As the saying goes, if you want to offend no one, you’d better offend everyone at once.

The Art Market Through the Eyes of a Professional and an Observer

So I’ll take the risk and share some observations — not claiming absolute truth — about the art market, art education, and all things art-related in Britain over the past 15 years, from the perspective of an artist and a viewer.

Everything flows, everything changes. Sometimes it’s hard to believe just how radically and abruptly trends flip. One minute, a crowd confidently charges from point A to point B — and the next, it turns around at full speed and rushes back the other way. But one thing remains constant: some people make art, others teach it, some display or buy it. And this — at times exuberant, at times toxic — little ecosystem keeps growing, undeterred by the schemes of evil or yet another economic recession.

It’s astonishing! Neither pandemics, nor wars, nor crises have managed to crush the artist’s drive to create or the art lover’s passion to adore. Within this remarkable constancy, three periods can be traced — flowing into one another here and there like pigments on a wet canvas.

Period 1: Conceptual Obscurity

(roughly from the late 1960s to 2014, with interruptions)

Many artists still remember what it was like to do, say, painting 10 or 15 years ago.

You’d constantly be asked: “Why, when everything’s on fire (did we even know back then what ‘everything’s on fire’ really meant?), are you sitting here painting pretty pictures, selling an outdated medium, and endlessly repeating yourself? Have you even tried turning your brain on, comrade? The real brave artists are out there building complex trash installations in the name of progress, while you’re just selling your soul to capitalism and clinging to the past.”

In 2012, I was doing a master’s degree in art at Kingston University. I painted, more or less in secret — afraid to show anyone. Because anytime someone brought in a painting for critique, the tutors would suggest turning it to face the wall. Or burning it, turning the ashes into jelly, and eating it. (And no, that’s not my fevered imagination.)

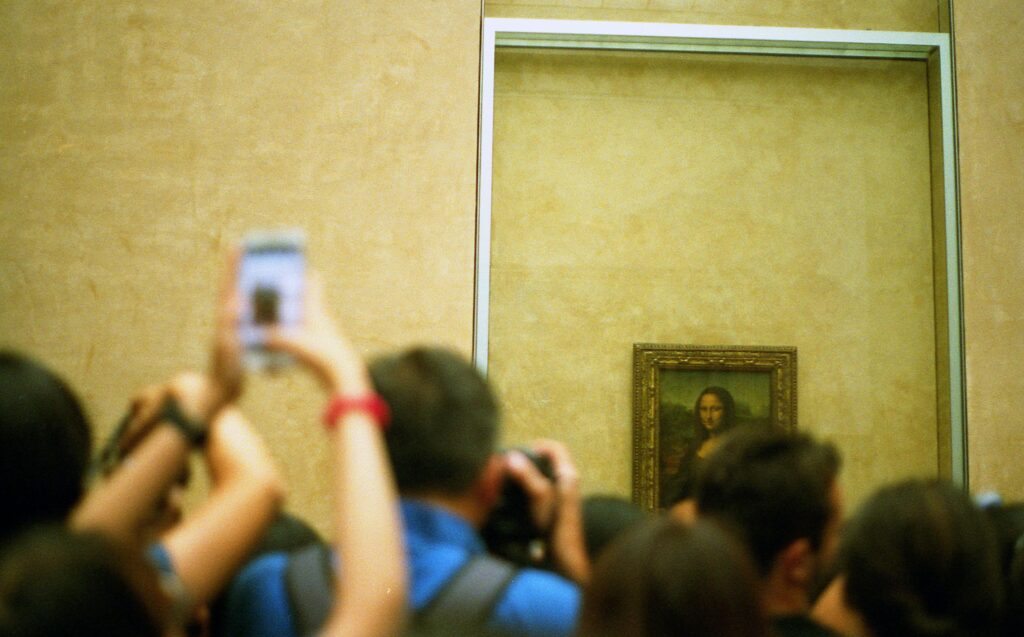

I also recall a very commercial gallery, Hauser & Wirth, exhibiting a giant ark overflowing with sacks. Any work — no matter how obscure — was accompanied by a dense wall of text proving the artist definitely knew who Deleuze was, and what an oneirosignum might be. Viewers wandered through exhibitions wearing wise expressions, murmuring things like, “Elegant. Very elegant.” The ability to appreciate visual poverty and dense theory was the mark of refined taste.

And yet, wealthy collectors in sleek glasses happily bought installations made of cardboard scraps and beer cans — as long as they were doused in Deleuzian dressing. The market was lively enough to sell almost anything. People assumed such art would climb in value, just like boring but reliable investments like Picasso or Gauguin.

Whatever didn’t sell was usually dumped in the nearest bin — a not insignificant amount of “important” contemporary art now floats around on garbage islands in the Indian Ocean.

The fact that these “elegant” artists rarely earned a penny from their art and mostly worked as graphic designers was not only accepted — it was seen as honourable.

