Stuart Lawson: “Dancers communicate through movement, not words!”

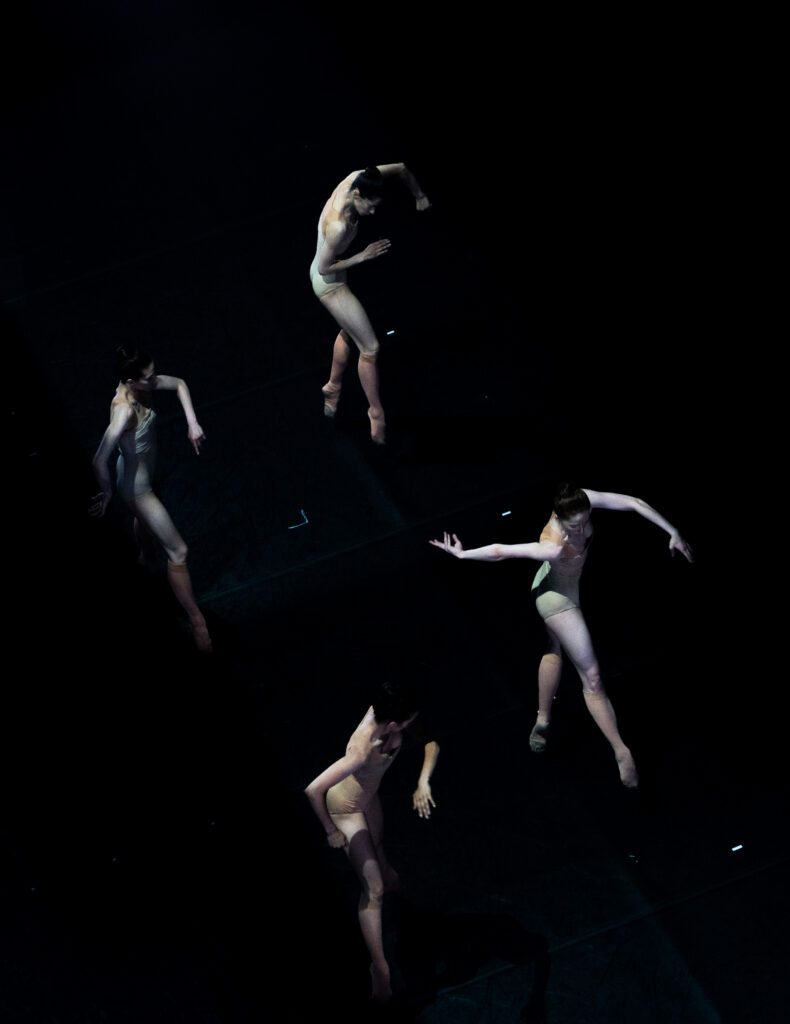

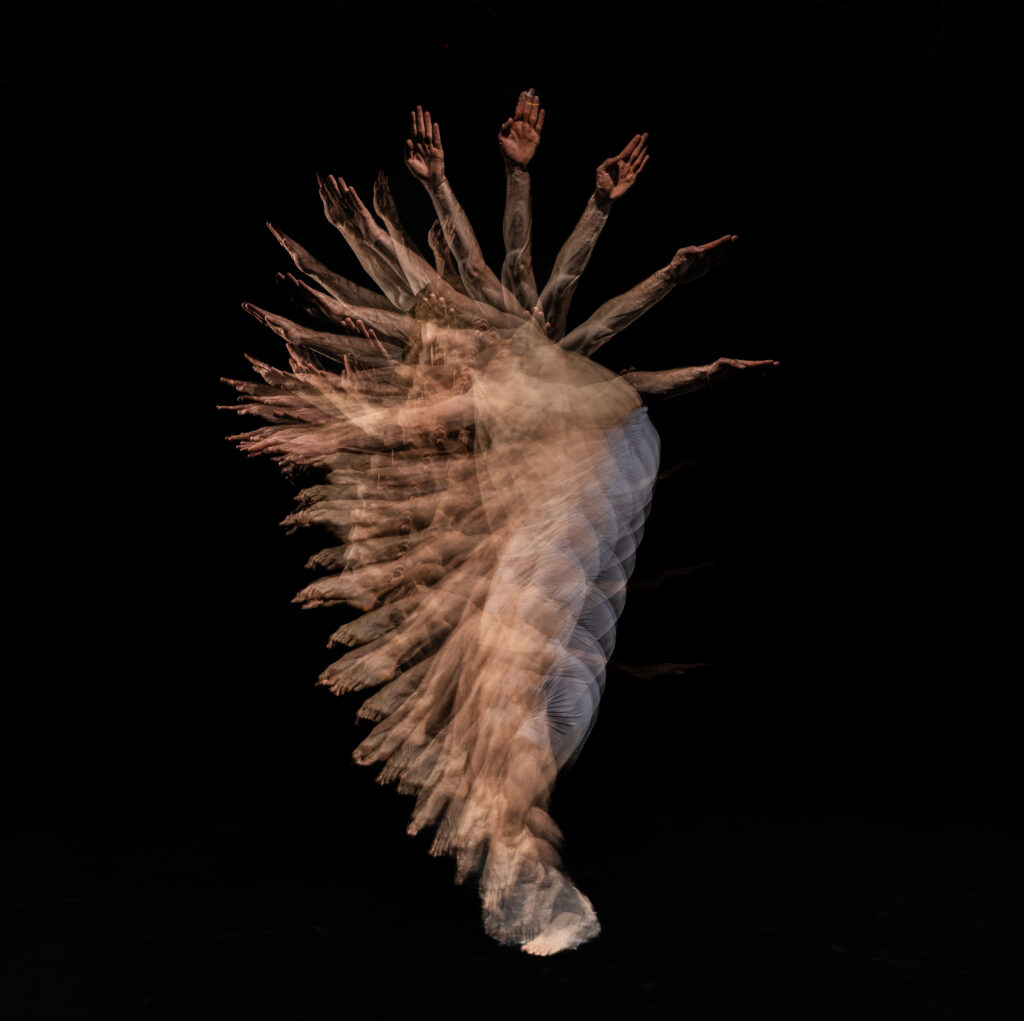

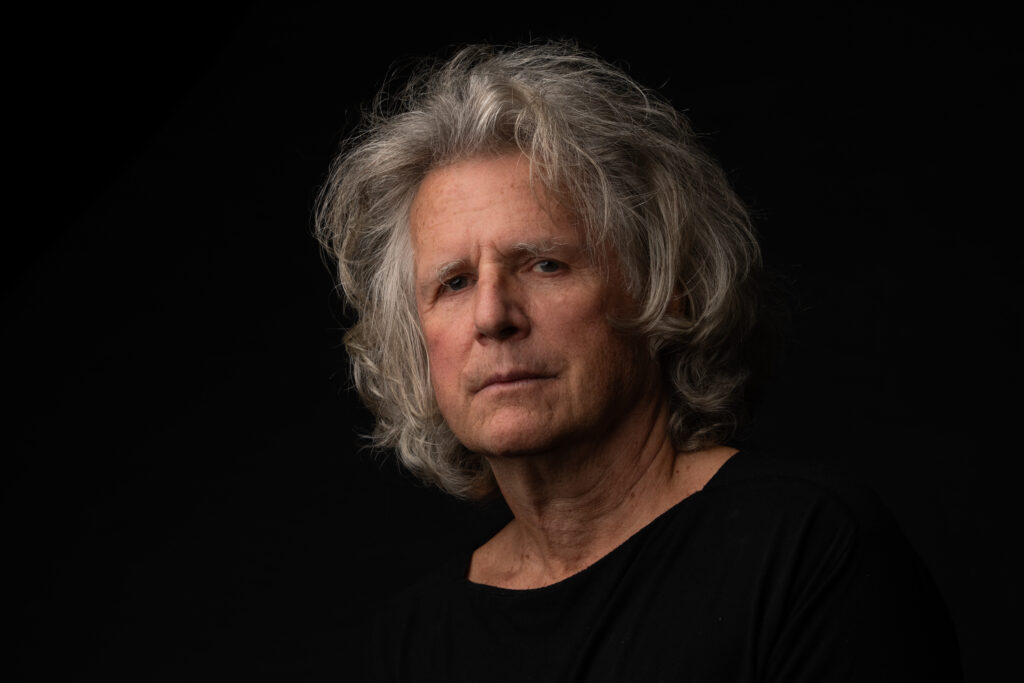

British photographer Stuart Lawson, the author of distinctive visual narratives about movement, memory, and identity, has long worked at the intersection of photography, choreography, and human character. His signature technique of chronographic portraiture – where gestures multiplied by the lens intertwine with the dancer’s inner states – reveals not a frozen second, but a metamorphosis of human experience. In January 2026, a new exhibition, “Metamorphoses”, took place in London at the gallery space St John’s Waterloo, presenting Lawson’s works that reflect his long artistic journey – from documentary stories captured on the ballet stages of Russia to portraits of craftsmen and musicians from different parts of the world. In this interview, Stuart speaks about why the language of the body is so essential to portraying the human being, and how photography helps us understand what words are sometimes unable to express.

You spent a lot of time in Russia…

I first came in 1995 and stayed. It was a fantastic time. And then, of course, everything that followed was wonderful too.

I also spoke with violinist Roman Mints – he told me the story. It really does sound like destiny – what your meeting in Moscow and working together led to.

Yes, absolutely. Roman even wrote a lovely post about how much he appreciated what I did 25 or 30 years ago.

