Signe, a 30-year-old barista from Oslo, is trapped in a dead-end job and zero popularity. She is in a toxic relationship with Thomas, an artist who makes sculptures from furniture he personally steals. Devoid of any discernibletalent yet brimming with envy, Signe craves attention and will seize any opportunity for a taste of fame, even at the cost of her own well-being—quite a fitting combination for theculture of distorted values.

“Sick of Myself”: A Cocktail of Vanity and Desperation

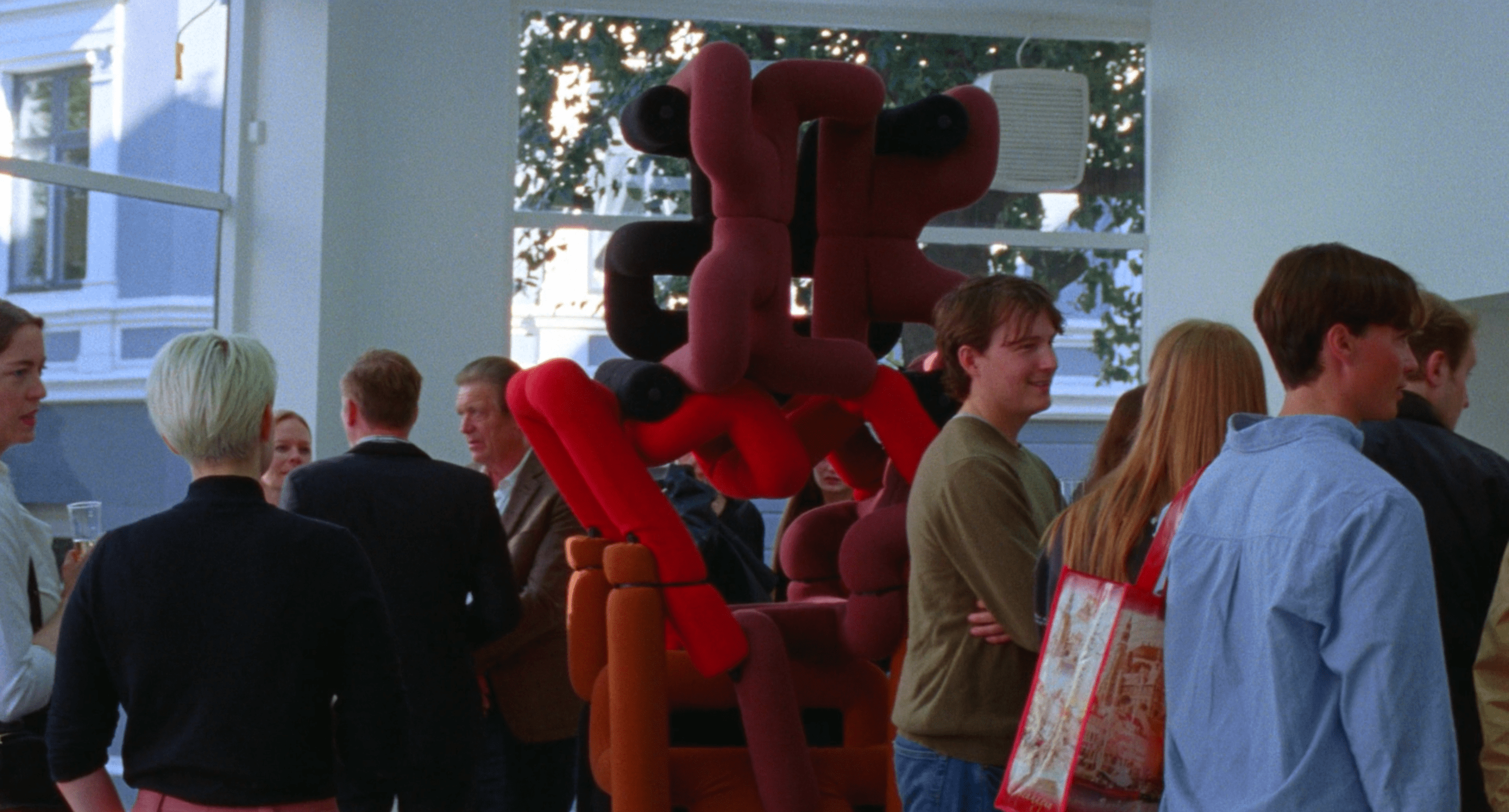

Signe’s proverbial 15 minutes of fame arrives not through her compulsive lie—faking an allergic reaction during Thomas’s speech at the dinner following the opening of his solo exhibition “Damages”—but through an unexpected act of heroism. When a bleeding stranger stumbles into the coffee shop during her shift,Signe, in a desperate bid to help, nearly employs her own body to close the wound. Shocked onlookers document the scene with their smartphones, and the police commend the brave employee for her civic-mindedness. “Anyone in my place would have done exactly the same,” Signe declares. Or does she say: “It happened completely instinctively”? Either way, emboldened by this taste of recognition, she now has an audacious scheme to attain greater notoriety.

