The feverish pulse of the early 20th century demanded a new visual lexicon to capture the zeitgeist. Within artistic circles, an awareness of the “other self” intensified, leading to the realization that art’s essence lay not in directives (what should or must be done) or meticulous simulation of reality, but in the creator’s unique essence. This paradigm shift from old to new thinking was manifested in modernism: a movement that, while gaining rapid popularity, remained deeply rooted in personal expression, shaped by individual artistic genius. Though at times as unwieldy as the industrial mechanisms of the era, modernism proved remarkably adaptable, becoming a defining aesthetic phenomenon.

In the Eye of the Storm: The Content of the Paintings is Unknown to the Author

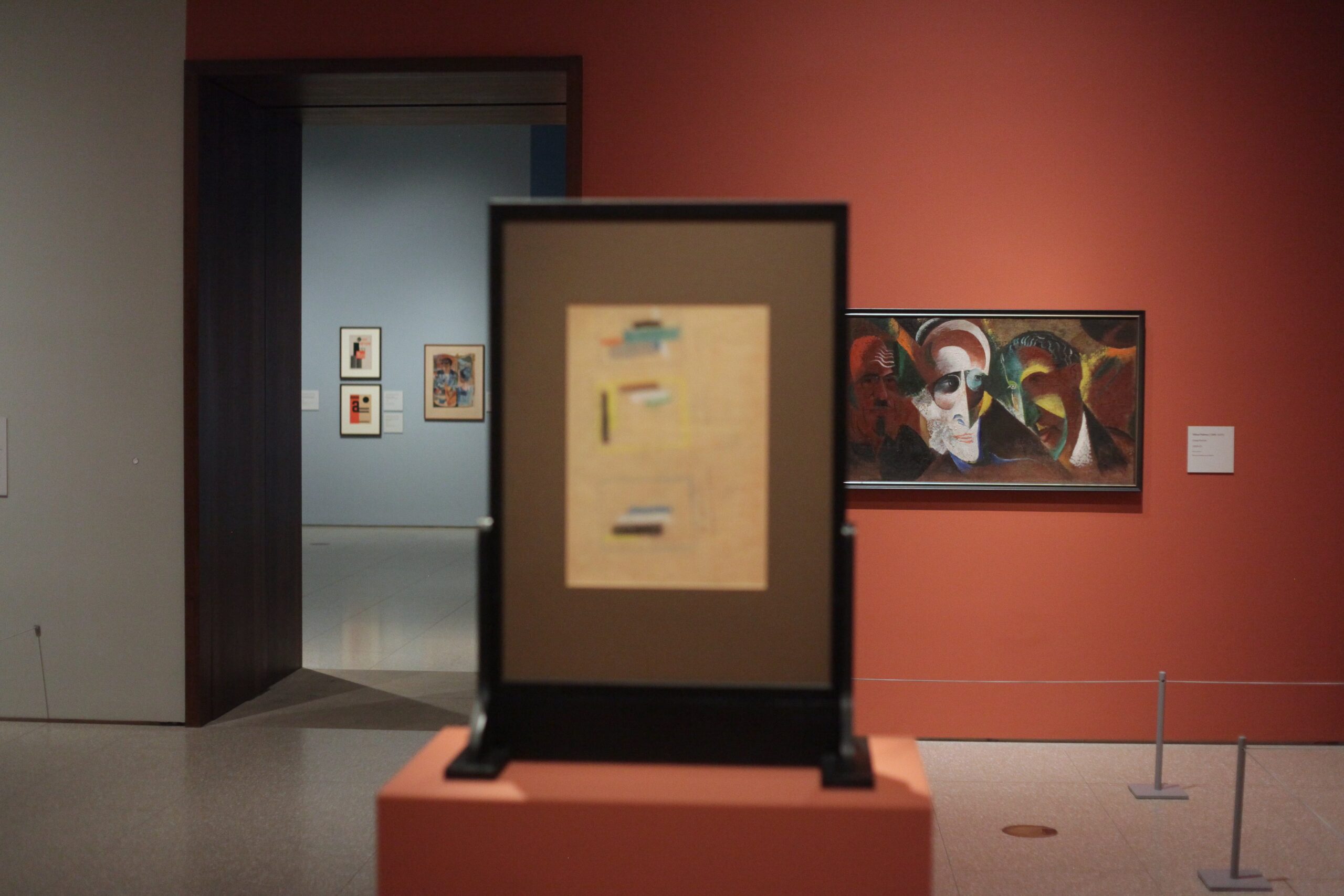

In Ukraine, modernism developed between the waning of one empire and the rise of another, after the crucible of World War I, as the nation struggled for self-determination. “In the Eye of the Storm”—the title of the exhibition at the Royal Academy dedicated to Ukrainian modernism—reflects the sentiments of that period, caught in historical turmoil. Yet, this period also witnessed an explosion of creativity, with ideas freely circulating throughout Europe. Alexandra Exter and Sonia Delaunay, both raised in Ukraine, were among the first to engage directly with Italian, German, and French avant-garde, pioneering experiments in rhythm and chromatic decomposition. Exter contributed to pivotal exhibitions at the dawn of modernism in Ukraine and Russia: ”Zveno,” “Tramway B,” and “0,10.” The latter, held in St. Petersburg and dubbed a “sensation of negative character” even by liberal critics, introduced the world to Malevich’s “Black Square,” a symbol of new consciousness. Kazymyr Malevich’s works of the later period, including a fresco sketch for the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences and the evocative “Landscape (Winter),” can be seen at the Royal Academy.

Sonia Delaunay’s “Simultaneous Contrasts” (1913), displayed in the exhibition’s opening hall, presents a world of semi-abstract vortices and geometric intersections. This work embodies the modernist ethos of distilling environmental essence through pure movement and color, transcending mere representation. Delaunay, in addition to her seamless integration into Parisian bohemian circles and her renown in haute couture, made history as the first female artist to be honored with a solo exhibition at the Louvre (1964).

