One of the most exciting theatres outside the West End is staging Tom Stoppard. ‘The Invention of Love’, which premiered at the National Theatre in 1997, can be seen at Hampstead Theatre until 1 February. There are a couple of weeks left to catch it, while there are very few or no tickets left for most performances. Britain’s most famous modern playwright, Sir Tom Stoppard, who could probably target central London as well, has allowed Hampstead Theatre, that since its foundation in 1959 (as the Hampstead Theatre Club initially) is specialising in contemporary drama, one of his less well-known popular plays. Ten years or so earlier, the play had also been produced by students of Oxford University Drama Society – an exact hit, since Oxford is one the main settings in the play. Then Tom Stoppard came to see it in person and called it the best production of the play he had ever seen. But the playwright doesn’t have much choice – the play can’t boast a very long stage life, and the Hampstead production is only the second revival of the play in Britain, 27 years after its premiere. And one sees why.

Immersion in Stoppard at Hampstead

This is a play that requires deep immersion to appreciate Stoppard’s subtle intellectual humour (this time thinning to little-understood jokes about Latin poets and Latin quotations), as well as the ability to synthesise knowledge of philosophy, history of education, history of journalism, history of Latin editions, and the history of the late 19th and early 20th century England. To make the audience’s task a little easier, the programme prepared by Hampstead Theatre contains information about all the historical characters, a kind of ‘who’s who’ of the play, and without it we could be completely lost. The audience will also need theatre savviness and knowledge of the conventions of theatrical thought to understand the complex montage of memories of one man, created by one of the greatest and complex playwrights of the twenty-first century – Sir Tom Stoppard.

‘The Invention of Love’ is about a former Oxford student, the classical philologist and poet Alfred Edward Housman, who, despite failing to graduate from Oxford, later taught Latin at Cambridge, worked on a commentary on the collected works of the astronomer Marcus Manilius, and published two collections of poetry, ‘A Shropshire Lad’ (1896) and ‘Last Poems’ (1922), both of which are still famous. But Stoppard’s play approaches Housman’s biography in an inventive way – after all, its title requires it. Throughout the play we watch the deceased Housman in the company of Charon, who will soon help him across the River Styx, watching the scenes Housman’s memory brings him. Here different years, characters and epochs mix, as is common for Stoppard – for instance, or there is a conversation between the young and the already dead Housman – they are the two main protagonists of the play. The play has some very witty references to Jerome K. Jerome’s ‘Three Men in a Boat’, the characters of ‘The Invention of Love’ include Oscar Wilde (graduate of Magdalen College, Oxford), art critic John Ruskin (who taught at Oxford), Housman’s Oxford classmate, future British Museum employee and Shakespeare scholar Alfred Pollard, several journalists and real-life Oxford professors. The play is complex even for slow and thoughtful reading (there is much to google here), has Latin quotations and lengthy monologues.

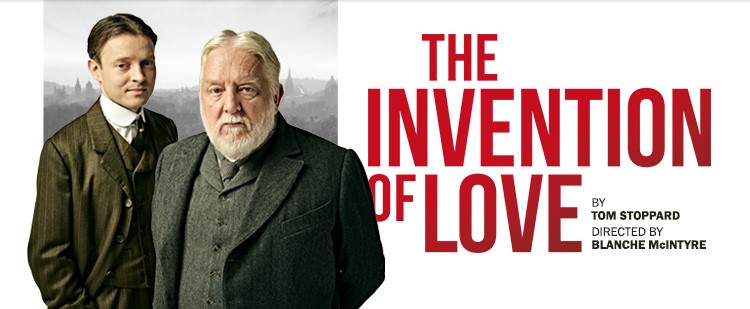

Director Blanche McIntyre has taken on a seemingly impossible task. The play is very difficult to visualise on stage as it is essentially a play to be read, a memory play, where all the scenes take place in the main character’s head in a kind of posthumous reverie. Scenographer Morgan Large and lighting designer Peter Mumford create an empty circle on stage in which the action takes place. What is it, an Oxford croquet lawn? The circle of knowledge once drawn by Socrates? The eternal circle of movement and return? All of these at the same time? Occasionally, in a separate cube above the stage, a running Moses Jackson (Ben Lloyd-Hughes) appears. He is a friend and a muse of our protagonist, Housman admires Jackson (he later realises he is in love with him, and invents and understands love experienced live), but whom he never gets one step closer to, as their worlds are too different. Jackson doesn’t have to learn to understand things that Houseman painfully discovers throughout the play. Only Housman reinvents love, as he is also a poet, as his Latin predecessors. In front of the black circle there sometimes appears a bench, and it is a place to watch what is happening below. Here, on some elevation, appears the actor Simon Russel Beale. In an act of actor’s virtuosity he manages to brilliantly convey the complex sparks of Stoppard’s intellectually complex humour. Here, in the same circle, we see the ‘moving’ boat with three young students, riding on the Thames to Iffley and back (as though they were the prototypes for the novel ‘Three Men in a Boat’). There is no water on stage, actors move, holding oars with upper parts of their bodies appearing on top of the ‘boat’, and legs moving the construction below.

Here, within this circle, the actors play imaginary cricket, have an imaginary picnic in Ealing (the action later moves to London), have conversations about raising the age of a woman’s consent to sex in an imaginary London newspaper editorial office, and meet for tutorials in imaginary Oxford classes. The problem with this play is that McIntyre leaves too much of the imaginary to the audience’s imagination, and here our imagination has no solid ground to work on successfully, as Stoppard’s play is made up of unknown facts and presents people not very familiar to the general public and not very well known facts of their biography on stage. We don’t have the facts to feed into the imaginary picture, and as a result we stumble.

The audience listens to long monologues, hears a lot of facts, mentions of Oxford, dissections of Latin poets, talks about different editions of Latin poets, but behind this – and this is the problem of both Stoppard and the director – some may not catch the essence of the play. And the essence is that once the reference to love and the feeling of love first appeared in Latin poetry, they later became an integral part of our lives, this feeling later became clear to modern people as well. Stoppard’s idea is that without the Latin poets we would never have understood what we are experiencing, we would never have learnt in the everydayness of life that love is fleeting, strong and eternal, as it is something appearing in the heart by chance – ‘it just happened’, but might stay forever. As it happened to Catullus, as it happened to Horace.

Blanche McIntyre demands that we immerse ourselves in the play’s complex philosophical matters without making it easy for us either with sets for understanding the shifting locations of the action, or by clearly working with Stoppard’s world of memories and collages of time. As a result, the complex play has become even more confusing on stage, with the actors playing several characters without really changing their black suits and bowler hats, not helping us to work out who is who. So, having tried to immerse ourselves in it, despite excellent work from Matthew Tennyson (the young Houseman) and Simon Russell Beale (Alfred Edward Housman), we may not come to the surface of these deep waters in the end. To drown in a Tom Stoppard play is undoubtedly an honour one might look forward to, but to direct Stoppard’s play without attempting to visually simplify it and expose its structural underpinnings is undoubtedly a disservice done to the maitre of modern theatre and drama. It could have been easier presented and explained, and we could have fallen in love with it. Now this love needs inventing through reading the play after the show.