, The Seagull, The Seagull—you offered me a Seagull, but he offered me a child!”

She almost—but not quite—cries. She holds back with furious restraint, and only at “I truly loved you!” does her voice break.

When life turns tragic, people often feel they are no longer themselves. A beast in a trap, a bird in a snare—but not themselves. And—whether for good or ill—only they themselves can decide how much strength they have to resist the unstoppable destructive force that wants to devour everything alive.

The edge of the platform. Kon’s tear-stained face.

The wind of the arriving train.

A step—forward or back?

No vials of ether.

You won’t get me.