In essence, you significantly helped the festival at that time, didn’t you? And many other initiatives as well.

Yes, that’s true. I was very closely connected with the school Roman graduated from – the Gnesin School. I knew Mikhail Hokhlov, who was the headmaster at the time. When I was working in banking, I was always looking for ways to bring culture into the institution – music, visual art, and other forms of creativity. I also collaborated with students from the Surikov School. When I bought a building for Citibank, I invited students to exhibit their paintings there. Years later – probably 12 years later – one of those students came into my office at HSBC and said: “Because you did that, we’ve been able to build the largest collection of Soviet realism in America.” That really struck me. You do something small, you lose sight of it – and then many years later it comes back, and you realise how important it was.

I’d like to ask you about identity. In the preface to your exhibition, you talked about how your work explores identity. What does it mean for you?

– Let me take a step back. My entire worldview was shaped by the fact that from the age of 23 I lived in other people’s countries. I’m British, I grew up in London. My father was an immigrant from South Africa, originally from Lithuania. He was Jewish; his family left Lithuania for Cape Town, then Johannesburg. Later he moved to Scotland and became a doctor, and then practised in London. So, in a way, my roots are Lithuanian – though I’ve never really explored them consciously. They’re just part of my DNA. I joined Citibank when I was 21, in London, and then I started moving. Over 25 years with the bank, I lived — not visited, but lived – in 11 countries: England, Scotland, Kenya, Greece, Egypt, France, Norway, Italy, Russia, Puerto Rico, and the United States. In every country I tried to connect with local people. I didn’t mix with expatriates – I wanted to understand the culture from inside. As a result, my son from my first marriage is American. He grew up in Sag Harbor, in the Hamptons. But because I was living in Russia, and because I promised to take him to every country I lived in, he became a global citizen. Today he’s a videographer. He was just in Saudi Arabia, and as we speak he’s flying to San Francisco. He inherited from me – and I inherited from my father – a love of the world and a deep curiosity about other cultures.

Is it important where a dancer was born – Russia, France, somewhere else? Can you sense it in the way they move?

Absolutely not. One of my close friends is Anna Turazashvili from the Bolshoi theatre – she’s Georgian, a soloist, a wonderful dancer and person. I was in Perm when they invited five Brazilian dancers from São Paulo to join the company. They stayed for several years. They didn’t speak Russian – but everyone understands French ballet terminology. That was the common language. What fascinated me was that dancers communicate through movement, not words. Their communication is not verbal, not cultural – it’s physical. If anything, I see more difference between classical and contemporary dance cultures than between national backgrounds.

How did ballet enter your life?