It elevated them above the lowliness of bedroom paintings and gallery sales. Painting still existed — it even sold now and then — but only if served with a complex theoretical post-post-meta-meta garnish, with a faint aftertaste of capitalism critique.

The audience, sipping Cristal, did not object.

Meanwhile, the British art world was almost entirely white and British. Artists and collectors were submerged up to their Carrara-marble bald spots in a very specific European and North American context. Despite the fashionable anti-colonial wailing, there was little real interest in anything outside it.

Period 2: Identities, Textiles, and the Naïve

(the peak period: 2014–2020)

But the seeds of change were already sprouting from the very discourse that had dominated for decades. If you spend long enough critiquing European logocentrism, post-colonialism, and the like, eventually you have to start including people in art who aren’t white male grads of elite art schools. Migrants, people of other races, cultures, orientations, genders — and, as it turned out, not all of them wanted to read Deleuze and Bataille.

This shift might have remained theoretical if not for the arrival of international collectors and the sting of domestic recession. That combination started to whisper, not so subtly: if you keep letting only those in who know Benjamin Buchloh isn’t a brand of booze, the whole thing might just collapse. And so the art world was forced to admit: not all artists and collectors wear delicate glasses, sport pale noses, or hold degrees in philosophy.

Soon, long-winded explanations of “phenomenological regressions in media transformation” began to wither. In their place bloomed identity politics.

Artworks came with the justification that someone with this identity would naturally produce this kind of work. If you came from a local cult, it made perfect sense to weave or sculpt tributes to that background. But for those without such identities, it suddenly wasn’t clear what they should be doing. Everyone began digging for a rare, precious, minoritised trait in themselves.

Those who couldn’t find one no matter how hard they tried began expressing shame — about everything. That at least helped preserve the status quo. And so, despite the “textile biennale” of 2017 in Venice — filled with traditional weaving, female practices, and plenty of naïve ceramics — most successful artists remained white, cisgender, British or European men of a certain age.

What was most striking was how people who, just yesterday, couldn’t discuss the weather without citing “disjunctive synthesis” or “the empty signifier,” suddenly rediscovered tarot and horoscopes, occultism and shamanism. It was like watching former Soviet Young Communist Leaguers suddenly starting to cross themselves in the ’90s.

Painting began returning to the biennale and museum scene, but no longer accompanied by critical theory. After all, a canvas is a commodity and a relic of the European colonial tradition. Instead, works were now served with a unique identity sauce — suggesting that the painting organically sprouted from the artist’s origin, gender, or oppression. Suddenly, everyone remembered female spiritualist painters like Hilma af Klint and began making what was now called “spiritual abstraction”: smears and gestures on canvas born not of form or composition, but of trance, ancestral voices, and so on.

Period 3: Yet Another Return of Painting and Selling Your Soul to Satan (as Strategy)

It’s now hard to believe that Mayfair galleries once exhibited candy installations and life-sized bag-stuffed arks. These days, it’s tough to find a major gallery that doesn’t focus on painting. Most abstract painting shows still come with texts about how the artist “breaks boundaries” and “challenges everything” — because mass-market still loves a good rebel, why wouldn’t art? But usually, there’s no real political or conceptual backbone.

Why? Probably because no one wants to scare off the collector who wandered in by accident. No one expects them to know Foucault or care about obscure rituals. They just need to buy something — or the gallery shuts tomorrow. Be a slave trader, a serial killer — no problem. Just buy an abstract piece for your living room. The gallery will ensure the artist continues to “quietly deconstruct” the conventions of painting and sculpture, of femininity and masculinity, of human and too-human — but keeps silent on any real political issues with actual disagreement. It seems the capitalists have finally stopped funding critiques of themselves, and while minoritised identity is still “important,” it now feels more like inertia than a real trend. As for Deleuze — forget it. Irrelevant.

If you look, for instance, at the artists represented by one of London’s leading galleries, Hauser & Wirth, you could loosely divide them into three groups: esoterica and Deleuze; identity and the local; and painting with a dash of minoritarianism. The first group last exhibited sometime around 2012, the second in 2017, but those working with abstraction, scale, and painterliness — they were on yesterday.

In the biennale and museum context, things play out a little differently than in commercial galleries. There you’ll still find rugs, Deleuze, and a range of oppressed identities with declared political positions — though increasingly toothless ones. Still, painting is starting to creep in even there. Museums are often state-funded, which means they serve the interests and uphold the values a state wants to see reflected. In the European and American lens, the main institutional line remains tolerance — a leftist discourse in art that effectively acts as a mandatory uniform for any kind of public expression. As a result, any artist applying for a grant will try to wrap themselves in whatever identity and values the museum in question is looking to promote.