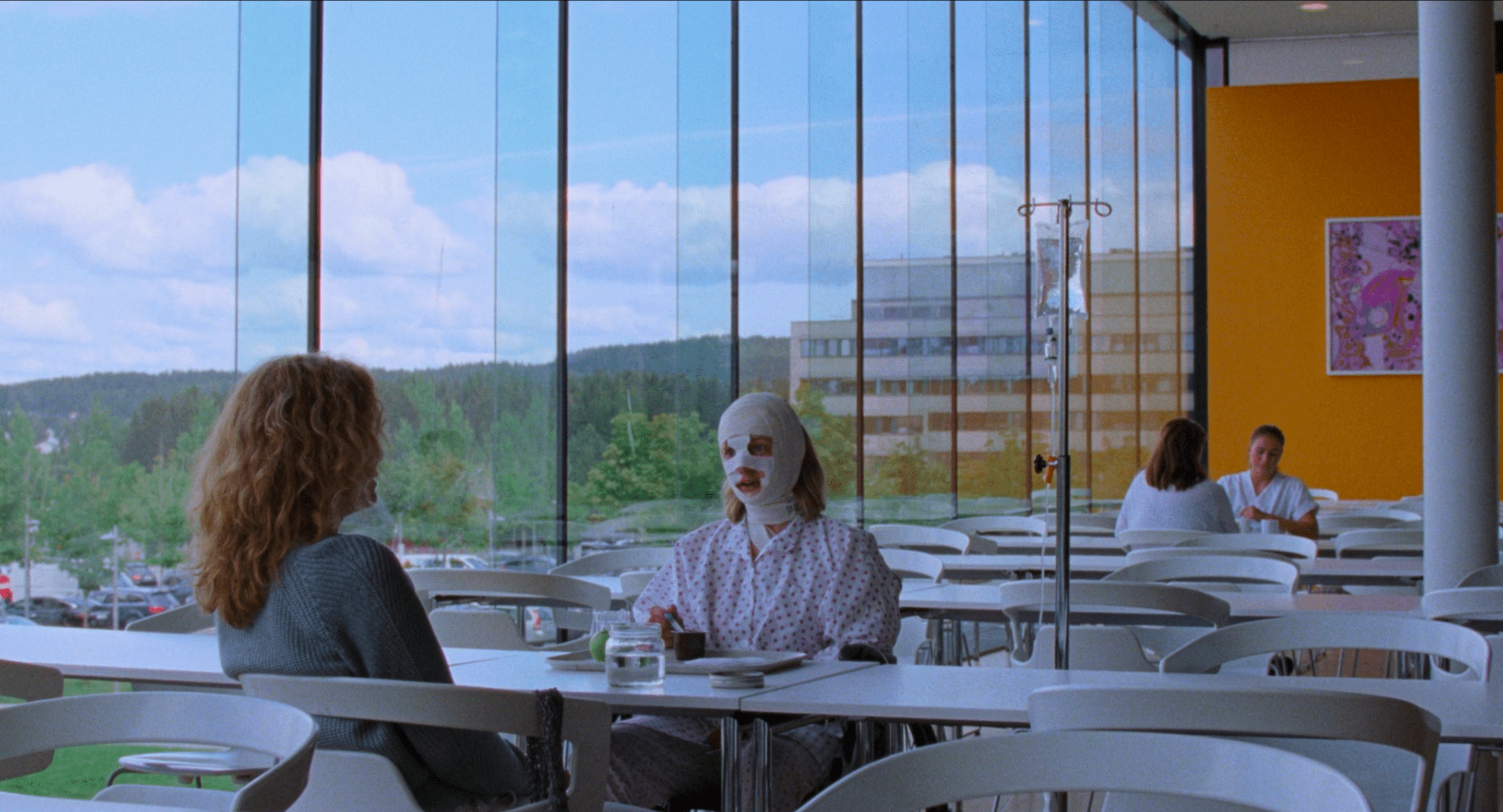

Becoming a martyr doesn’t work on the first try: a fierce-looking but ultimately decorous Scandinavian dog refuses to maul Signe’s offered throat. However, the internet easily yields a Russian pharmaceutical drug, Lidexol, which a familiar dealer agrees to procure. Lidexol has horrific side effects, but aren’t blood vomiting and skin problems a trivial price to pay for a potential outpouring of sympathy and attention? Signe’s absurd self-destructive path leads to some initial achievements: Thomas develops a warm feeling of care, a tabloid features a big interview with the victim of Russian pharmacology, and the inclusive casual wear brand “Regardless” invites Signe to be the face of their new advertising campaign. It appears to be the a trajectory towards success: Signe becomes an icon, a legend—if only for a fleeting moment.

“Sick of Myself” stands as an ideological predecessor to Kristoffer Borgli’s more resonant and mainstream “Dream Scenario” (2023), featuring Nicolas Cage. Both films dissect the intricacies of a competitive society, the nature of public judgment, and the rapid shift from acclaim to disdain and collective hate. Borgli portrays the futility of communication, the world’s inherent madness, and the randomness of events, effectively pioneering an “existentialism for the social media age.” In the vein of Ruben Östlund and Joachim Trier, Borgli shows what it means to be a Scandinavian narcissist in its most unflattering form. The result, however, is more relevant and authenticthan that of Östlund, who has twice captivated Cannes with his scathing critique of a society mired in hypocrisy and sanctimonious moralism.

As the plot of “Sick of Myself” develops, it plumbs the depths of Signe’s physiological and psychological landscape. Despite the tribulations, her thirst for recognition remains unquenched. “Narcissists are the ones who win,” she resolutely believes. Dramaturgically, this cinematic provocation maintains its allure until one realizes that the depicted crisis of social reality is doomed to remain mired in its inherent futility, never achieving catharsis. Instead, it traverses a predetermined circle, alighting upon nodes of self-destruction, apathy, stress, and other waypoints of the human condition. Within this cycle yawns an abyss so profound that neither humor, black humor, remorse, nor even the faint glimmer of universal enlightenment can bridge it. Achieving even a semblance of success proves no more fulfilling than wallowing in idleness or existing in the shadow of another’s fame. When approaching the first and likely sole viewing, it behooves the viewer to bear this in mind.