A Nightmarish Dream of Zweig: A young team has created a play based on the autobiographical novel of the writer.

The premiere of the play The World of Yesterday, based on the novel by Stefan Zweig and directed by Anna Ostrovskaya, was performed at the Camden Fringe Festival. The enormous, very complex novel by Zweig has been transformed by Anna Ostrovskaya into a play that combines fiction and reality, but the entire story feels more like a nightmare—or the delirium of the protagonist nearing death.

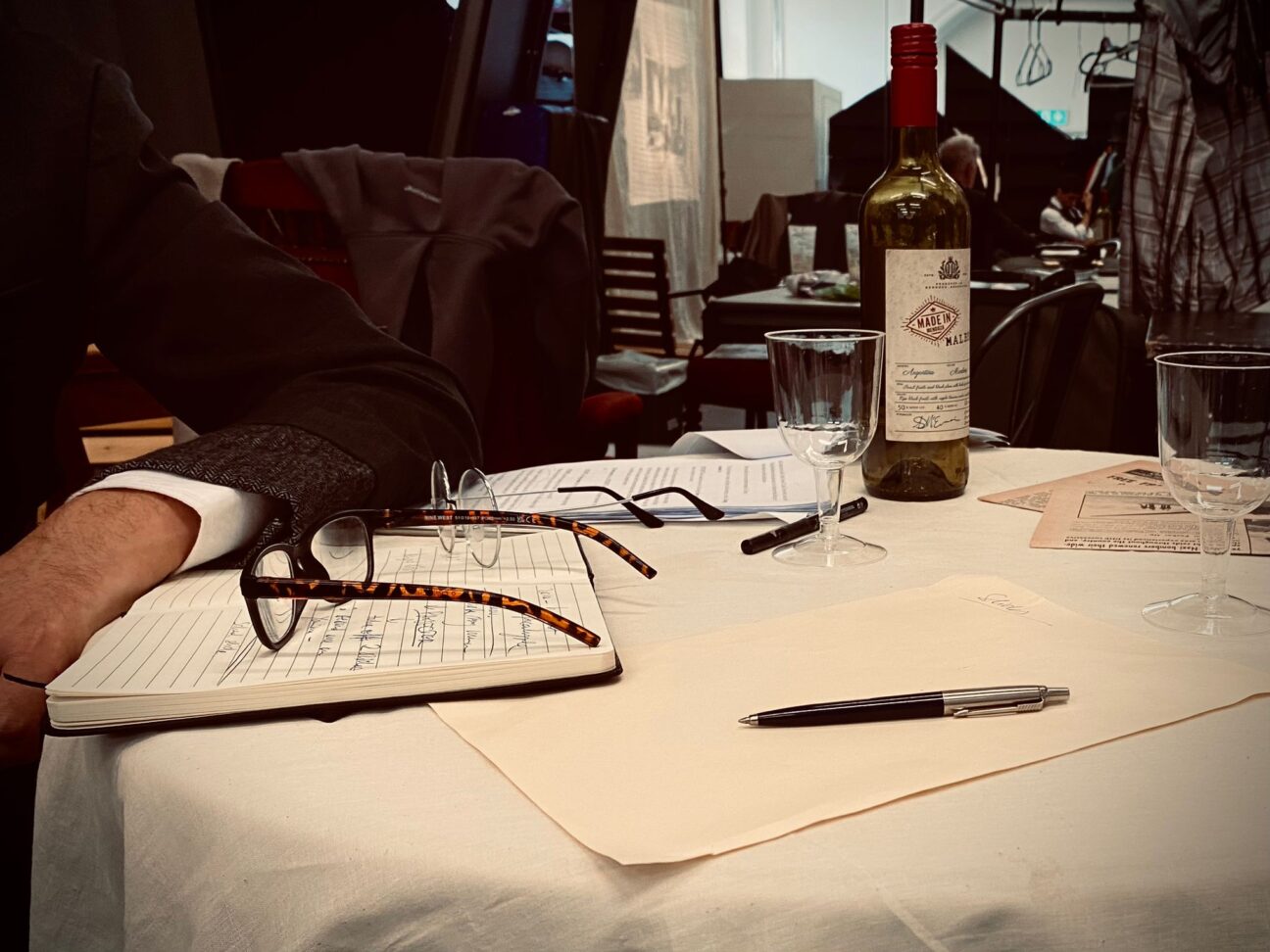

The setting includes a few tables with white tablecloths, wooden chairs, a sprawling projector, and a white sheet serving as the backdrop. In this minimalistic environment, the action unfolds over the course of an hour.

The genre of the play is cabaret, but there is no glitter, feathers, flashing lights, or triumphant music to entertain a champagne-filled audience. There are fishnet stockings, though—but more on that later.

