Vasiliy Zorkii: “It’s vital to create new neural connections every day”

Vasiliy Zorkii is a musician, director, writer, producer and screenwriter, known for work at the intersection of music, theatre and text. He has led and participated in several musical projects, created theatre productions (Strana Moskva at TsIM; I’m 30 Years Old at the Gogol Centre), launched the international pandemic-era project Fairy Tales at Home, and written the novel The Biggest Bloody Ferris Wheel.

Photo: Valery Konkov/courtesy of The Arc Space.

Today, Zorkii is one of the co-founders of ARC Space in London — an independent interdisciplinary arts venue. ARC was conceived as an open space where people from different cultures, professions and generations can meet, talk, collaborate and create joint projects: from exhibitions and discussions to new theatrical formats. ARC’s February programme is vast and varied.

How much time and energy did it take to put together such a programme?

We properly started working on the project in October, and the number of events has been growing exponentially. How much energy it’s taken, I honestly don’t know. The headteacher at my school used to say: don’t count the steps as you’re climbing to heaven.

Originally there were three of us: Misha Tomshinsky, who owns the space, his wife Vera, and me. For each of us the project is about something different — which is even more interesting. For me personally, it’s a way to reinvent myself. When the war began in 2022, I thought: if even this doesn’t force us to change inwardly, then nothing ever will. It’s one of those points in history when it’s time to think about an enormous number of things — how we live, how we’re put together, how we want to live, what sort of people we are.

And it feels like we’re in a moment when we should be asking: what kind of world are we building? How are we building it? What values unite us? I wanted there to be a place that becomes a meeting point for very different people, grounded in shared human values. On the one hand, it was important to create a space where people with similar humanist views could meet — people who believe you can remain open to the world; who believe war is wrong; who believe light wins over darkness; that a person can be more than they think they are; that loneliness is, in a sense, a choice. And who believe that sometimes you simply need to walk up to someone and say, “Hi — fancy a chat?”

So it’s a place where, in a sense, ‘your own’ people gather?

Absolutely not. It mattered to me, yes, to bring together people who feel close to us. But you can’t turn something like this into a preserved bubble. Communities are very often formed through exclusion — especially in London: old money, Oxford. We’re saying the opposite: you can join our community. It brings together younger and older people, English people with anyone at all, Poles with Russians — on the basis of shared human values.

For Misha, by the way, it was also important that ARC should be a meeting point between the IT universe and the humanities/creative world. There’s a sense an artificial divide has been created — largely by people in the humanities, frankly. I worked for many years at Afisha. I love Afisha, but it had this rather snobbish principle: if you don’t understand something, you’re a bit of an idiot. “It’ll be as we say,” was practically the slogan. On the one hand, it was charming. On the other, it was humiliating — separating.

Фото: Valery Konkov/courtesy of The Arc Space.

There are always two ways to explain something. One: if you don’t get it, you’re thick. Two: come on, I’ll show you — it’s genuinely fascinating. I think the second way is better.

Our place is devoted to the creative process. It’s independent, it doesn’t belong to any institution, and we bring together very different personalities — people with experience and people without. For instance, we currently have an exhibition by Roma Liberov, Reflections: “A Poem Is as Real as a Utility Bill”. Roma’s work is precisely about exploring one’s relationship with the city.

