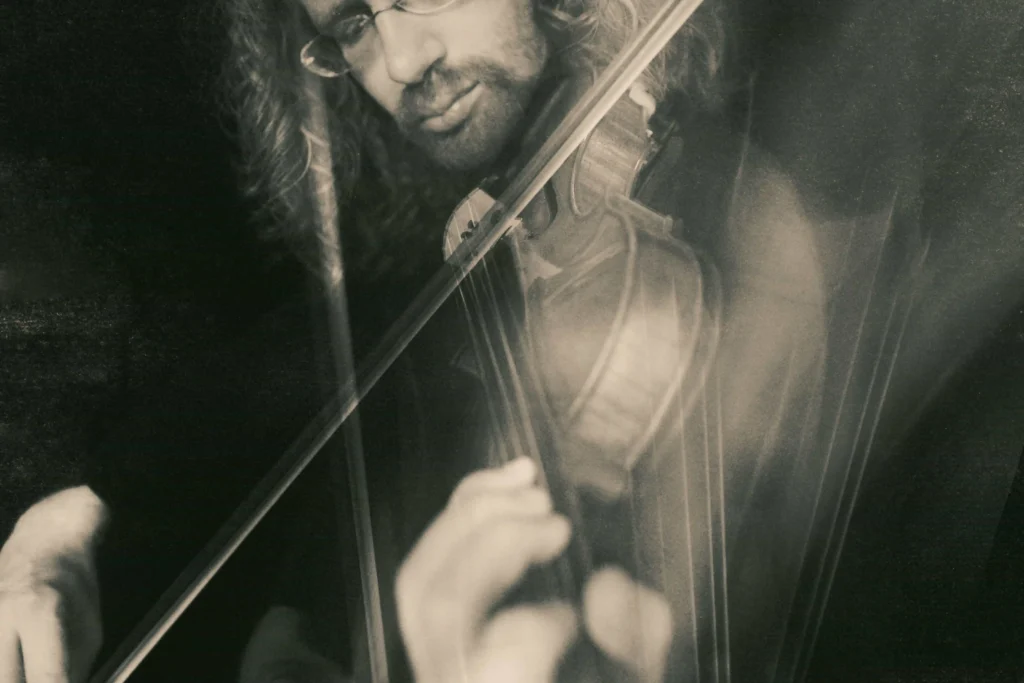

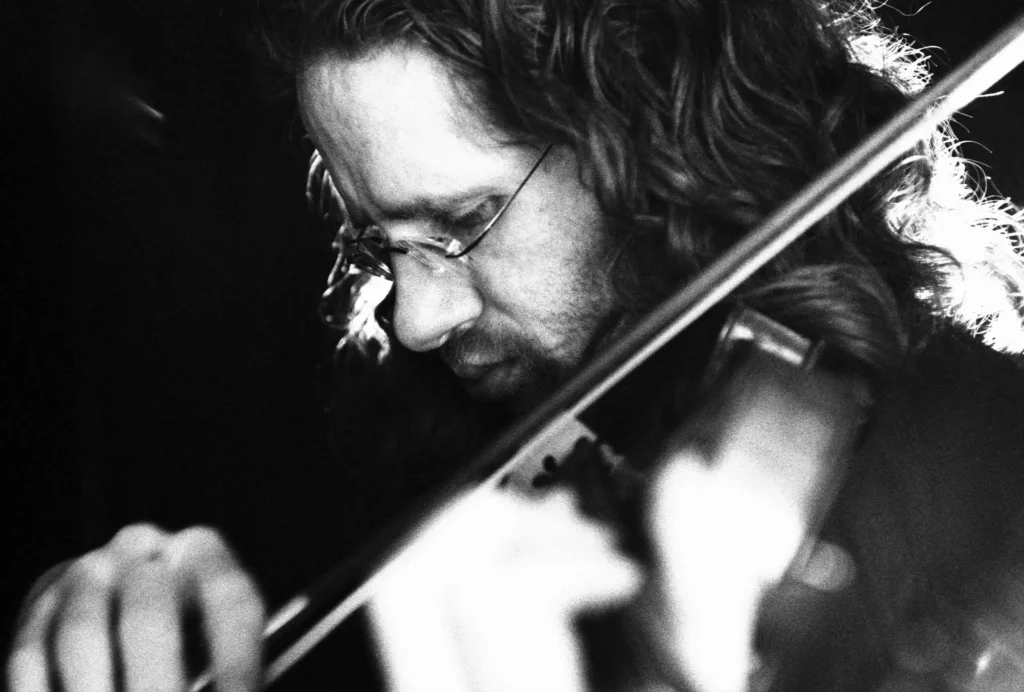

Roman Mints: “Restoring justice has special meaning for me”

One of the brightest and most original musicians of his generation, violinist Roman Mints has performed with dozens of renowned musicians and conductors, and his recordings have been released on leading labels. After the war began, Mints left Russia and returned to the United Kingdom, where he now teaches extensively and develops new projects.

Today, Mints is at the center of musical life: his new album Kol Nidre is being released, and in January he will present the Another Music Festival in London.

We spoke with him about these and other events, in which — as in his entire life — freedom, responsibility, and an endless faith in the power of music intertwine.

What does teaching mean to you?

I often meet people who say, “Teaching is terribly hard and exhausting.”

For me, teaching turned out to be a natural part of who I am — though I never originally planned to do it.

So it was a forced step?

When I was young, I was an assistant to my professor, Felix Andrievsky, so I spent a lot of time in his lessons. I had lived here [in the UK] since 1994, but later I ended up in Moscow, where I never really saw myself within the teaching system. I just couldn’t stand the atmosphere.

The only thing I did there was teach chamber ensemble — a subject much freer than violin. And I did it mainly so that I could offer children an alternative to the reality I saw around me. But that didn’t last long; the environment simply rejected me. The years I spent in Britain made me a different person.

Is there a big difference between that environment and this one?

The mentality is completely different. Musical education reflects the general mentality of a society! Here, coercion has long been discouraged.

Yes, it’s a double-edged sword — the overall level may not be as high, but people’s internal sense of freedom is different.

When I hear my students answer me with, “I think this should be done differently,” I realize I didn’t have that inner freedom before I first left Russia.