It quickly becomes apparent that the society gathered in this cabaret is filled with hopelessness and a dull confusion—as if the main mirror has shattered into pieces, the orchestra has scattered, the flowers have withered, and only a few false notes linger in the air. Instead of a full orchestra, there’s just one guitarist (Pini Brown), and the champagne has dwindled to a half-empty bottle of wine.

Three versions of Zweig, representing different ages, sit at the tables, all connected by their childhood. The young Zweig is the most vivid and cohesive character, but his dream will ultimately destroy him many years later.

Here is young Stefan (Zora Owen): with delicate feminine features, a green velvet vest, and enormous glasses on his pink face, he is obsessed with a child’s heroism—a trait that Ostrovskaya’s Zweig could never rid himself of. He believes he can save the world, cradling it in his small hands like a butterfly, careful not to crush or ruin its wings.

The details of Zweig’s personal life are omitted; the intricacies of his romances and struggles between women are irrelevant here. The audience is invited into just one of the chambers of his mind, evidently the most important one, filled with his most painful and terrifying thoughts.

Horrifically grotesque events of world history seep into Zweig’s consciousness, destroying entire families, armies, and cities outside, while simultaneously shattering the writer’s inner world. Ostrovskaya meticulously constructs this suffocatingly terrifying process using minimal means, such as the actors’ physical movements (stage movement by Mari Camiloti) and props.

They dance between the tables, and a woman loses her partner but continues to move as if his hand is still on her waist. A soldier (Nadav Antman Ron)—not from any specific army but a collective image of a soldier, with a jacket and a beret over short curls—begins to undress, dancing to the music. Suddenly, the removal of his uniform turns into a striptease, and underneath his trousers, he reveals dainty fishnet stockings. The soldier is not a prostitute or a dancer, but he is being sold, his life a bargaining chip, soaked in blood that stains his shirt.

The terrifying dream, heavy and unbearably fast-moving towards a tragic finale, flows from one war to another—from the First World War to the Second. Different perspectives clash, and people turn into monstrous demons, their faces contorted, tongues sticking out of open mouths, eyes rolling in their sockets. Then, exhausted, they slump over the chairs like deflated balloons and gently roll onto the floor at the slightest touch.

The characters in Zweig’s consciousness—men and women, books and photographs, blood and songs—are intertwined. Songs like Bei Mir Bistu Shein and My Yiddishe Momme(sung by Pini Brown) are central, with themes of racism and antisemitism being particularly significant in the play. Theodore Herzl emerges from this nightmarish carousel, shouting and singing his ideas in a crystal-clear female voice—played by Zuza Tehanu. Her luxurious green dress and rain-like chestnut hair are not surprising: this is a dream, an illusion, a delusion. The beautiful woman represents beautiful ideas.

The other two Zweigs—Stefan in the middle of his life (Yanina Hope) and Stefan at the end (Adam Hypki)—are also present. The middle-aged Stefan, dressed in a military-style jacket and the same glasses, has not yet lost the intention to save the world, but there is more despair than desire in this desperate wish. As the role is passed from actor to actor, Ostrovskaya forces the image of Zweig to change both externally and internally, as each actor draws on their own nature. Throughout the play, the sense of some kind of oppressive weight on the Stefans never leaves, and the longer the character lives, the more apparent this burden becomes. At some point, the oppression turns into a jerky, broken malfunction.

But the most horrifying character in The World of Yesterday is the birthday gift that the elder Zweig receives on his anniversary. Wrapped in bright, multicolored paper, tied with ribbons, and with a red bag on its head, the Gift (Tanya Lyalina) marches across the stage like a wind-up plush bunny. Its beautiful face, whitened with makeup, turns into a monstrous grin of death. Especially with the drawn-on black mustache under its nose, and especially when it raises its hand in a Nazi salute (prompting several outraged audience members to leave the hall), only to reveal that the hand is stuck, and the Gift is simply leaning against the wall with it. The gesture, though made for utilitarian purposes, cannot hide the horror of the action.

Thus, a stifling horror is created on stage and spills into the audience, provoking disgust and revulsion. It makes you want to distance yourself, turn away, and switch it all off—but there is no “stop” button in the play.

It is the Gift that pours the poison for Zweig, and the allusion is clear: the writer is killed by the Hitler regime, by the Second World War, by the second wave of senseless brutality against which he is powerless.

There are no direct analogies to reality in the play; everything is focused on Zweig and his time, but the parallels are, of course, drawn.

Despite the tragic events on stage, The World of Yesterday is a very young, fierce, and bold production. Consider this: taking such a bone-crushingly complex novel, little-known to readers, writing a play based on it, staging it with minimal resources but immense energy, and with an international team—this is a theatrical feat, an hour-long triumph.

In the play, Zweig is defeated. But the performance itself and its creators are not.