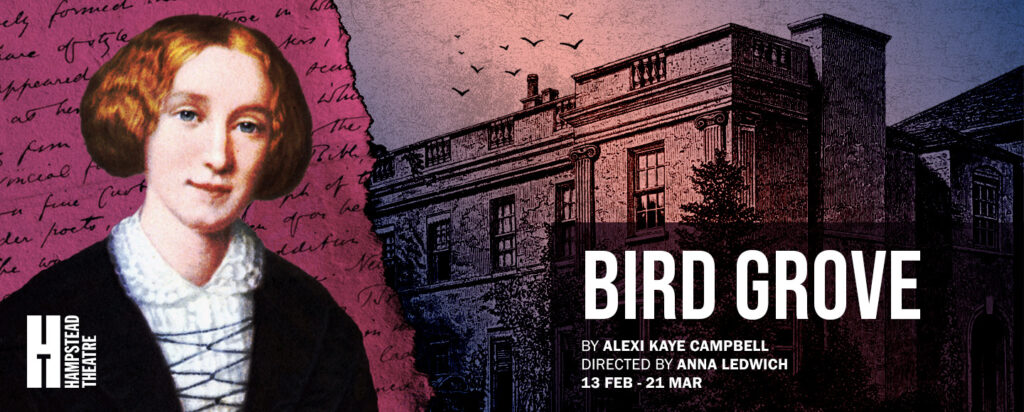

Loyalty Costs a Life: The premiere of Alexi Kaye Campbell’s Bird Grove has opened at Hampstead Theatre

This is a play about the making of the famous George Eliot — or rather about the days when Eliot did not yet exist, when there was only Mary Ann Evans: daughter, sister, passionate soul, prodigious talent. As in any biographical drama rather than strict documentary analysis, there are liberties taken — temporal and psychological alike. Yet these liberties elevate the play from the private story of a celebrated writer to a poetic meditation on duty, love, and vocation.

Under Anna Ledwich’s assured direction, this reminiscence structure comes fully into its own, allowing memory to bend time and reshape biography into something fluid, intimate and theatrically immediate.

First and foremost, Bird Grove is a work of striking beauty. The arcs of its characters are built from heavy, solid brick, yet the story that spans the play from beginning to end — like a bridge — appears delicate, precise, almost lace-like. Not a single superfluous line, not a single redundant scene. The entire action unfolds within Sarah Beaton’s set design.

Plum. Everything is plum. A rich, aristocratic, unmistakably Victorian shade — from deep mahogany to the dark blush of ripe fruit. The ladies’ gowns, the gentlemen’s frock coats, the upholstery, even the large enamel teapot — all bear the mark of cultivated respectability. Yet this very respectability carries unease. The colour of bruising, of dried blood, of grief and confinement — a widow’s violet.

When Richard appears on stage (a magnificent performance by Owen Teale) — what power, what charisma! — his voice fills the house like a tide, claiming every corner. A restrained lion’s roar. Master and sovereign. His son bends to help him with his tall boots.

Father and son discuss her — Mary Ann. United by an instinctive sense of family authority, they speak of her almost tenderly.

And then she enters (Elizabeth Dulau as Mary Ann) — or rather, she is swept in by wind. The hem of her dress trembles, the heart-shaped coiffure refuses to loosen, her hand rests upon her tightly cinched waist as if she has inhaled and forgotten how to exhale, heels clicking across the parquet. Her face — pale, fine, with silk-thread brows — resembles a lily. Who would dare call such a living, trembling face unattractive?

Only those closest to her — her father and brother.

Why? Fear she might grow vain? Jealousy? Or perhaps — and this seems truer — they see in her only a resource: support, assistant, debtor. A willing beast of burden, bearing her dark woollen cross, never asking to be paid.

Layer by layer, the play reveals how the space around Mary Ann grows tighter.

In families where loyalty to the system is the highest virtue, a person’s worth is measured by obedience. The logic is crystalline: comply and you are good; desire something of your own and you are strange, wrong — almost criminal. To resist such logic is difficult, especially for a daughter, especially the younger one, and especially for this emotionally attuned child of a widowed father.

Yet the sponsor of Mary Ann’s iron will is a dream — or, if you prefer, a calling. It pulls her forward like a hound straining at its leash. Blessed is the person who has a vocation — literature. The bookcases stand like the columns of St Mark and St Theodore, guardians and pillars of the house, especially for Mary Ann. How does one choose between loyalty and a calling?

Richard — proud lion’s head, commanding stride. And — oh God — he dismisses his daughter’s comical suitor not because the man is ridiculous, but because Richard himself needs Mary Ann. Obedient, cheerful, loving, attentive. Sharing his hopes, his views, his interests. Dreams? Certainly — but only those dreams sanctioned by the parent.

Otherwise the punishment is swift: shouting, tragic tears, manipulations of health, papers flying through the study like startled gulls.

He loves her deeply. And he suffers when Mary leaves Bird Grove. But what he mourns is not the new woman she is becoming. He mourns the old one — the compliant daughter seated at the boot’s edge, always ready to console the grieving widower.

The play unfolds as a space of Mary Ann’s memory — a reminiscence structure. Through her eyes we see her father and her brother Isaac (Jolyon Coy), elegant, sharp, emotionally glacial. His politeness wounds more deeply than open rudeness.

Then there is Mr Garfield, the suitor introduced by Isaac — distilled comedy in every gesture. Jonnie Broadbent performs him with exquisite seriousness, as though occasionally checking whether he is sufficiently pompous and dreadful. Inevitably, one recalls Mr Collins from Jane Austen — but this is homage, not imitation. The play abounds in such echoes. Richard himself feels like a composite father of English literature — something of Lear, something of Soames Forsyte.

Historical figures are poetically transformed through Mary Ann’s imagination — and she, in turn, is shaped by Campbell. The Brays (Tom Espiner and Rebecca Scroggs), Mary Ann’s friends, appear almost as emanations of her intellect. Must there not be people who support her? She seems to appoint them, in thought, as her ideal parents. And Maria (Sarah Woodward) — teacher, nanny, warm friend — even she ultimately sides with the system, urging Mary Ann to renounce her dreams. Sacrifice is nobler than happiness, after all — and happiness has never truly belonged to Mary Ann.

She loves her father. She gives him seven more years.

Gradually the meticulously arranged furniture seems to swell with the air of attachment; the house itself becomes another character. And the impending collapse becomes inevitable — for Mary Ann, though not for George Eliot. The collapse must happen.

The table stands empty. The parquet gleams. The hearth darkens. Everything is taken from her — not only by the draconian laws of entail (though they play their part), but by a system that never fully took a younger daughter seriously. Everything but the dream. Everything but the calling.

Two hours by train from the theatre, in Coventry, Bird Grove still stands — dark, quiet, its worn walls holding little more than memory, which now resembles a ghost. Enthusiasts hope to restore the house, to create a George Eliot museum. But for now, it is empty.

“If a phantom had once, in fact, resided in this place, he’s certainly abandoned it. Abandoned”.