New Year

To celebrate the New Year twenty-four times in a row, one would need to remain just west of the “midnight line” at all times and move along with it at the speed of the Earth’s rotation. At the equator this speed is approximately 1,700 kilometres per hour — still an unattainable threshold for civil aviation — but at London’s latitude the task becomes entirely feasible. On the condition, of course, that one has half a million dollars to charter a Gulfstream G700 business jet — perfectly suited to this chronologically deranged undertaking.

An irrational madness of the same order as the New Year itself. This is the only mass ritual on the planet in which humanity invents an illusory point of renewal while fully understanding that no renewal will actually occur. The morning of the first of January differs from hundreds of others in the year only by a brutal hangover — and not even that for some. And yet the New Year is our cultural way of convincing ourselves that time is not an abyss, that it does not own us entirely. Sometimes we may even catch it by the tail, just long enough to make a wish. And although this holiday may seem trivial — hardly something where one would expect to find depth — it is precisely here, in humanity’s simplest habits, that ancient mechanisms are concealed, mechanisms that have outlived empires, religions, and calendar reforms.

In the second millennium BCE, Mesopotamia celebrated a festival known as Akitu, rooted in the Babylonian myth of creation. Once a year, in spring, priests recited it aloud: the god Marduk battled the goddess Tiamat, the monster of Chaos. Naturally, he prevailed, fashioned a new world from her shattered body, established the cosmos in correct proportions, and populated it with humans so they would help the gods maintain order. The central piece of this multi-day rite was the ritual humiliation and symbolic nullification of the king (sadly, the tradition did not withstand the test of time). During the ceremony, the ruler was stripped of his insignia of power; priests could strike him across the face; and he, in turn, was required to confess that he had failed to fulfil all his duties. Only then was the king forgiven and once again deemed worthy to rule. No politics — pure cosmology: until the king was reset, the world itself could not be renewed. Babylon began the new year “with a clean slate” along the entire vertical of its hierarchy.

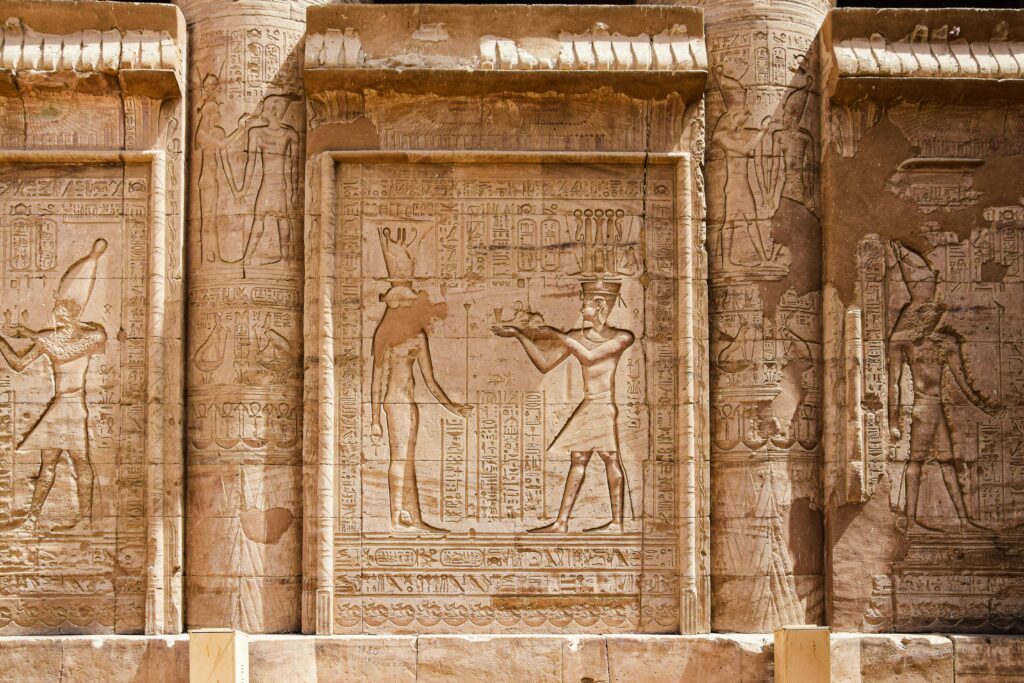

In Ancient Egypt, the New Year was called Wepet-Renpet — literally, “The Opening of the Year”. It fell on a summer day when Sirius first appeared in the sky for a few minutes before dawn. At the same time, the Nile began to flood — a symbol of renewal — and the first month, Thoth, commenced. The veneration of the rising of Sothis dates back to the pre-dynastic period, and unlike the Sumerians, this was not about a cosmogonic battle but about the return of Ma’at — the principle of order, correctness, and harmony — through a natural cycle. Wepet-Renpet was not a staged drama but a ritual of calibration. The Egyptians did not conquer chaos; they simply waited for it to recede.

