The Unenviable “Bohemian Life”

In the heart of bohemian Paris, Irishman Schaunard composes a symphony titled “The Influence of Blue on Art,” Albanian Rodolfo finishes a painting in the art naïf style (for which he will earn one-tenth of what he spent on paints), and French playwright Marcel harangues publishers with his 21-act epic. Their bond is forged by friendship and voluntary poverty–a condition that, unfortunately in their case, is not the faithful companion of genius, but rather a consequence of their refusal to compromise the values imposed by society.

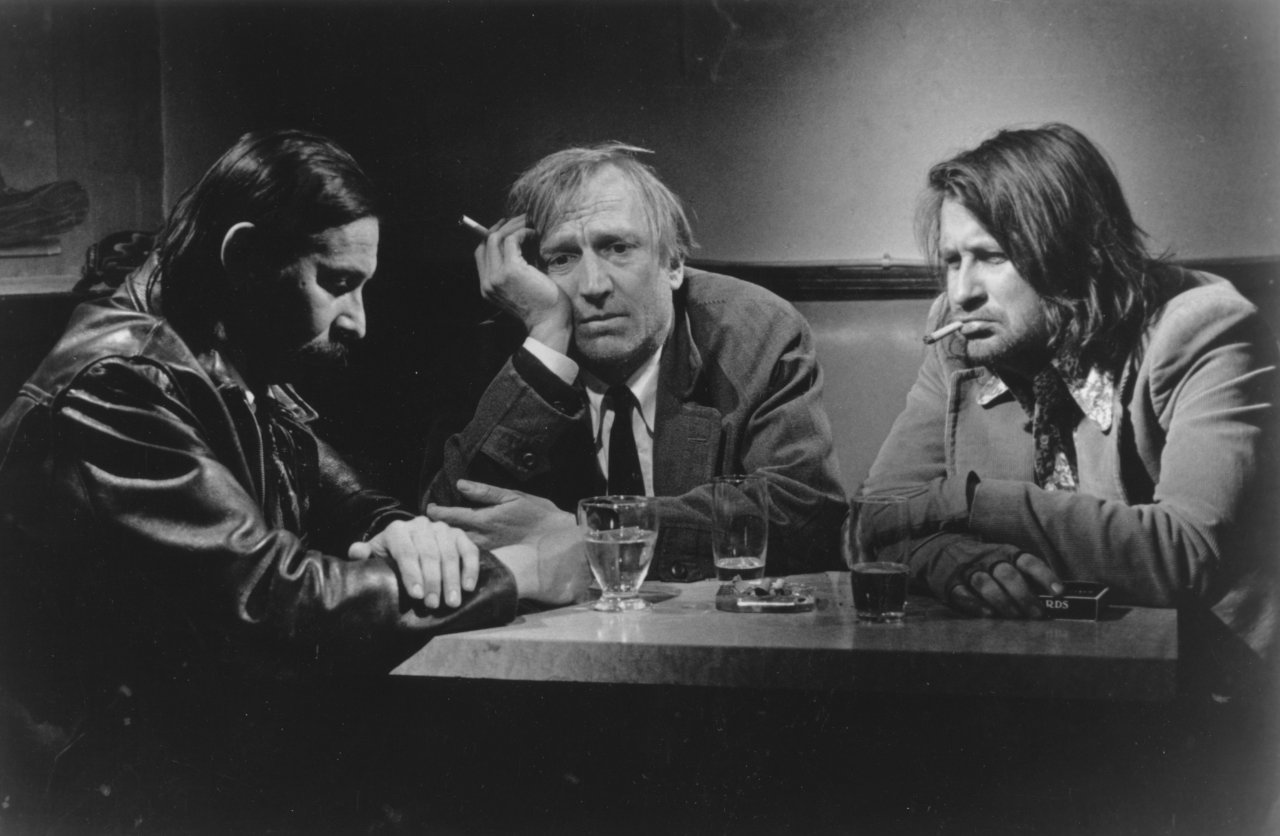

Following a series of programmatic work—“Shadows in Paradise,” “Ariel,” and “The Match Factory Girl”—that laid the foundations of hisdirectorial method, Finnish auteur Aki Kaurismäki makes his first cinematic foray into France. His characters, however, remain steadfast in their essence: lonely and alienated from the world, yet cognizant of how to indulge in the simple pleasures—a decent meal, gifts for their beloved—that sustain the soul.

“The Bohemian Life” can be classified as a comedy solely because its stoic artist-protagonists approach the ups and downs of the existential roller-coster with a creative spunk. For them, art is a method of survival, and survival is an art. The inherent romanticism of their being, tinged with melancholy, prevents them from completely losing touch with reality: when Rodolfo accidentally encounters Mimi at the threshold of his squalid apartment-cum-studio, he realizes that the world can no longer offer him anything more grand.

The commune of artist-ascetics leads a semi-impoverished existence, oscillating between moments of thoughtfulness and bouts of enlightenment, subsisting on potatoes and wine. This precarious balance seems disrupted whenMarcel is offered the position of editor-in-chief at the new women’s magazine “Iris Belt.” Flush with a paycheque, the first order of business is, of course, to visit a restaurant-cabaret, and the next day, with renewed energy, to enter a regime of strict economy.

Fortuna, capriciously commanding the servants of the muses, soon inflicts the first serious trial: Rodolfo, defenceless before the law, is deported back to his native Albania. AsBaudelaire, his forsaken dog, is taken in byMarcel and Schaunard, Mimi leaves for a wealthy admirer, the owner of a “normal” four-wheeled car (our heroes possess an “abnormal” three-wheeler). Yet, so be it: women come and go, money appears and vanishes—friendship endures, and the artists will continue to live from one stroke of luck to the next. Let’s smile once more, and Rodolfo, smuggled back to France in the trunk of a compact car, will be reunited with Mimi, for an artistic life on the verge of poverty alongside a stoic artist with a Maxim Gorky-style moustache is better than vapid comforts.

In the film, everything is so unstable, so fragile and fickle, that the secondary role of the sugar tycoon is played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, the “golden child” of the French New Wave, who has worked with Godard, Truffaut, and Kaurismäki himself. It is he, the messenger of Fortuna, who decides to become a patron, saving Rodolfo from seemingly hopeless situations thrice over. As an old-fashioned deity, Kaurismäki delights in subjecting his protagonists to hardships, only intervening when they, “having hungered,” are ready to despair completely. This sense of a watchful presence guiding their solitude allows the characters of the Finnish master’s storiesto precariously balance between existence and madness.

Unusually for Kaurismäki, “The Bohemian Life” is shot in black–and–white. This black–and–white is the first step into a world of borderline contrasts: bohemian Paris can be mundane and dreary, yet it is only there that one can join the brotherhood of the oppressed, find love, and perhaps achieve a semblance of success. Such a black-and-white cake, layered with despair and faint glimmers of hope, is meant to be savored with tears in one’s eyes, smile on one’s lips, and occasional laughter in the face of Fortuna.