And that’s good! You shouldn’t have a sixteen-ton weight pressing down on you all the time.

Many of my students came from what you might call post-Soviet schools. I keep telling them: I don’t need you to play “correctly.” You’re not playing to fulfill the markings on the page. You can’t be a slave to those little symbols. And most importantly — once you start thinking musically, truly playing music, everything becomes easier.

The Soviet and post-Soviet system of music education is built like this: countless people struggle to reach the top, and whoever survives deserves praise. But many don’t survive, and no one cares about their fate. The stronger ones make it and become somebody. The system works — it produces great musicians. But to grow out of it, you need tremendous strength.

In Britain, about 80% of children play musical instruments at an amateur level — that kind of fertile environment simply doesn’t exist in Russia. There, it’s a narrow circle where parents force their children to study music — a sort of intellectual family pastime. But here you meet truly talented people who, thanks to their ability and a good teacher at the right moment, grow into major musicians.

Of course, there’s no longer a conveyor belt like in the Soviet Union. There have been attempts to borrow from that experience: for instance, the Menuhin School is modeled directly on the Moscow Central Music School — no one even hid that fact. Yehudi Menuhin himself visited Moscow, saw the CMS, and happened to attend a lesson with my professor.

Your new album Kol Nidre is coming out soon. That’s the name of the text recited on Yom Kippur, right?

Before releasing the album, I really dug deep into the subject to understand it. Kol Nidre is a strange text — if you’re outside the tradition, it’s hard to grasp, and even within Judaism, it’s interpreted differently.

It’s often been used to attack Jews, because the text essentially says, “The vows I make shall be null and void.” It’s not even a prayer in essence. I read that it’s more like a legal formula, a declaration in Aramaic — the spoken language of the time.