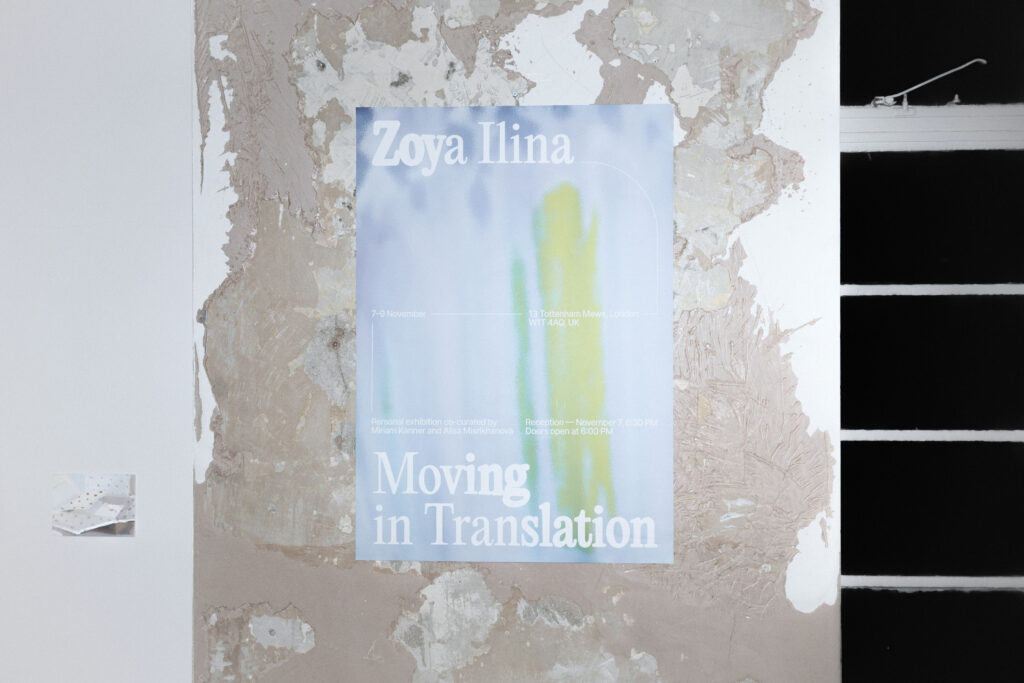

It matters hugely to us that the curator of this exhibition is a UCL student, Miriam Kanner — because she came in, looked at Roma’s work, then connected it to another of his projects and suddenly there was extra depth, a fresh perspective. In other words, we give young people the chance to try things — and that’s where life is. The very first exhibition we did — by the artist Zoya Ilyina — was also about that: the curators were Miriam and Alisa Misrikhanova from Parsons. I think that if we want to live in a new world, it’s vital to create new neural connections every day.

We had an event the other day called Serving the People: creatives from different countries meet and talk about how they live. One evening an American, a Canadian, a German, a Chinese woman and an Englishman were discussing the Second World War. The American says, “We won you the war.” I say, “Hang on — there’s a nuance.” And then the girl from China says, “Listen, fifteen million Chinese people died in that war!” — and practically no one in the room knew it… It was an incredibly important conversation.

So it’s a place where people from different cultures meet, look at one another, learn?

Of course. Russian culture is very used to operating in this mode: “Sit down, I’m going to tell you about myself — how I suffer, how awful I feel. But I’m not going to do anything about it. You’ll feel sorry for me, and you won’t be able to help anyway.” And then it turns out that when you give space to another person, they can talk to you. They can tell you how they feel, what they think about you. That dialogue is essential. Since the war began, it has become even more essential, I think.

Photo: Anna Dmitrieva/courtesy of The Arc Space.

I want to do an event where Boris Grebenshchikov and Thom Yorke listen to each other’s songs in a room with fifty people — and we won’t even sell tickets.

Well that’s elitism, isn’t it. Here it comes.

No, no. No elitism. First come, first served — whoever gets there first gets the slippers. I don’t yet know how to do it. But I think we’re far too blinkered about what can and can’t happen. We walk through these endless tunnels of the same events — events we ourselves have been bored of for twenty years, but we don’t know any others.

So let’s do an evening of bad dancing. Let’s play an imaginary circus. Let’s do history classes at Year 7 level, because it turns out I — and many of my friends — don’t know any of it. We were just embarrassed to admit it our whole lives. Or let’s have major artists reading fairy tales to children and adults, like we did before.

I remember that. During Covid, it was called Fairy Tales at Home, wasn’t it?

Milla Jovovich rang me in the middle of the night and said, “Can I read Mukha-Tsokotukha in Russian for you?” I literally fell off my chair at home. The truth is there are no limits — it only depends on us.

Photo: Anna Dmitrieva/courtesy of The Arc Space.

I grew up in that very brief moment when Moscow really did feel like the cultural centre of the country. Bands that now fill stadiums would come and play in tiny Moscow clubs. It was an exciting place. It was a time of great freedom. I want to experience that again — but on new value-based terms. Yes, it was brilliant then, but we didn’t think enough about the values from which we were speaking to one another.

But everyone was young and happy.

I’m not blaming anyone. But I think we — I personally — bear a certain responsibility. Even then we could have thought: democracy matters. An independent judiciary matters. It matters that police officers don’t torture people in prisons. But we were having so much fun that we missed it all.

Now we have a unique opportunity to apply our talents where there is ground for it.

And the second thing: the Soviet system taught us that we have our own special path and the West doesn’t need us. That’s utter rubbish. There are things we can do brilliantly — we just need to stop being ashamed of it. Our experience doesn’t have to be thrown into the fire simply because we now live somewhere else.