But state funding seems to be drying up. Projects feel increasingly commercial, saleable. It looks like the era of identity-leveraging may not last much longer. Which makes sense — you can’t run an election campaign on tolerance alone, and the broader ideological support for “everything good against everything bad” is fading fast. So now artists are left to sell their work more or less independently… And who shows up at that moment? That’s right — painting. After all, even if an artist comes from the most oppressed and marginalised background imaginable, you usually can’t tell from the painting. And if you discreetly omit a few personal details, you can even sell that same painting to the alt-right.

Sounds like good news, right? But some of these trends are worrying. First, it feels like support for the arts is shrinking from all sides — both public and private investment is dwindling. Second, the fact that the most popular medium is also the easiest to store and resell… doesn’t that suggest that more and more people are anticipating forced migration, a quick liquidation of collections, and a mad dash toward the Canadian border?

An Art Degree ≠ An Education

Another ever-shifting aspect of the art world is art education — the great machine that has churned out pale Deleuzians, vibrant rug-weavers, and abstract painters tearing down every boundary imaginable while muttering quietly into their sleeves. In the past 15 years, tuition fees at top British art schools have doubled, tripled, or even quadrupled. Meanwhile, student intake is growing across the board.

When I started the Painting course at the Royal College of Art in 2017, there were 45 of us in the cohort. Now, it’s about 150. In 2010, one student would occupy a studio space; by 2017, it was two per room; by 2025, it’ll be four. The number of one-to-one tutorials with tutors has dropped by almost a third since 2017, and with so many students, the quality of feedback has declined — it’s simply harder to remember each person. Queues for technical workshops and libraries grow in step with rising tuition fees. Universities are gradually turning into diploma vendors, and students into either cash cows or just plain customers.

Still, while diplomas from the RCA, Goldsmiths, or UAL are seen as valuable and offer career prospects (especially in China), people will continue to pay for prestigious degrees — even if the education part quietly disappears. This bubble will likely burst sooner or later, but when that happens is anyone’s guess. For now, everyone seems relatively content — except the rare student who wasn’t born into an oligarch’s family and can’t produce £50,000 a year for tuition (scholarships and student loans aren’t doing great either). But every year brings a fresh crop of students, and they don’t know how things were five years ago — they’ve got nothing to compare it to. So they manage to teach themselves on their one square metre of studio space.

Among the many dissatisfied are a few brave souls still determined to spread knowledge for something less than fifty grand. That’s how independent art schools are born. Trouble is, their independence often means they can’t sponsor student visas, and therefore can’t admit international students — who, by the way, pay three times as much as domestic ones. That makes it very tempting for mainstream institutions to accept only foreign applicants. You end up with courses where 90% of students speak to each other in Mandarin. And independent schools also struggle to compete with the juggernaut marketing machines of the RCA, UAL, and others.

The Artist as Investment

So what does this all mean for the market? Each year, more and more artists graduate, competition skyrockets (for example, this year the Jackson’s Art Prize had around 15,000 applicants), and it becomes easier and easier to find artists who fit a particular goal or niche perfectly. The days when an artist could afford to be erratic, unpredictable — unless you were Maurizio Cattelan-level — are gone. Artists are, first and foremost, an investment. That’s always been the case, but rarely has it been taken quite so literally.

With a massive oversupply of graduates, art programmes, and lagging demand, no one wants to invest in someone seen as “risky.” Maybe their work is too varied to be easily recognisable, or they’re the “wrong” nationality, or they speak too freely and might say something controversial tomorrow, leading collectors to panic. What the market wants are convenient, likeable artists — whose canvases can hang in a bedroom and show off the collector’s refined taste. And there’s no shortage of those. With such an abundant pool, you can select for maximum convenience and likability. Nothing personal — just business.

Another curious trend is the rise of very young artists getting picked up by top galleries straight out of their graduate shows. Who are they? More often than not, they’re producing abstract or semi-abstract painting, working diligently, carrying at least a faint whiff of minoritarian identity, and keeping a low profile. The formula goes like this: someone invests, someone promotes, deals are made with galleries and critics, the price goes up — profits are split.

Often, it’s a one-season wonder. Before they’ve had time to develop a real position in the art world, these artists get caught up in the whirlwind of hype, start to believe their every fart is art — which can work for a while, but rarely for long. After all, each year brings another batch of graduates whose work can be bought for £5,000 and maybe flipped for £200,000. But the work bought for £200,000 and resold for a million? That happens far less often. Former art stars are left reminiscing over their fifteen minutes of fame with a cup of tea and a splash of rum — just like those early 2010s Deleuze fans in quirky glasses who never quite managed to pivot in time.

***

These are just a few modest observations from inside the weird world of art. They may be a little disillusioning, but I’d like to return to the opening thought: art contains multitudes — it can be funny, tragic, cynical, touching, sublime, or gross. But one thing remains unchanged — art doesn’t disappear. There will always be something for artists and art lovers to do, something to enjoy. And it’s incredible, really: no matter what happens to the market, the museums, the galleries, or the world at large, people’s drive to create and experience art is impossible to kill.