From what I understand, in Judaism making vows is considered a bad idea, because failing to keep a vow is a grave sin.

So you’re not supposed to make them — and when a person acknowledges their own weakness at the start of the year and says, “If I stumble, it’s not intentional,” that’s the point.

But that’s not what mattered most to me. What mattered were the threads that tie me to who I am. I didn’t grow up in a religious environment — we didn’t speak Yiddish at home — but certain things were still preserved.

For example, I had a record where Hungarian Jews sang Kol Nidre, or I’d go to a concert and hear that music performed. My parents would set the table for Passover and say a few words, because it mattered to them. There were pastries for Purim.

These fragments of a culture that had died within a single family — that’s what shapes you. I now realize that these little things define that part of me called identity.

The Kol Nidre melody has long entered European music — it somehow stuck. On my record, there’s a Kol Nidre by Mikhail Erdenko, from the famous Gypsy musical dynasty. He dedicated the piece to Leo Tolstoy — when Erdenko visited him, Tolstoy said, “Let the old man weep — play Kol Nidre.”

And that image — a Romani-born classical violinist playing a Jewish prayer for the great Russian writer in Yasnaya Polyana, and Tolstoy weeping — that, to me, sums up who I am.

Would you call this album contemporary classical music?

I wouldn’t. It sits at the intersection of genres. The title piece is by John Zorn, a legend of the avant-garde jazz scene. He sometimes writes music in notation, but he comes from a completely different world.

As for other pieces, there’s a bit of this, a bit of that — all of them have personal meaning to me. But I try not to play them too “academically.”

Which brings us back to the question of notation…

Yes — these are things you can’t write down.

The deification of the composer — putting him on a pedestal as an untouchable figure — really only appeared in the 19th century. Before that, such idolization didn’t exist at all. So there wasn’t this trembling reverence toward written notes.

Notation only captured part of the music. If you listen to recordings of Clara Schumann’s students — who actually heard Brahms play — you’ll hear that their performance has nothing to do with simply “playing what’s written.”

Composers wrote knowing that no one would play it the way we do today…

…meaning strictly by the book and the metronome?

Exactly. Because when a composer indicated a metronome mark, it was just an approximate guide to the movement he had in mind.

But within that movement, there can’t be two identical phrases — and there can be no blind obedience to the metronome.

Another Music Festival in London isn’t the first festival you’ve organized.

No — the first was back in the 1990s in Moscow with my friend Dmitry Bulgakov. He was 18, I was 20 — we were just kids.

The festival was called Return (Vozvrashchenie). It lasted 25 years and became a real institution, loved by many. But at first, it was just this chaotic idea:

“Let’s do a festival?”

“Sure!”

“Hey, Vasya, will you play?”

“Yeah, I’ll play!”

No one told us about the difficulties — so there weren’t any.

In later years we even did crowdfunding — people not only bought tickets, they supported the festival financially. That was important not just for the money, but because it showed that people cared. Their 500 rubles said: “This matters to me.”

But everything in life has its time, and the time of Return ended — right as the war began. The reality I had tried to ignore caught up with me.

I left Russia, and while I was hanging in that emotional limbo, I thought maybe I should just focus on teaching. But it’s hard to run away from yourself — and I’m someone who needs to create things, to make events happen, for myself and for others.

I’ve always been amazed that people see someone incredibly talented and, even if they have the means, don’t help them — not because they don’t want to, but because it just doesn’t occur to them.

But that’s not how I’m wired. I’ve stopped being ashamed of it. If I can make something happen — I do it, even if it hurts my “image” as a musician.

Seriously? It hurts your image?

Of course! If you organize things, people think of you as an organizer, not a musician.

But my life has taught me: when you have an idea, make it happen — whether it’s a performance, a commission, or any other project.

One of the impulses behind Another Music Festival actually came during the pandemic.

I’ve got a long-running chat group with a few close friends. One day, during lockdown, composer Alexey Kurbatovcomplained to violist Mikhail Rudoy: “I have no inspiration, no work, no money.”