Photo: Anna Dmitrieva/courtesy of The Arc Space.

So anyone can come to you and say, “Vasiliy, I have a project”?

That’s exactly what happens. But we now want to assemble some kind of board — people whose taste we trust — so it isn’t a personal decision.

Once, I was the creative director of Strelka in Moscow, and I tried to turn Strelka into an interdisciplinary discussion space — where gallery owners could gather and talk about their business, or sixteen designers could argue about the future of the profession. I’m for discussing all sorts of questions.

Yes, anyone can come to us and say, “I’ve got a project.” Then we have to work out whether we can carry it — we’re a small place — and whether it fits our value system. And then, yes: we do it.

For example, on 13 March we’re opening an exhibition by Dima Pantyushin. He’s a major poster artist who still doesn’t fully grasp the scale of his own talent. He did a huge amount for Russia’s cultural scene in the 2010s: Solyanka, Enthusiast, TOTO, Krugly Shar, New Holland. As a poster designer he built an astonishing bridge between Rodchenko and the Soviet poster tradition, combining it with Eastern European and Italian poster styles. No one has really processed just how important a cultural figure he is.

Photo: Anna Dmitrieva/courtesy of The Arc Space.

You talk about dialogue. In February you’re hosting a performance in the form of a conversation — Night Conversation.

It’s a film script I wrote in 2021, before the war began. Two people — a Moscow actress and an events professional — end up in the kitchen of a woman who’s been living in Berlin for twenty years. And they start talking about basic, life-defining things.

Those two see themselves as very liberal, but it turns out that no matter what they start discussing with the Berlin woman, there’s a chasm between them. They talk about everything. Is it acceptable to hit children? Can you wear Hugo Boss if Hugo Boss produced Nazi uniforms? Is it acceptable to laugh at disabled people? They begin arguing, and through that argument a much larger story unfolds — the context of each person’s life, and a deep layer of serious, lived pain.

Here at ARC we’ll do a reading in which the audience will find themselves inside the film. Three performers — me, Alisa Khazanova and Maria Bolshova — act out the script while a camera operator simultaneously brings it up on screen. You can watch it as theatre, or you can watch it as a finished piece of cinema.

In a sense it’s a performance about the causes of the war — about what was washed away in an instant on the morning of 24 February. I don’t know what was in the head of someone working at a factory in Vladivostok. But I do know what was in mine — a liberal Moscow intellectual with a decent salary, living in the centre, attending events, sitting at the same table with, say, Kirill Serebrennikov, Ksenia Sobchak, Anton Krasovsky and Vyacheslav Volodin. We all greeted each other, shook hands.

Now I’m trying to understand my own measure of responsibility. Obviously I didn’t start the war — but as a public figure I do carry some degree of responsibility. It’s a difficult ethical question.

We’re going to host debates — a British initiative, by the way — on whether people should be held responsible for the actions of their country. Are the British responsible for the Arab–Palestinian and Israeli conflict? Are Americans responsible for Iraq, Iran, Syria, Libya and the rest? And Russians — are we responsible? And if Palestinians aren’t responsible for Hamas, then why are Russians’ bank cards blocked?

Do you want to talk about that in Britain in 2026? It’s a nuclear conversation — but a good one, an important one, and a very difficult one. The kind of conversation it’s actually great to have — without being afraid.

That was going to be my question — about “not being afraid”…

We’ve already been afraid. That’s enough. We left a country where you had to be afraid of everything. Perhaps we’ve ended up in a similar situation partly because of social media: the ability to talk to another person without assuming they’re an idiot has disappeared.

We’re so polarised that any view that doesn’t match ours is dismissed. It’s a propaganda tactic: the world is so complicated that we won’t even discuss it. But discussion is exactly where our conversation begins.

We recently did a project like this: we took one song, translated it into eight languages, recorded it in eight different countries with eight different musicians. It was fascinating how changing the language shifted the mood and the meaning. It’s a huge research field: how do we learn to speak to each other?

I always felt that musicians are, by nature, people who reject war. Did you lose friends, close people, when you left — when you saw that your views didn’t align?

The whole idea of asking musicians or actors what they think about life seems slightly misguided to me. If not downright presumptuous. Most musicians I know — and actors too, with rare exceptions — are absorbed in their craft. To talk about life, you need to live life. If you spend four years in a theatre from morning to night, then read books until six in the morning, you don’t become a great thinker — you remain an artist.