It began with one weekend in Perm, Russia. I was invited there to give a lecture – I’m an honorary professor at Plekhanov University and several others. After the lecture, they took me to the Perm Ballet. I didn’t realise then that it was a descendant of the Kirov Ballet, relocated during World War II, carrying with it the DNA of excellence. I had no particular interest in ballet at the time. Ballet didn’t attract me – ballet appeared. What changed everything was access. That weekend – February 14, 2015, incidentally the same weekend I met my wife, who is from Perm – I watched the ballet, and from that moment on I returned every six weeks. I would lecture, and then spend two or three days inside the ballet, ten hours a day. I’d been a photographer since the age of ten, but that experience gave me the impetus to move forward seriously with my photography.

Is the language of the body important for you as a photographer? How did you learn to read and understand it?

I had no background in dance. Before Perm, I went to the ballet maybe once every six months. But during that intense period, I spent hours simply observing. Sometimes I wouldn’t even take photographs – I’d just sit and watch. Over time, I began to understand the rhythm of that world: not musical rhythm, but the rhythm of repetition, correction, daily progress. Watching a dancer work one-on-one with a teacher was especially revealing. A movement would look perfect to me – but the instructor would say, “No, this is wrong,” and demonstrate a tiny adjustment. At first, I couldn’t see the difference at all. But what resonated with me was the philosophy behind it. At the time, I was teaching a course on “successful failure” – the idea that progress comes through failure, not success. I even used ballet lessons as an example in leadership training. I showed managers how dancers accept correction openly, repeat the movement, and improve – without ego.

How do you think – do dancers have a special inner fire? Federico García Lorca called this state “duende”. Is it something unique to dancers, or does it belong to everyone who is connected to art in one way or another?

Let’s focus on dancers. Look at their lives. A professional dancer works six days a week, eleven months a year. Their day starts at 11 a.m. and ends at 11 p.m. That’s twelve hours in the theatre. Out of a hundred students, five succeed. Every year, at least 30% are cut. You start at seven years old and maybe – maybe – by 17 or 18 you enter the corps de ballet. From there, you fight to be noticed, to become a soloist. It’s a long, hard, unpredictable road. Without passion, survival is impossible. And they don’t earn much money – certainly not enough to justify the effort without love. That’s why I called one of my exhibitions Dancer’s Soul. That passion is what keeps them going through endless hours of practice.

When I look at your photographs, I almost hear music. Is music important to you?

Very important. Always has been. I’ve photographed musicians – percussionists, conductors, orchestras. One of the tattooed musicians you saw is Alexander Tsoi, Viktor Tsoi’s son, from Kino. A close friend of mine in Russia is Ilya Lagutenko from Mumiy Troll” – we’ve known each other since 2004. I’ve been to 40 or 50 of his concerts. But if you ask me about favourites – it’s classical ballet: “Swan Lake”, “Giselle”, “Sleeping Beauty”. The moment the prelude starts, before the curtain rises, I get goosebumps. That tension – it never leaves me.

Can you tell us about your technique?

My documentary work uses available light. But my constructed images require a completely dark studio. Light is everything in photography – it’s the medium itself. Movement comes from constant light; multiple images come from strobe. Some images combine both. One thing is essential to say: no AI, no artificial post-production. I adjust exposure and colour, but I never add anything. What you see is what the camera captured. For every image you see, there are dozens that didn’t work. But these successful shots require dancers at the peak of their art. That’s what made Russia extraordinary for me: access to phenomenal talent.

How do you build connections when you work with dancers?

At first, in Perm, I didn’t interact at all – I simply documented. Later, when I began creating images, communication became essential. I can’t demonstrate movement physically, of course. Instead, I describe the image, the idea. The dancer performs, I show them the photograph immediately, and together we refine it. It’s a dialogue – visual, not verbal. Some images are unrepeatable because they demand perfect balance and control. Only the very finest dancers can do that. And that, for me, is the beauty of it.

What advice would you give to people moving to a new country?

Learn where you are – not just geographically, but culturally and historically. Respect the place before you arrive. Too often expatriates carry only their own culture. But if you’re entering someone else’s world, openness is essential. When I moved from Moscow to southern France, I was unhappy at first. My wife told me: “You can’t leave your camera in the corner.” So I spent a month photographing 60 shopkeepers in our medieval town. That project later became an exhibition in Tashkent, supported by the French Embassy. Integration comes through curiosity, language, and genuine interest in people.

You must be logged in to post a comment.