The third New Year model was the Roman Saturnalia. Celebrated in December, its essence lay in the temporary abolition of the world as such. Slaves reclined at tables as free men, while masters served them food; mockery of authority was permitted; customary restraint vanished. Courts did not sit, schools were closed, and state affairs came to a halt. Does this sound familiar? Indeed, it was Saturnalia that endowed the modern New Year with its greatest number of archetypes and behavioural patterns. The temporary suspension of rules, social inversion, the tradition of gift-giving and communal celebration — all originate there. When December’s chaos came to an end, camethe Calends of January — the first days of the month dedicated to the two-faced god Janus. One face of the deity looked to the past, the other to the future, making clear that time neither begins nor ends; it merely turns its head and restores the world to its customary structure.

Somewhat later — around the third century CE — a key festival emerged between Saturnalia and the Calends, occupying the place of the winter solstice: the cult of Sol Invictus, the Unconquered Sun. Under Emperor Aurelian, it became a public holiday and was celebrated as the return of light after the longest night. Unsurprisingly, Christianity, recognising the futility of uprooting the winter cycle, appropriated the Roman idea, placing Christmas at the darkest point of the year. From the Germanic peoples came the evergreen tree, a symbol of life that does not perish even beneath snow and darkness; from the Scandinavians — Odin, flying through the Yule night sky with spirits. There’s no record of why those spirits became reindeer, but the transformation from a grim, bearded god into a kindly gift-bearer required many more centuries.

Until the nineteenth century, the New Year was either a religious or an administrative event. But as the influence of the state — and its accompanying bureaucracy — expanded into human life, it became a convenient synchronisation point for labour cycles, contracts, and tax reporting. The holiday turned into a tool for managing time and the economy. At the same time, a new urban bourgeois class emerged in Europe and the United States — one with money, leisure, and a need to confirm its status. New Year and Christmas became a season of consumption, and Haddon Sundblom’s illustrations for Coca-Cola elevated Santa to its central symbol.

The first country to officially enshrine the first of January as its principal state holiday was the Soviet Union. Religion and old rituals were to be eradicated, but depriving society of a transition point seemed dangerous. Christmas was therefore removed, and a secular, ideologically neutral New Year was retained. In the 1920s, even the Christmas tree was banned — but in 1935 it was restored, crowned not with the Star of Bethlehem but with a red star. Santa was replaced by Ded Moroz — not a god, but still a mediator — and Snegurochka appeared with gifts, not as miracles, but as rewards.

After the Second World War, the New Year became an ideal symbolic instrument beyond religions and blocs of influence. It served as a collective gesture for both victors and vanquished: we survived, we ended chaos, therefore we are worthy of creating a new world. This didn’t last long. In the early 1950s, television replaced the priest during the celebration, gathering millions of families and groups before its screens on New Year’s Eve. The turning of the year ceased to be the domain of temples; it became a media event. In 1962, the USSR aired its first Goluboy Ogonyok New Year show, and a decade later NBC launched Dick Clark’s New Year’s Rockin’ Eve — a show with live broadcasts from Times Square, hosts, music, the mandatory countdown, and highly marketable advertising slots.

The ritual of renewal shifted from the symbolic to the overtly consumerist. Its primary aim became the accumulation of pseudo-artefacts that one has taken along or given to others. The event lost faith but achieved maximum conversion in monetary terms. And yet the New Year still fulfils an important function: it allows us to discard the old without explanation, to fill ourselves with promises, and to ignite inside ourselves a small ray of hope that the next morning everything will be different.

This year, my ten-year-old daughter is not writing a letter to Santa asking for something material, she has just one wish for him to fulfil. What it will be, I do not know — and therefore cannot even attempt to fulfil it. But I sincerely wish that the fairy tale and faith in miracles such as the rising of Sirius over Egypt may live as long as possible in the heart of every person, regardless of age, nationality, or religion.

And finally… I don’t have half a million dollars to charter a business jet and circle the globe in twenty-four hours without missing a single time zone. But the task is entirely achievable: stretch the pleasure across the entire year and make it truly New. In February, visit the Spring Festival in China; in March, fly to Iran for Nowruz; in April, to Thailand for Songkran. In June, mark Hijra with Muslims; in July, Enkutatash with Ethiopians; and in autumn, Rosh Hashanah with Jews and Diwali with Hindus. To assemble the entire ritual heritage of humanity into a single route with one sole purpose: to defeat chaos, restore harmony to the world, and remind people of their true purpose — helping the gods maintain order.

Comments are closed.

1 Comment.

Wonderful