Misha said, “Then I’ll commission a piece from you. Write a piano quartet.”

So Alexey wrote it. Then the war started… and five years later, the piece still hadn’t been performed.

When I learned about it, I decided it must be premiered — with Misha performing, since it’s dedicated to him. I built the festival program around that premiere.

It turned out that pianist Vadym Kholodenko, another member of the chat and a great artist, happened to be performing in the UK and could arrive two days early to play the quartet.

Misha agreed to come too. The only person refusing to come was the composer — he didn’t want to apply for a visa!

Is there a difference between organizing a festival in the UK and in Russia?

Probably, yes.

In the last years of Return, the festival had such a reputation that some things were easy — but in Russia, you always run into absurd obstacles. Always. You’re constantly fighting something.

For example, for years we sold booklets before concerts, and then suddenly, without warning, we were told that by order of the rector, we couldn’t sell them anymore — nor could we put out a donation box. So at the final festival, we just handed them out for free.

In Britain, the main issue is practical: in Moscow, I could find rehearsal space through connections; here, you just have to raise money to rent it.

The Moscow festival was also famous for having no artist fees — everyone played out of pure enthusiasm. Many performers came because, although they had successful careers, the chance to perform at the legendary Moscow Conservatory was tempting, and we gave them that.

Here, it’s similar — you have to build relationships, make people want to work with you. If you’ve got lots of money, you can just buy everything, sure — but if you don’t, you have to build trust.

I managed to connect with St John’s Waterloo, where the festival will take place. I showed them what I can do by organizing a charity concert last year — they saw how it went and what kind of impact it had. So now they see value in having me there — it’s a mutually beneficial partnership.

Why is it called Another Music Festival?

Because in London there’s so much happening every day with big stars. If you say you’re organizing a festival, the first reaction is always: “What, another one?”

So I answer: “Yes — another one.”

But also, for many of us who were broken by the events of 2022, the search for self-definition is deeply relevant. Something that was yours has been taken away. Someone will say, “No one took it — you did it yourself,” but that’s not true.

I often meet people who’ve lost everything — for Russians, yes, it’s partly a choice. But most of my Ukrainian students lost what they had by force — because they were attacked, had to flee, and so on. Many have PTSD in varying degrees; some just break down in tears during a lesson.

That’s why I decided the first Another Music Festival would focus on the theme of immigrants. It’s such a rich topic. The program includes, for example, a 16th-century English composer who fled England for being Catholic and persecuted. Or Rachmaninoff, or Stravinsky.

Or Stefania Turkewich, the first Ukrainian female composer — an extraordinary figure. After World War II, she lived here in Britain, constantly sending her works to competitions, but no one ever accepted them. This country never really embraced her.

When you try to find her violin sonata — which one of my Ukrainian students will play — you’ll find only a single performance on YouTube, even in Ukraine. People give lectures about her, but most of her music remains unperformed.

Among the festival performers are many top-level musicians: Kristina Blaumane, principal cellist of the London Philharmonic Orchestra; Katya Apekisheva, professor at Guildhall; Natalia Lomeiko and Yuri Zhislin, professors at the Royal College; Vadym Kholodenko, as I mentioned; and many wonderful new colleagues like Hilary Cronin, Francis Gash, and Milena Simović.

And one more thing matters to me: recently, the small circle of Russian émigré intellectuals celebrated the anniversary of composer Leonid Desyatnikov, with whom I’ve long collaborated.

I find it strange that one of his finest works, The Leaden Echo, written on a text by Gerard Manley Hopkins, has never been performed here — even though that canonical text has been set to music many times.

I’ve heard several versions, and I’m convinced no one has captured it as perfectly as Desyatnikov did. It’s just wrong that such a work hasn’t been heard in the land of Hopkins himself.

So presenting it will be, for me, an act of restoring justice — which, come to think of it, is a recurring theme of this entire festival.

Comments are closed.

1 Comment.

Stella Yurovsky from Philadelphia