Ukrainian modernism, while undeniably influenced by European trends, was fundamentally driven by a quest to unearth the essence of national artistry. This synthesis of national motifs and modernist techniques is exemplified in Volodymyr Burliuk’s avant-garde portrayal of a peasant woman, clad in traditional dress, with a massive Orthodox cross emerging from the collar. His use of blue-violet tones serves as an aesthetic homage to Kyiv’s ancient mosaics, bridging centuries of artistic heritage. Similarly, Oleksandr Bogomazov’s “Sharpening the Saws” (1927) employs a color palette clearly borrowed from traditional Ukrainian embroideries, ceramics, and carpets, transposing folkloric elements into an avant-garde visual language. This rich coloristic approach, distinct from both French cubism and German expressionism, emerges as a defining characteristic of Ukrainian modernism, which evolved concurrently with Western movements.

Alexander Archipenko stands as another pivotal figure in Ukrainian modernist history. By applying cubist principles to sculpture, Archipenko forged a unique artistic canon, somewhat resonant with Modigliani’s elongated forms. His elegant miniature bronze nude, a highlight of the exhibition, balances in precarious equilibrium, evoking the frozen motion of a spinning top. Archipenko’s international influence is highlighted by his participation in the seminal “Armory Show” in New York, his role in the “New Bauhaus,” and his design of the Ukrainian pavilion for the 1934 Chicago World’s Fair.

The exhibition “In the Eye of the Storm” of 65 pieces, evacuated from Kyiv in August 2022, may not unveil new horizons for the viewer—it underscores Ukraine’s integral role in the evolution of the global avant-garde. While some works may appear naive, controversial, or technically unrefined, they sing with chromatic expressiveness and evoke an emotional response. They embody an authentic passion for artistic exploration of techniques, ideas, and a new future. El Lissitzky’s contribution to “In the Eye of the Storm” offers a particularly striking vision of this new “bold” world, composed of metallic planes rent asunder by the lightning of change. Like refugees of art, these 65 exhibits journey from one European museum to another. Should the exhibition’s tour not be extended, London may become their final destination, a poignant parallel to the historical upheavals that shaped their creation.

Photo credit: IL Gurn

Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930s

29 June – 13 October 2024