That doesn’t mean artists are stupid. But asking any artist what they think about life seems incorrect. Yet for some reason we endlessly watch interviews with Actors, Musicians, Artists. Let’s ask people whose job is to think. Artists won’t explain how to live. And perhaps it’s time to stop asking everyone altogether — and think for ourselves.

I had a great experience in Cannes in May last year. There was a Robert De Niro masterclass, and people kept asking him: how did we get to what’s happening in the world? And he kept answering the same thing: “I don’t know — I’m an actor! Ask me how I act. As for life, any thoughts I have aren’t worth more than yours.”

I think the division between those who left and those who stayed is artificial. It’s important to say that there’s some huge merit in the fact I left. I’m simply privileged — I was lucky, I had the opportunity. Some people don’t.

I divide people more by views. In that Moscow frenzy — when everything was great, there was money — we simply didn’t discuss certain topics. And now I’ve suddenly realised: there are vast numbers of people, musicians especially, who passionately support what’s happening — and that was an enormous disappointment. There are those who are frightened — and you can understand them.

Only when I left Russia did I start understanding how traumatic certain things actually were: the fear of being arrested, the fear of unaccountable power. You never know — if you’re thrown into a cell, what they’ll do to you there.

Photo: Valery Konkov/courtesy of The Arc Space.

I lost many friends because of the war in Ukraine, but oddly enough I’ve fallen out with far more people because of Israel. When I read posts by my right-wing friends, I want to shoot myself; when I read posts by my left-wing friends, I want to shoot myself. It feels like everyone’s lost the plot. It’s probably made me more centrist, because both sides scare me equally.

And what I want to do at ARC is connected to common sense: let’s talk. We’re adults. We can moderate emotions — our own and other people’s.

But who’s going to moderate those conversations? They’re very ‘nuclear’, as you said.

When the war in Ukraine began, many people said: why try to talk to Ukrainians now — they won’t hear us, they won’t understand us. I replied: I want to.

At the same time it’s strange, when you meet someone whose home a rocket has hit, to say: I’m so sad, I hurt for you, I can’t sleep, I’m suffering. It doesn’t make them warmer or colder — they no longer have a home. But if you say: how are you, tell me what’s happening to you — you discover that for many people from Ukraine it was incredibly important that someone born in Russia understood how they were doing.

Photo: Valery Konkov/courtesy of The Arc Space.

Sometimes pain, rage, anger boil over — but then you build unbelievably strong relationships. Over four years of war I’ve made more friends from Belarus, Ukraine and other countries shaped by the Soviet past than from my own country. Because you need to be able to listen, to feel another person’s pain and be ready for it.

At the same time you don’t have to burn your passport and pretend you weren’t born in Russia — on the contrary.

I was recently in Paris with the Canadian musician Patrick Watson, and we spent two hours talking about why Russian music never became popular internationally, why it didn’t break out of its local bubble. And he said, “You Russians have one problem: you don’t lean on your own heritage. Instead of listening to your Stravinsky and Shostakovich, you keep trying to make English music — and English music, in turn, takes everything from Stravinsky and Shostakovich… like your beloved Radiohead.”

That really interests me. Why is Céline Dion’s All By Myself essentially Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto, and I don’t have a song like that? Why don’t we use this? Why do we know nothing about our own folk songs?

Photo: Valery Konkov/courtesy of The Arc Space.

Let’s explore that intersection — that seam, that place where things are glued together. And try to reassemble it in our heads: understand what matters, what doesn’t, what to keep — and what to say goodbye to forever.

We started with Roman Liberov’s exhibition about the relationship with the city. What is your relationship with London?

There’s a brilliant video where Sir Ian McKellen explains why he loves Manchester: because taxi drivers there say, “Hello, love — how are you, love?” and he feels at home.

The first time I came to England was at Christmas. Everyone was in festive jumpers at the airport, singing songs. I remember thinking: this is a good city.

In general, everything important in life — at least in my life — begins with love. It just happened, and I felt I was in the right place. And there’s also a powerful feeling when you realise that all the quotations, all the films, the books, the music — they’re here, on the streets next to yours.

I once spoke about this with Boris Borisovich Grebenshchikov, and he said that when he first came to London in the 1980s he also felt it was his place.

People often ask me what creativity is — I don’t like the word very much — but I think it’s a mix of a few things: genuine curiosity and love of life; the desire to keep learning; the desire to share what you learn; and the ability to play — not in the sense that “life is a game”, but in the sense that you can make the world around you a little more unusual and interesting. I think it’s an important feeling, one you have to protect in yourself.